It’s January and it feels like 25 degrees here in Louisville. It’s cold enough that I can see my breath when I walk my dogs. Keep reading and I promise it will make sense why I’m talking to you about extreme heat on this winter day.

Cold temperatures, warm (and concerning) memories

My grandmother, my Nana, died six years ago this month. I credit Nana for showing me how to care for and appreciate the beauty of people and nature. Nana and I had a lot in common including a love for art, pottery, and reading. We also share a sensitivity to the heat. Once, she told me how it was hard to grow up on the farm and not be able to work in the hot sun because it would make her terribly ill.

My grandpa, Nana’s husband, recently told me that he and his dad would wrap glass jugs filled with water in paper to try and keep the water cool on hot days on the farm. Despite their best efforts, it never worked. By the time they carried the water across the field, it was already hot and didn’t help them cool down. It probably kept them from getting dehydrated, though.

My dad’s work requires him to be outdoors in extreme temperatures. Because of my work on extreme heat and climate change, I’m even more aware of the health risks he faces, and I worry about him making it home safely at the end of the day.

He first recognized the danger of heat years ago when he was the only person assigned to a new home construction site and the sun was blazing. There was no shade. He started feeling unwell, so he got in his truck to drive home. The feeling got worse, so he stopped at his friend’s mechanic shop and laid on their cold concrete floor and slowly sipped water until he felt better. I don’t even want to imagine what would have happened if he hadn’t left the site when he did.

Extreme heat affects us all

When I think about global warming, I think about Nana, my grandpa, and my dad—and the millions of people who have no choice but to work outside or in indoor conditions that reach potentially lethal levels of heat. Their jobs are essential, yet they do not have essential protections to keep them healthy and safe at work: water, rest, shade, and training for workers and managers to recognize heat illness symptoms and so they can take action to protect people. And that means, sometimes, that a worker doesn’t make it home at the end of the day.

2021 was one of the hottest years on record. If you think you hear that every year, you’re right. The years just keep getting hotter…which really means that last year is one of the coolest years I’m likely to see for the rest of my life.

This week, my colleagues published a peer-reviewed article which shows the science is clear: rising temperatures will have devastating effects for worker health and livelihoods, and on employers and the wider economy. According to the UCS press release, the report finds:

- In the next few decades, climate change is projected to quadruple US outdoor workers’ exposure to hazardous heat conditions, jeopardizing their health and placing up to $55.4 billion of their earnings at risk annually assuming no reduction in global warming emissions (the path we’re on now).

- The average outdoor worker risks losing more than $1,700 in annual earnings due to extreme heat, though workers in the 10 hardest-hit counties risk losing nearly $7,000 per year on average.

- Over 40 percent of US outdoor workers identify as African American, Black, Hispanic or Latino, despite these groups comprising about 32 percent of the general population. These workers risk losing an estimated $23.5 billion in annual earnings.

My state of Kentucky is certainly not spared from rising risks of extreme heat (and other climate impacts, I wrote about the devastating tornadoes in December and how you can help support local recovery efforts here). Jefferson County, where I live, can expect 79 days per year with a “feels like” temperature that’s above 100°F by late century, but we could reduce that by half if we take bold action on greenhouse gas emissions now).

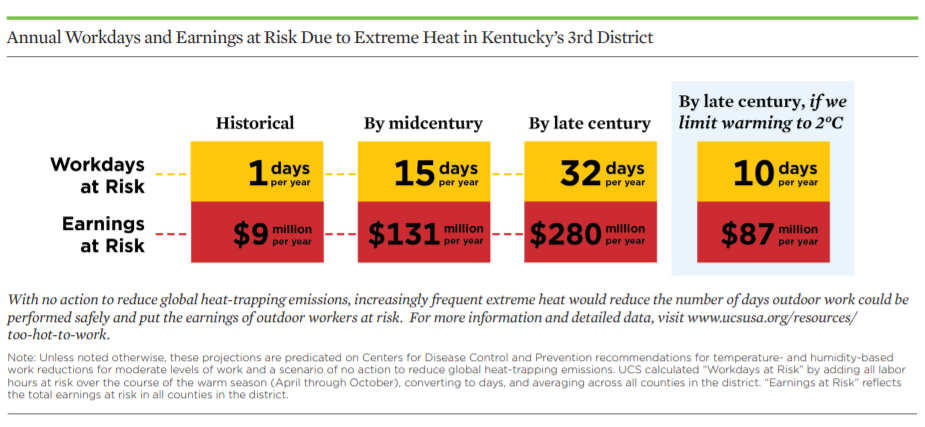

Here’s what that means for workers and their paychecks:

What we need to do now to protect workers

Pass the Build Back Better Act

While we need to do everything in our power to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—this Kentuckian is looking at you, Senator Joe Manchin…listen to my neighbors in West Virginia and pass the Build Back Better Act—we need to protect workers from hazardous heat today.

Support and help inform a heat stress standard by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration

At the end of last year, the Biden administration announced an initiative to protect people from the dangers of extreme heat (read about that here and here). Directing the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to implement a heat stress standard is a critical first step that outdoor workers absolutely need. Years of campaigning by a broad coalition of workers, unions, health experts, and organizations brought us to this celebratory moment.

On average, it take eight years for an OSHA rule to go into effect. Workers’ lives are at stake and we cannot wait that long. Use this tool to comment in support of the rule and demand a quick timeline for the process to give workers urgently- needed protections.

Keep the heat on Congress to act

When you’re feeling angry or climate anxiety is creeping in, call or write a letter to your representative. It is meaningful and a good way to productively channel righteous anger (I’m all for wanting to Hulk-smash things, but that isn’t really going to make the change I want to see in the world). Specifically, tell Congress to pass the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act. Like I said, the OSHA rule could take years to get workers the protections they need. This bill would expedite giving workers essential protections and ensuring life-saving access to water, rest, and shade.

Health experts tell us that, with the right protections in place, every heat illness and death is preventable. Let’s take action now to finally give workers the protections they’ve been fighting for year after year.

Nana, my grandpa, and my dad each told me a story about how heat affects them. They each taught me to be compassionate… and that’s what motivates me to advocate for the health and well-being of all.

Let’s do this.