The Clinton Power Station located 23 miles southeast of Bloomington, Illinois has one General Electric boiling water reactor with a Mark III containment that began operating in 1987.

On December 8, 2013, an electrical fault on a power transformer stopped the flow of electricity to some equipment with the reactor operating near full power. The de-energized equipment caused conditions within the plant to degrade. A few minutes later, the control room operators manually scrammed the reactor per procedures in response to the deteriorating conditions. The NRC dispatched a special inspection team to investigate the cause and its corrective actions.

On December 9, 2017, an electrical fault on a power transformer stopped the flow of electricity to some equipment with the reactor operating near full power. The de-energized equipment caused conditions within the plant to degrade. A few minutes later, the control room operators manually scrammed the reactor per procedures in response to the deteriorating conditions. The NRC dispatched a special inspection team to investigate the cause and its corrective actions. The NRC’s special inspection team issued its report on January 29, 2018.

Same reactor. Same month. Nearly the same day. Same transformer. Same problem. Same outcome. Same NRC response.

Coincidence? Nope. When one does nothing to solve a problem, one invites the problem back. And problems accept the invitations too often.

Setting the Stage(s)

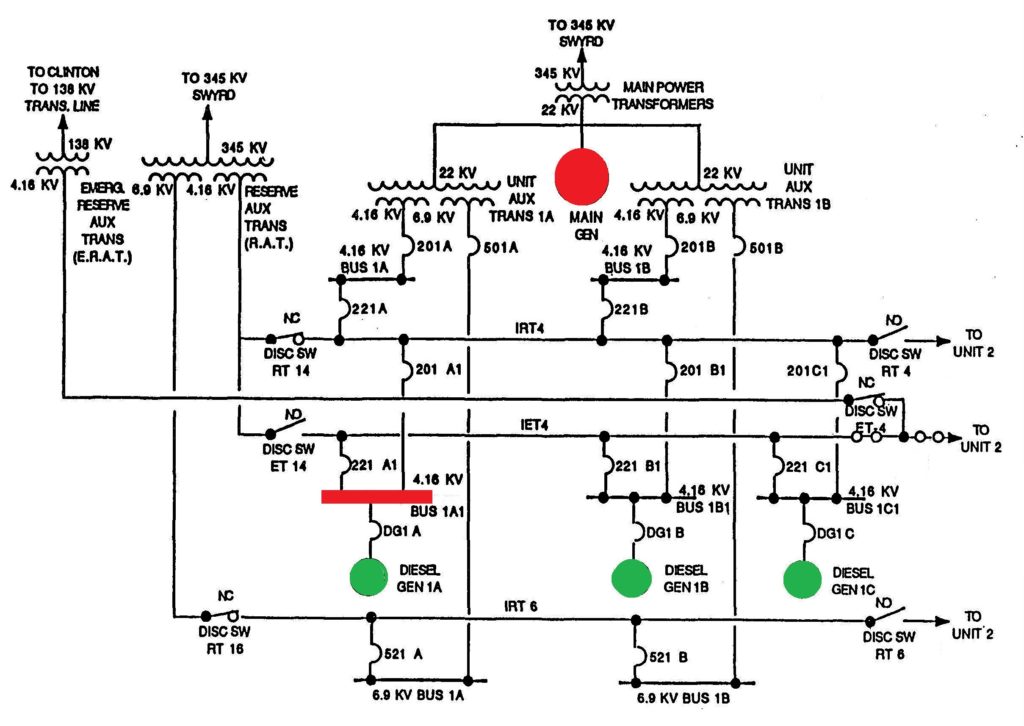

The Clinton reactor was operating near full power on December 8, 2013, and on December 9, 2017. The electricity produced by the main generator (red circle labeled MAIN GEN in Figure 1) at 22 kilovolts (KV) flowed through the main transformers that upped the voltage to 345 KV (345,000 volts) for the transmission lines emanating from the switchyard to carry to residential and industrial customers. Some of the electricity also flowed through the Unit Auxiliary Transformers 1A and 1B that reduced the voltage to 6.9 and 4.16 KV (4,160 volts) for use by plant equipment.

