The drought facing the Western United States is bad. Really bad. It’s become worse faster than the last one. As more of the United States suffers from drought conditions and water supplies are diminishing, water demands are rising. Smaller water supplies combined with increasingly unpredictable weather patterns and other effects of climate change pose an enormous threat by creating a feedback loop that exacerbates drought conditions and increases wildfire risk across the United States.

How bad is it?

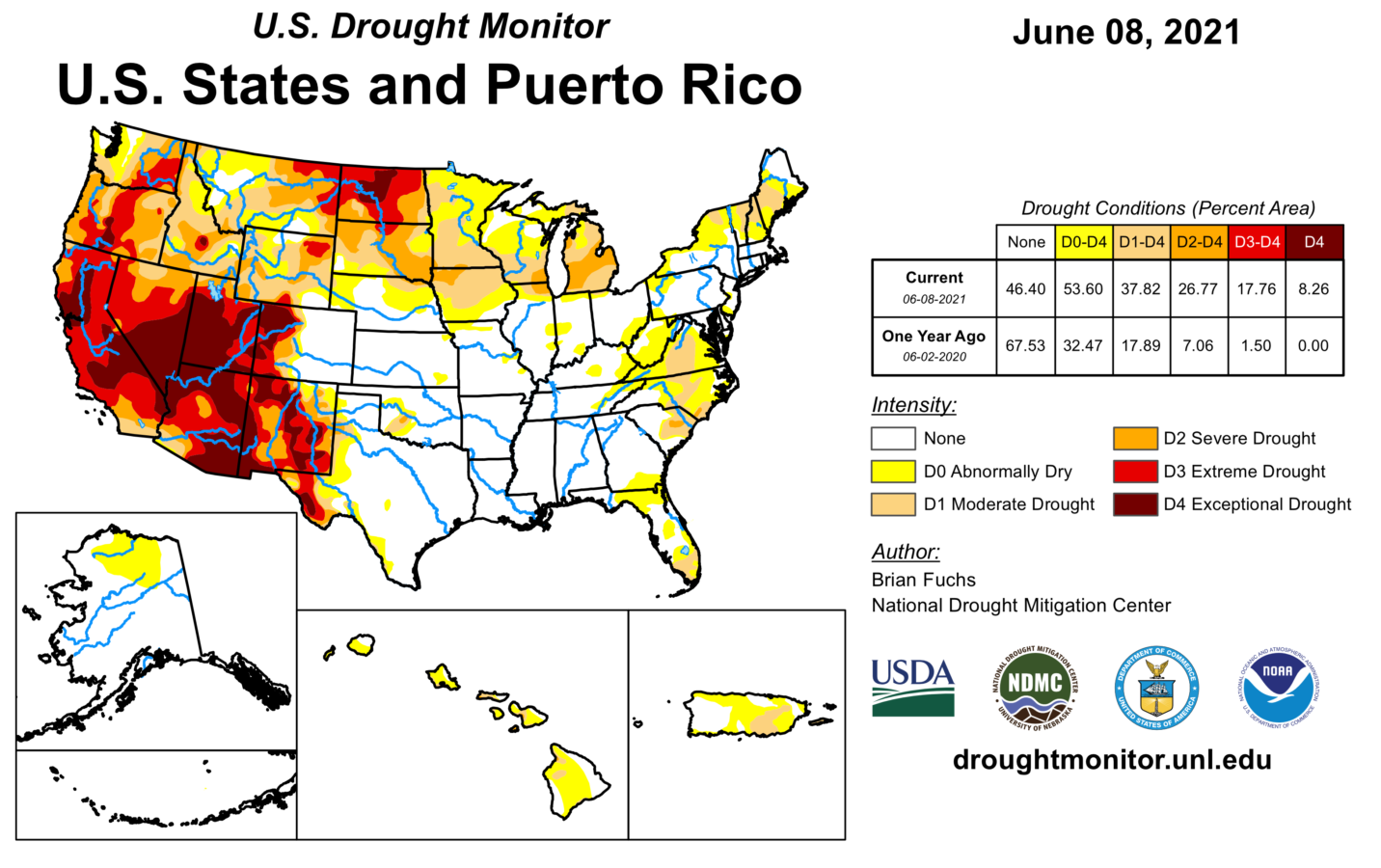

The current drought is a national and international crisis. Considering that California produces more than a third of the vegetables and two-thirds of the fruits and nuts sold in the United States, the drought is affecting more than California and the Southwest. The United States is experiencing what the US Drought Monitor calls “Abnormally Dry Conditions”[1] in more than 50 percent of its area; more than a third is under a “Moderate Drought Conditions.” Almost 10 percent of the country is experiencing an “Exceptional Drought” (Figure 1). These conditions are concentrated primarily in the western states. Nearly the entirety (97 percent) of Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Washington is under Abnormally Dry conditions, and, in many of these states, a quarter or more of their area is experiencing an Exceptional Drought.

How did it get so dry so fast?

