The Cold War ended 25 years ago this month, according to many historians. On Dec. 2 and 3, 1989, Presidents Bush and Gorbachev met on a ship off the island of Malta in the Mediterranean and announced an end of hostilities between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The two presidents quickly turned to addressing the most dangerous legacy of the Cold War: the bloated nuclear arsenals in both countries. Within a few years, they cut their nuclear stockpiles in half, and have continued to cut them in the decades since. With U.S.-Russian tensions high again, it’s worth remembering what progress has been made.

Reviewing this history is especially important since people may think that the problem of nuclear weapons is too big and too difficult to solve. It’s not.

Arms control successes

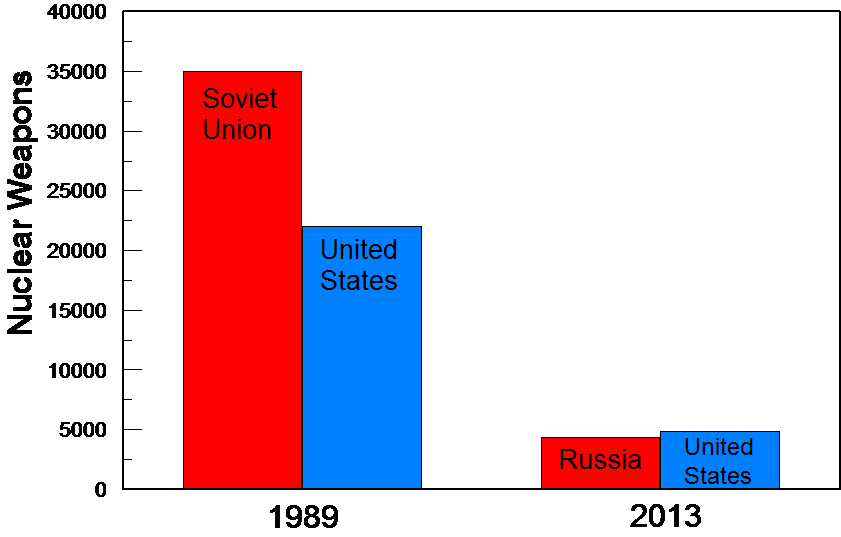

When the Cold War ended, the combined number of warheads in the U.S. and Soviet nuclear arsenals was near its peak, with more than 22,000 nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal and more than 35,000 in Soviet hands.

Today, those numbers have dropped to about 4,800 weapons for the U.S. and 4,300 for Russia, counting both deployed weapons and those kept in storage as a reserve (Fig. 1). Russia currently has about 1,600 weapons deployed on strategic missiles and bombers, and the U.S. has about 2,000.

Fig. 1: Change in the arsenal size following the end of the Cold War. These totals include deployed and stored weapons.