The emergency equipment installed at Clinton to mitigate accidents is subdivided into three divisions. The emergency equipment was in standby mode before things happened. The Division 1 emergency equipment is supplied electrical power from 4,160-volt bus 1A1 (shown in red in Figure 1). This safety bus can be powered from the main generator when the unit is online, from the offsite power grid when the unit is offline, or from emergency diesel generator 1A (shown in green) if none of the other supplies is available. The Divisions 2 and 3 emergency equipment is similarly supplied power from 4,160-volt buses 1B1 and 1C1 respectively, each with three sources of power.

Fig.1 (Source: Clinton Individual Plant Examination Report (1992))

The three buses also provided power to transformers that reduced the voltage down to 480 volts for distribution via the 480-volt buses. For example, 4,160-volt bus 1A1 supplied 480-volt buses A and 1A.

Stage Struck (Twice)

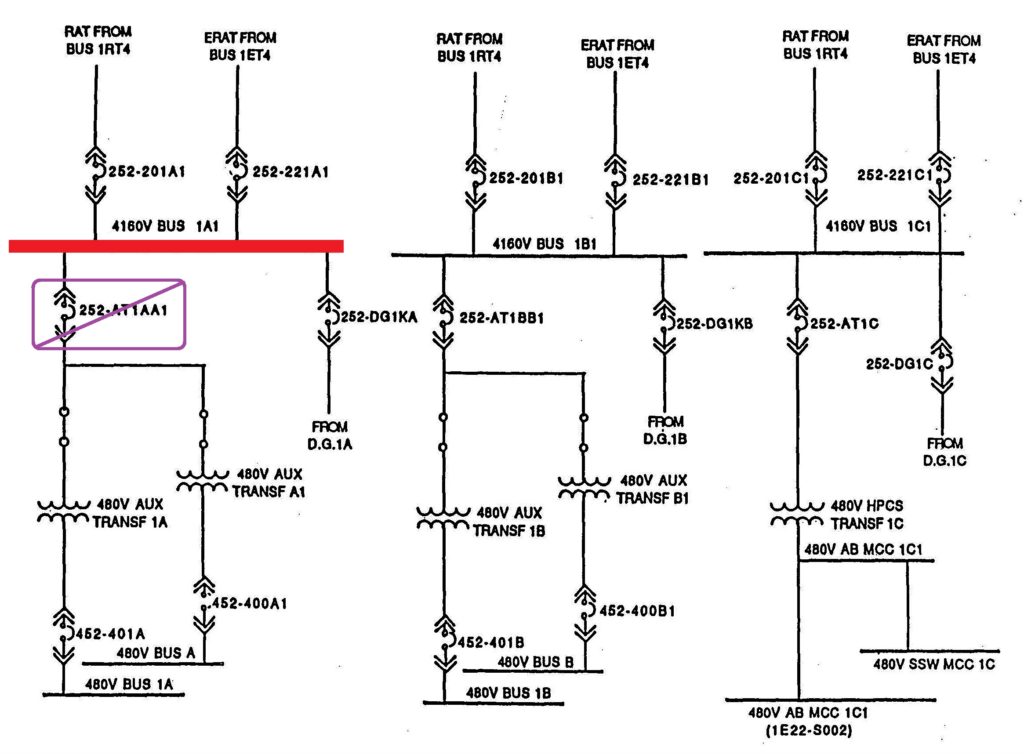

On December 8, 2013, and again on December 9, 2017, an electrical fault on one of the 480-volt auxiliary transformers caused the supply breaker (shown in purple in Figure 2) from 4,160-volt bus 1A1 to open per design. This breaker is normally manually opened and closed by workers to control in-plant power distribution. But this breaker will automatically open to prevent an electrical transient from rippling through the lines to corrupt other equipment.

When the breaker opened, the flow of electricity to 480-volt buses A and 1A stopped, as did the supply of electricity from these 480-volt buses to emergency equipment. It didn’t matter whether electricity from the offsite power grid, the main generator, or emergency diesel generator 1A was supplied to 4,160-volt bus 1A1; no electricity flowed to the 480-volt buses with this electrical breaker open.

Fig. 2 (Source: Clinton Individual Plant Examination Report (1992))

The loss of 480-volt buses A and 1A interrupted the flow of electricity to emergency equipment but did not affect power to non-safety equipment. Consequently, the reactor continued operating near full power.