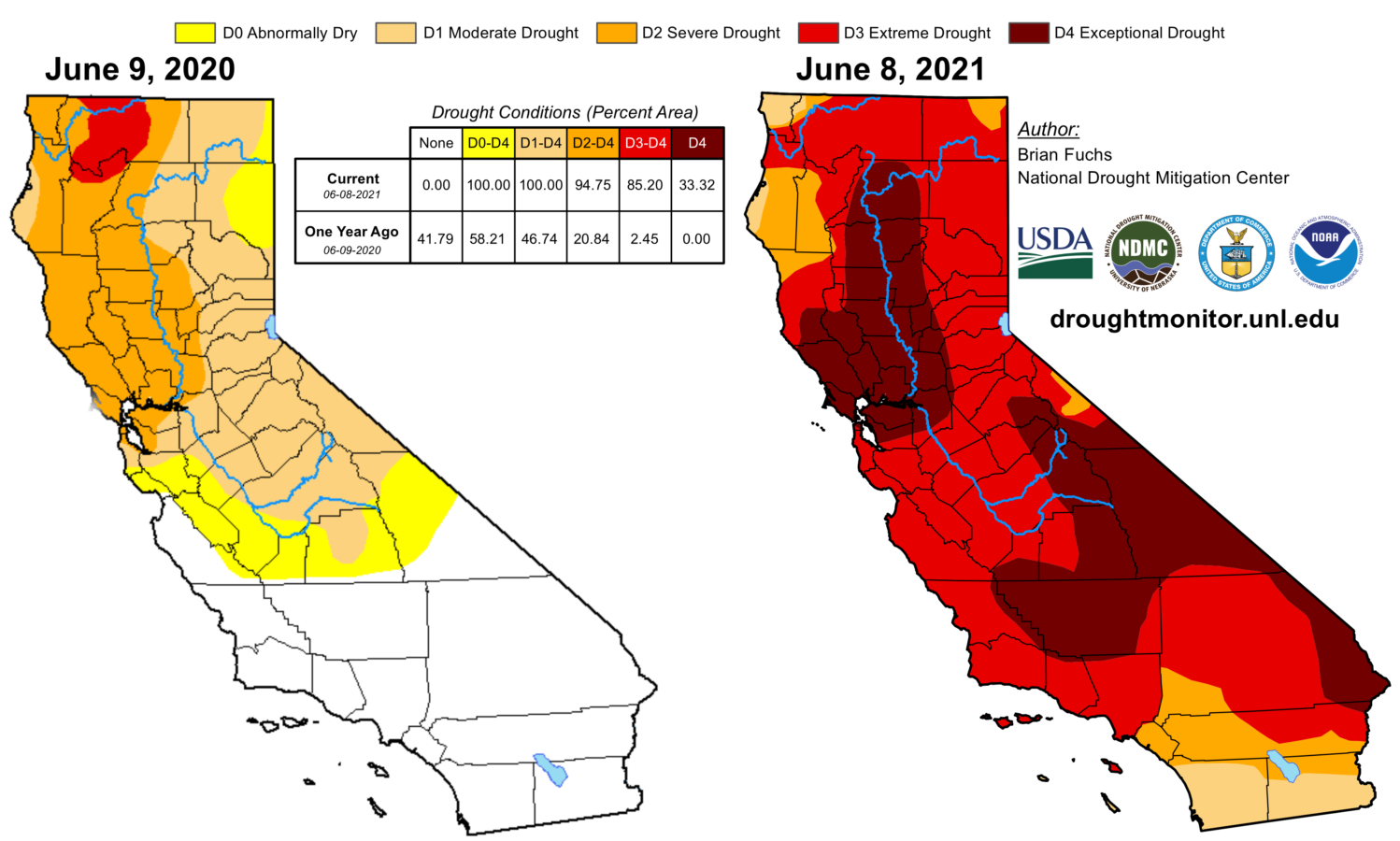

The case of California is worrying. The entire state already passed the Abnormally Dry and Moderate Drought categories. Nearly 95 percent of the state is in a Severe (or worse) Drought; 85 percent of the state is in Extreme Drought; and more than one-third of the state is experiencing Exceptional Drought. Last year was also a dry year, a little bit less dry than this one, but certainly not so dry as to cause the level of drought the state is currently experiencing.

So what’s happening? California has been carrying a deficit on soil moisture. This deficit is not only from last year, but it could be argued that it began with the last drought that ended in 2016. Having two consecutive dry years exacerbates drought conditions and increases the risk of multiple and compounding drought impacts. So the question is, what would a third, or a fourth, or fifth dry year in a row look like?