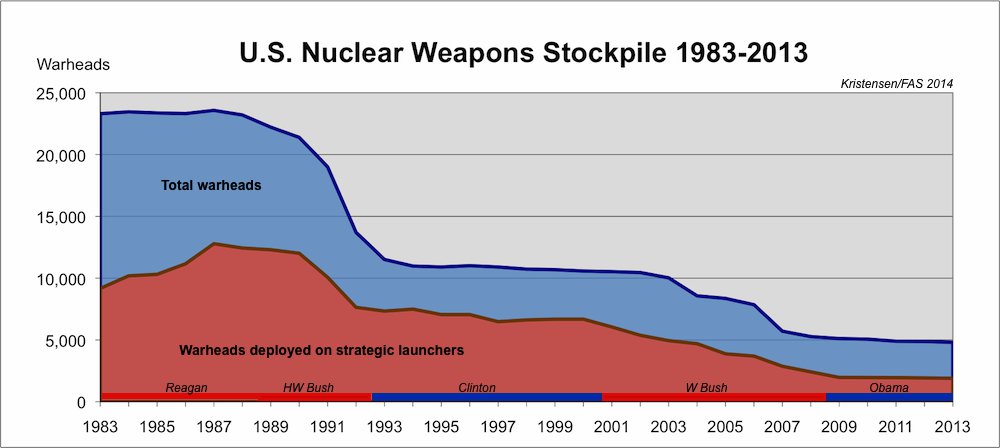

Hans Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists has an interesting graph that shows how the U.S. nuclear arsenal evolved over these years (Fig. 2). The United States made large reductions in the first few years after the Berlin Wall fell. Both Bush and Gorbachev made sweeping cuts to short-range “battlefield” weapons as part of their presidential initiatives. In addition, the START I treaty, signed in 1991, capped the number of deployed long-range weapons at 6,000.

The Clinton administration’s work toward the START II treaty was overtaken by the George W. Bush administration’s SORT treaty, which limited deployed long-range weapons to about 2,200 in each country. President Obama’s New START treaty will, by 2018, reduce that cap to 1,550. (The actual number will be somewhat larger because of how the treaty counts weapons on bombers.)

Fig. 2 (click to enlarge) Source: Hans Kristensen

In addition, in the 1990s the international community negotiated a treaty to end nuclear explosive testing. While the treaty has not yet been ratified by all the countries needed to bring it into force, neither the U.S. nor Russia has conducted a nuclear explosive test since 1992, and no country except North Korea has tested since 1998.

On the other hand …

Despite this progress, of course, the thousands of remaining weapons continue to pose a serious threat to humanity.

The total yield of the deployed U.S. arsenal is equivalent to more than 25,000 Hiroshima bombs, and Russia has a similar number of weapons.

Moreover, the treaties mentioned above do not limit non-deployed weapons in storage. In addition to the 2,000 weapons currently deployed on missiles and bombers, the U.S. keeps some 2,500 warheads in storage as a so-called “hedge” force. The hedge allows the United States to increase its deployed arsenal by putting more weapons on its missiles and bombers, if for any reason it decides to do so. The number of Russian long-range warheads in storage is estimated at about 700.

In addition, the two countries have a total of some 6,000 nuclear warheads that are waiting to be dismantled, but in the meantime are stored intact and could be returned to service. As a result, the U.S. and Russia together still have more than 15,000 intact nuclear weapons between them.

Next steps in the process

Clearly, despite progress to date, there is more to be done. This includes:

- Both countries should further cut the number of deployed long-range weapons. The Pentagon has told President Obama the U.S. needs no more than 1,000-1,100 deployed nuclear warheads, regardless of what Russia does. The president has raised the possibility with Russia of making such cuts jointly. That looks unlikely to happen soon, but Obama should take a page from George H.W. Bush’s playbook and reduce the U.S. arsenal to that level independently of Russia. And chances are good that Russian numbers would fall to a similar level in the coming years.

- Both countries should speed up dismantling those warheads awaiting dismantlement, as a way of making reductions less easily reversible.

- Both countries should slash the number of stored weapons and dismantle a large number of them. A future arms control agreement should put a cap on the total number of deployed and stored weapons.

- Both countries should eliminate the short-range “battlefield” weapons in their arsenals. Currently the United States deploys an estimated 200 such weapons in Europe and stores some 300 in the United States, while Russia is estimated to have 2,000 battlefield weapons in storage.

To reduce the risks posed by nuclear weapons, there are a number of things President Obama could do by presidential order without needing congressional approval. My colleague Stephen Young is writing a set of posts discussing some of these options. A key first step is taking U.S. missile off hair-trigger alert, to reduce the chance of an accidental or erroneous launch.

Good news/bad news

Given all this, the bad news is clear: The United States and Russia still have very large numbers of nuclear weapons, large numbers of them remain on high alert, and the current climate in Washington and Moscow is not conducive to new arms negotiations.

But the good news is that the U.S. and Russia have made much more progress cutting their nuclear arsenals than most people realize, and there are additional, meaningful steps that President Obama can take right now to make further progress and reduce the risk from these weapons.