The emergency equipment powered from 480-volt buses A and 1A included the containment isolation valve on the pipe supplying compressed air to equipment inside the containment building. This valve is designed to fail-safe in the closed position; thus, in response to the loss of power, it closed.

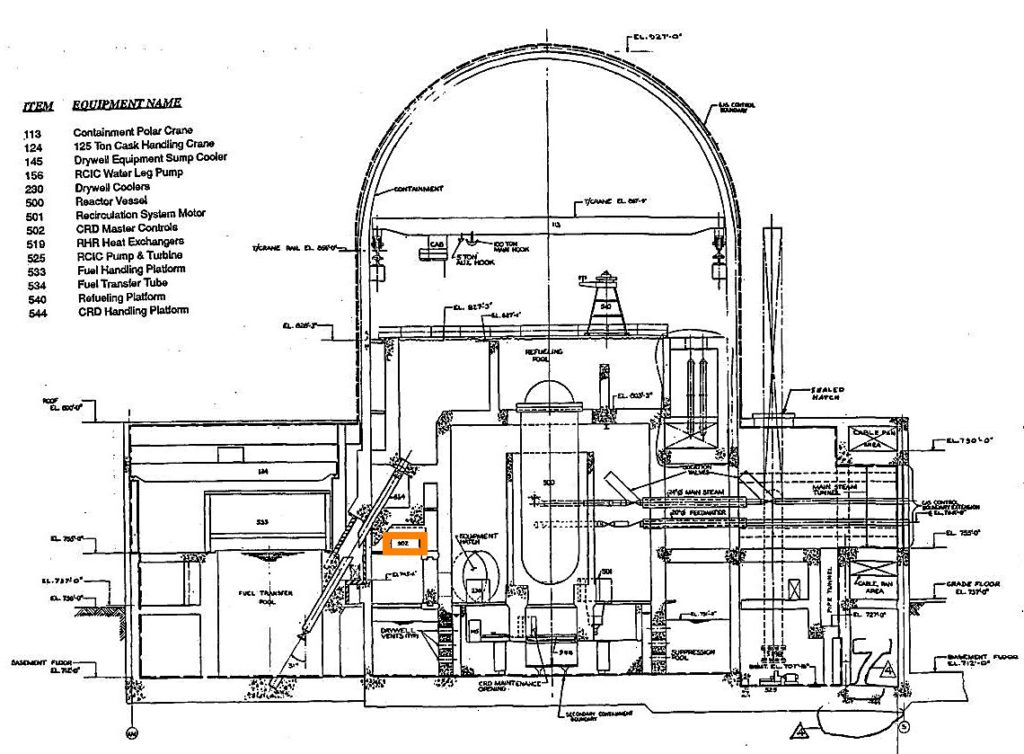

Among the equipment inside containment needing compressed air were the hydraulic control units for the control rod drive (CRD) system (shown in orange in Figure 3). The control rods are positioned using water pistons. Supply water to one side of the piston while venting water from the other side creates a differential pressure causing the control rod to move. Reversing the sides that get water and get vented causes the control rod to move in the opposite direction. Compressed air keeps two scram valves for each control rod closed against coiled springs. Without the compressed air pressure, the springs force the scram valves to open. When the scram valves open, high pressure water is supplied below the pistons while water from above the pistons is vented. As a result, the control rods fully insert into the reactor core within a handful of seconds to stop the nuclear chain reaction.

Fig. 3 (Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission)

Ten minutes after the electrical breaker opened on December 8, 2013, an alarm in the control room sounded to alert the operators about low pressure in the compressed air system. The operators followed procedures and responded to the alarm by manually scramming the reactor.

Four minutes after the electrical breaker opened on December 9, 2017, an alarm in the control room sounded to alert the operators about low pressure in the compressed air system. Two minutes later, other alarms sounded to inform the operators that some of the control rods were moving into the reactor core. They manually scrammed the reactor. (The timing difference between the two events is explained by the amounts of air leaking from piping inside containment and by the operation of pneumatically controlled components inside containment that depleted air from the isolated piping.)