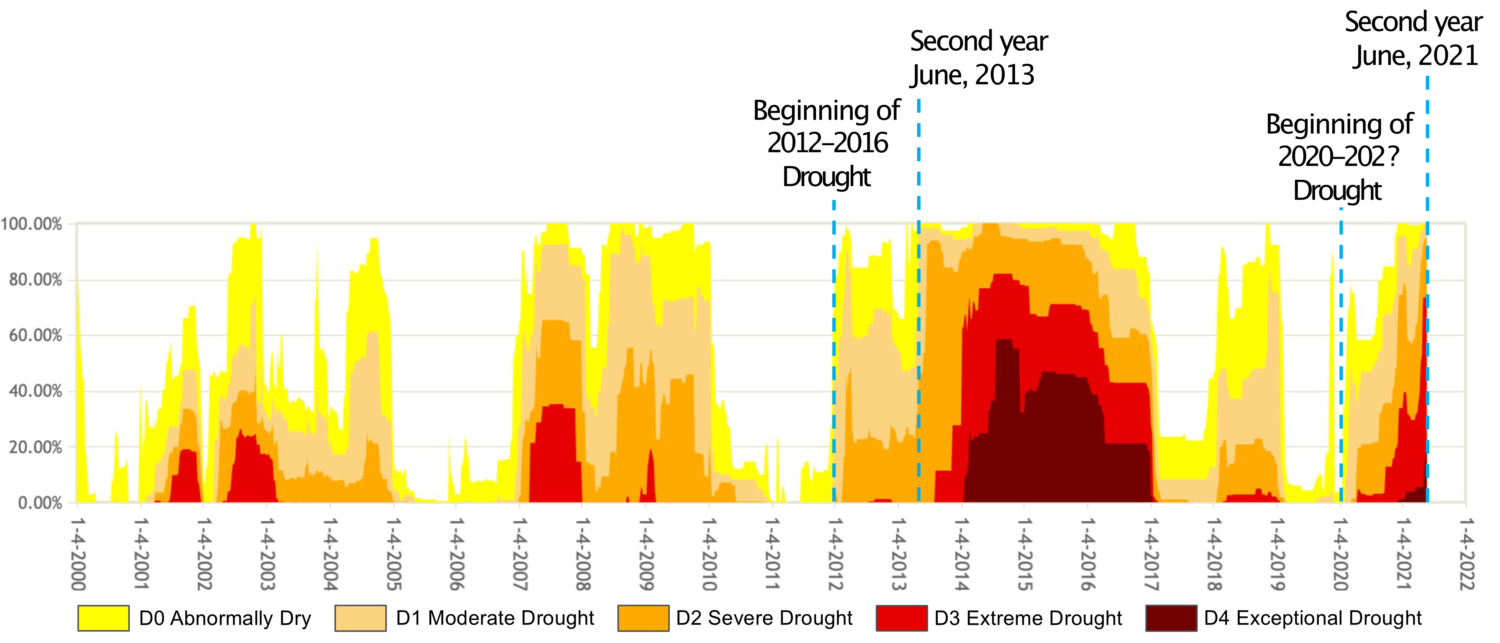

This second year of the California drought is equivalent to the third year of the 2012-2016 drought

There are multiple ways to compare the drought from 2012-2016 with this drought, for example, by considering the amount of water in reservoirs, the snowpack, streamflow in the rivers, or groundwater levels. Here I present a relatively simple comparison. During June of the second year of the 2012 drought, California was not experiencing Extreme Drought or Exceptional Drought conditions (Figure 3). We are in June of the second year of this drought, and 85 percent of the state is under Extreme Drought, and 33 percent of that is under Exceptional Drought. Such conditions didn’t happen until the third year of the 2012-2016 drought. It’s debatable whether we are better prepared for this drought, but we will face harsher conditions if this trend continues.

