The “polar vortex” is synonymous with cold air blasts for Americans. But is it correct to equate polar air with the polar vortex? The answer is no.

Lake Michigan and Chicago during the Polar Vortex event of January 2014. Photo: Edward Stojakovik

Recently, former meteorology classmates of mine complained about how the media and general public were conflating cold waves with the polar vortex. From my experience as a student, I have to concur. We learned about the polar vortex from synoptic maps where a low pressure system tended to be stationary over northern Canada.

Polar vortex and cold waves

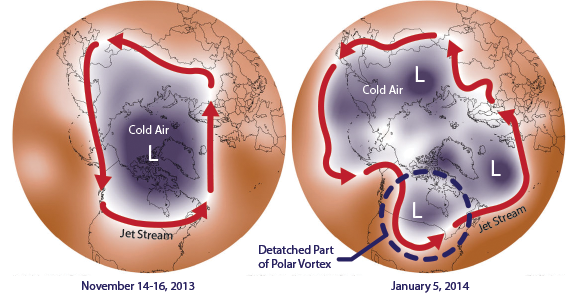

Areas in the mid-latitudes are prone to cold outbreaks during the winter months due to meanders in the jet stream. Although sometimes pieces of the polar vortex—low pressure systems that slide south from the arctic region—do affect the lower 48, this isn’t always the cause of cold air out your door.

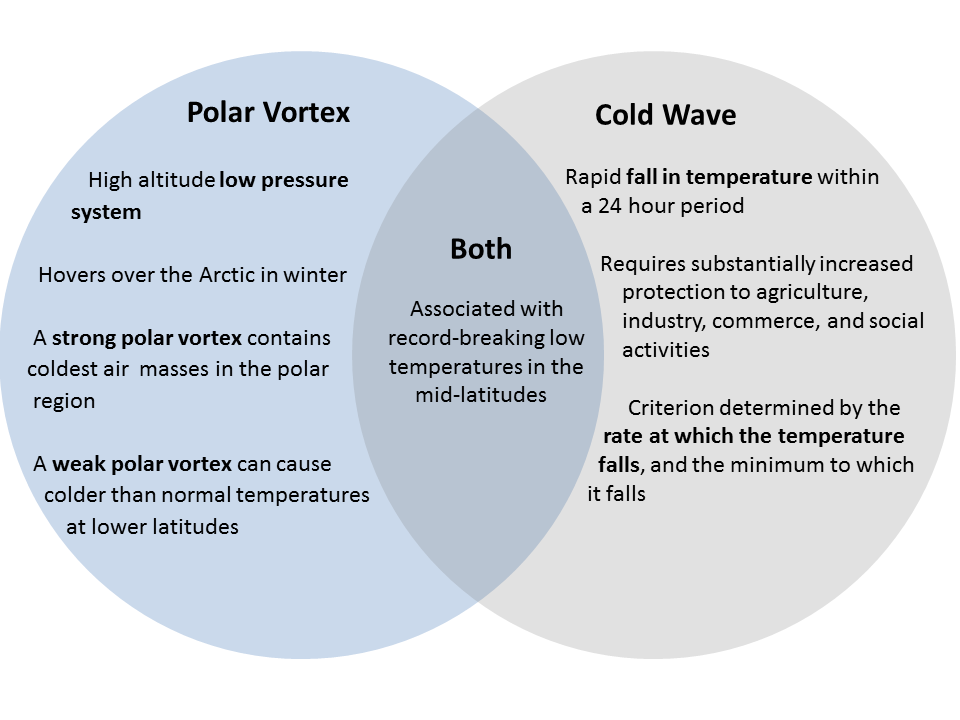

Here are some important differences:

Many cold outbreaks, most really, are just the result of cold fronts, defined as the boundary of an advancing mass of cold air. They are a part of the circulation system of the planet and they restore balance in temperature and moisture in the atmosphere.

Polar vortex in the past, present, and future

Some of the coldest outbreaks in North America have been connected with the polar vortex. In 1985, for example, the polar vortex was located over Quebec and Maine.

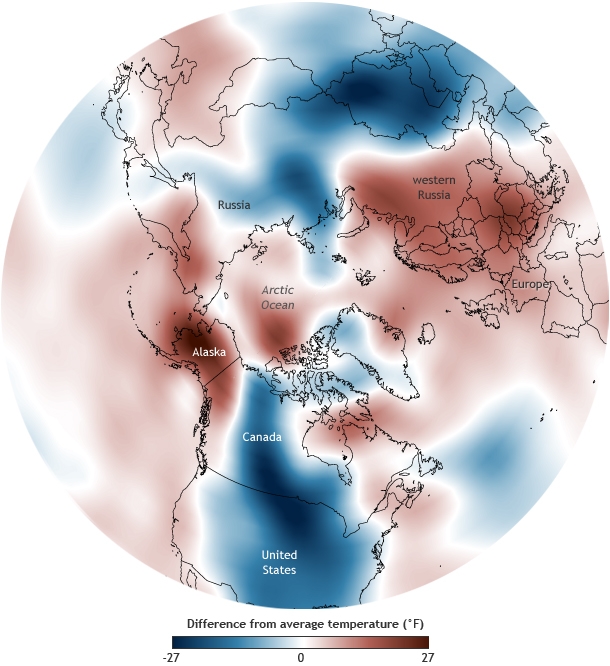

The now-famous polar vortex of January 2014 played a role in making last winter so cold in the eastern US, although it was far from the coldest. However, the opposite happened in the western US and Alaska, which saw record high temperatures.

Air temperatures for January 5-7, 2014, relative to the 1981-2010 average. Image: NOAA Climate.gov, based on NCEP Reanalysis data

An unusual event occurred last week due to the Bering Sea Bomb, associated with typhoon Nuri. The storm essentially created a major undulation in the jet stream pattern with a cascade of effects which eventually affected the polar vortex.

Pronounced meanders in the jet stream and the associated southward migration of the polar vortex may be affected by climate change due to arctic amplification and the loss of sea ice. As the arctic warms, the difference in temperature with the tropics is reduced. The end result is a weaker, wavier, jet stream that allows for southward movements of the polar vortex. Although this is an attractive hypothesis, it should be noted that the historical record is fairly short.

A strong polar vortex (left) and a weak polar vortex (right) with meandering jet stream. Image: NOAA/NASA

Is it the polar vortex outside right now? No. It’s just really cold. It’s an arctic air mass. The polar vortex is currently far north over Hudson Bay.