Despite SGMA, California is more vulnerable and less resilient against droughts

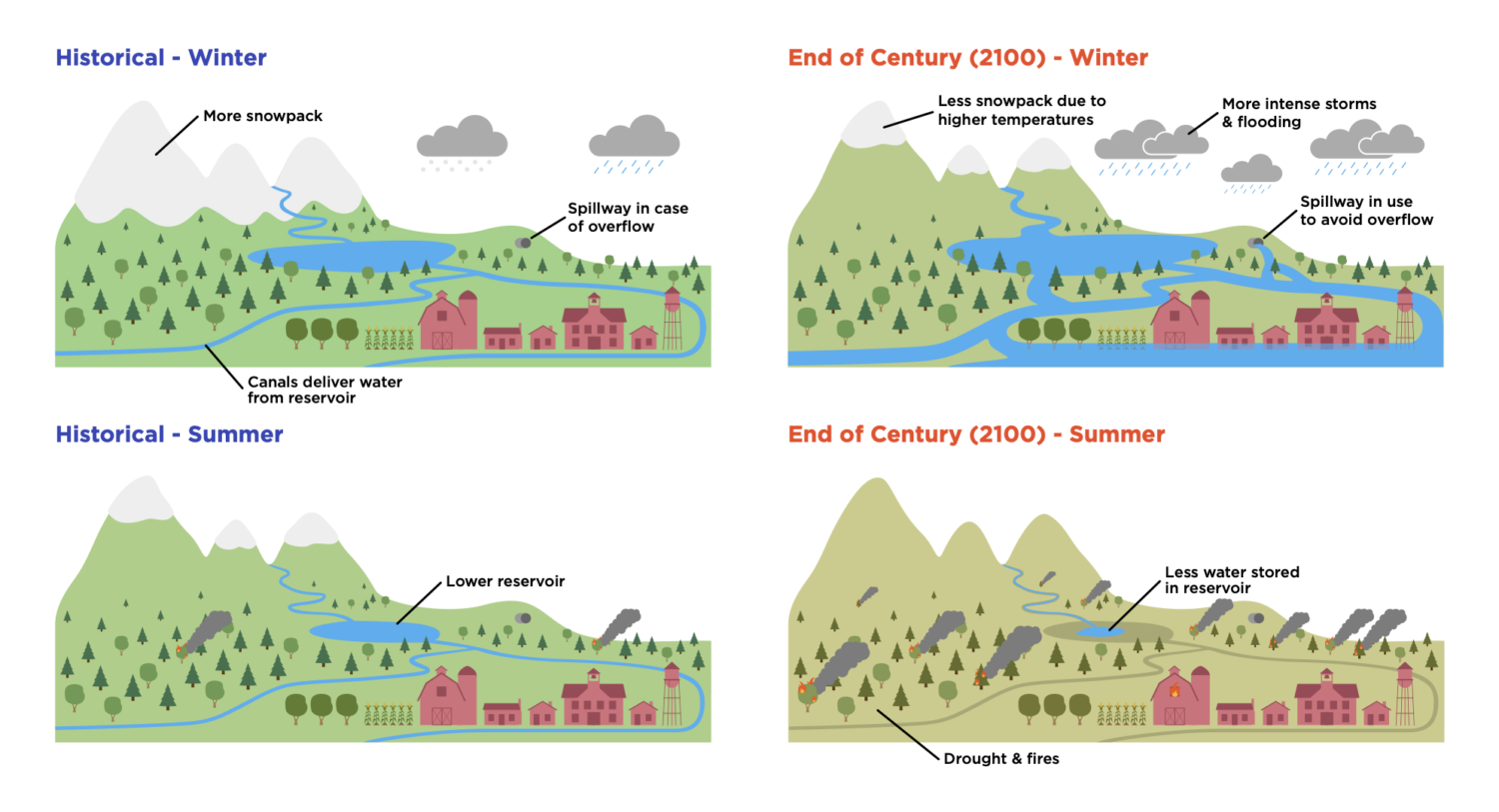

As temperatures warm, more precipitation falls as rain and less as snow, ultimately reducing California’s snowpack. In California, snowpack is vital because it is a natural form of water storage that melts during the spring and fills the reservoirs with water later used for ecosystems, agriculture, and urban needs. Due to rising temperatures, snowpack melted earlier this season. This trend is likely to continue in future years. This means that reservoirs will fill sooner, and water will be released earlier in the winter and spring —before it’s needed. In the summer, farmers are more likely to have to rely even more heavily on groundwater.

As temperatures rise due to climate change, we can expect increases in evaporation and evapotranspiration, reducing water supply and augmenting water demands. Increasing evapotranspiration leads to decreasing soil moisture. This means that even without future changes in precipitation, the drying of soils is likely to cause and exacerbate drought conditions.

The past twenty years show that dry periods are coming at a rate that doesn’t allow us to recover soil moisture or snowpack, so we are becoming more vulnerable and less resilient against droughts.

As there are higher demands and less surface water available, agriculture uses more groundwater. For decades we have been extracting more water from our aquifers than what naturally replenishes them, creating an overdraft. With climate change, groundwater is only going to become scarcer and more critical. While the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) passed in 2014 is intended to manage California’s groundwater resources more effectively, this drought shows that actions are not being implemented fast enough. That makes SGMA implementation incredibly important. Not only should any delays be avoided, but its implementation should be accelerated.

Disadvantaged communities suffer the most during droughts

We can’t talk about the drought without talking about disadvantaged communities in the state. Even without the drought, there are already close to one million people in California without reliable access to drinking water. During the 2012–2016 drought, over 2,600 households across the state that depend on wells for water reported water shortages; almost 80 percent of these were in the San Joaquin Valley. How many wells will go dry this drought?

Droughts not only decrease water availability, they also impact water quality. Decreasing groundwater levels and water quality increase the already heavy dependence on bottled water and interim water tanks in rural communities across the San Joaquin Valley. Water in many communities is contaminated by pesticides, nitrates, arsenic, bacteria, and other contaminants. As we keep overdrafting our groundwater aquifers, some of these contaminants get concentrated, further impacting access to drinking water.

From a climate perspective, this drought is far from over. 2021 is shaping to be the driest year in the last century and one of the driest in the last millennium. The past 20 years have been driving California to the worst water crisis in generations. Part of that is the nature of climate variability in California and part of it is climate change, but a big part is our action or inaction. With climate change exacerbating drought conditions, groundwater is becoming more valuable, and therefore SGMA implementation needs to happen without delay.

[1] The information presented in this blog comes from the U.S. Drought Monitor. The data is produced in collaboration with the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Department of Commerce. They produce these maps using a combination of drought indexes, the best available data, local observations, and experts’ best judgment.