The event had additional complications. The loss of power disabled: (1) the low pressure core spray system, (2) one of the two residual heat removal trains, the reactor core isolation cooling system, and the normal ventilation system for the fuel handling building (the structure on the left side of Figure 3). These losses were to be expected – subdividing the emergency equipment into three divisions and then losing all the power to that division de-energizes about one-third of the emergency equipment.

Fortunately, the loss of some emergency equipment in this case was tolerable because there was no emergency for the equipment to mitigate. The operators used non-safety equipment powered from the offsite grid and some of the emergency equipment from Divisions 2 and 3 to safely shut down the reactor. The operators anticipated that the loss of compressed air to equipment inside containment would eventually cause the main steam isolation valves to close, taking away the normal means of removing decay heat from the reactor core. The operators opened other valves before the main steam isolation valves close to provide an alternate means of sustaining this heat removal path. About 30 hours after the event began, the operators placed the reactor into a cold shut down mode, within the time frame established by the plant’s safety studies.

Staging a Repeat Performance

Workers replaced the failed Division 1 transformer following the December 2013 event. Clinton has five safety-related and 24 non-safety-related 4,160-volt to 480-volt transformers, including the one that failed in 2013. Following the 2013 failure, a plan was developed to install windows in the transformer cabinets to allow the temperature of the windings inside to be monitored using infrared detectors. Rising temperatures would indicate winding degradation which could lead to failure of the transformer.

But the planned installation of the infrared detection systems was canceled because the transformers were already equipped with thermocouples that could be used to detect degradation. Then the owner stopped monitoring the transformer thermocouples in 2015.

Plan B (or C?) involved developing a procedure for Doble testing of these 29 transformers that would trend performance and detect degradation. The Doble testing was identified in October 2016 as a Corrective Action to Prevent Recurrence (CAPR) from the 2013 transformer failure event. The Doble testing procedure was issued on November 18, 2016.

Clinton was shut down on May 8, 2017, for a refueling outage. The activities scheduled during the refueling outage included performing the Doble testing on the Division 2 4,160-volt to 480-volt transformers. But that work was canceled because it was estimated to extend the length of the refueling outage by three whole days. So, Clinton restarted on May 29, 2017, without the Doble testing being conducted. As noted by the NRC special inspection team dispatched to Clinton following the repeat event in 2017: “…the inspectors determined that revising the model work orders [i.e., the Doble test procedure] alone was not a CAPR. In order for the CAPR to be considered implemented, the licensee needed to complete actual Doble testing of the transformers.”

The NRC’s special inspection team also identified a glitch with how some of the non-safety-related transformers were handled within the preventative maintenance program. A company procedure required components whose failure would result in a reactor scram to be included in the preventative maintenance program to lessen the likelihood of failures (and more importantly, costly scrams). In response to NRC’s questions, workers stated that three of the non-safety-related transformers could fail and cause a reactor scram, but that these transformers were not covered by the preventative maintenance program.

Plan C (or D?) now calls for replacing all five safety-related transformers: the two Division 2 transformers in 2018 and the single Division 3 transformer in 2021. The two Division 1 transformers have already been replaced following their failures. A decision whether to replace the 24 non-safety-related transformers awaits a determination about seeking a 20-year extension to the reactor’s operating license.

NRC Sanctions

The NRC’s special inspection team identified two findings both characterized as Green in the agency’s green, white, yellow and red classification system.

One finding was the violation of 10 CFR Part 50, Appendix B, Criterion XVI, “Corrective Actions,” for failing to implement measures to preclude repetition of a significant condition adverse to quality. Specifically, the fixes identified by the owner following the December 2013 transformer failure were not implemented, enabling the December 2017 transformer to fail.

The other finding was the failure to follow procedures for placing equipment within the preventative maintenance program. Per procedure, three of the non-safety-related transformers should have been covered by the preventative maintenance program but were not.

UCS Perspective

Glass half-full: Clinton started operating in 1987 and didn’t experience a 4,160-volt to 480-volt transformer failure until late 2013. Apparently, transformer failures are exceedingly rare events such that lightning won’t strike twice.

Glass half-empty: All the aging transformers at Clinton were over 25 years old and heading towards, if not already in, the wear out region of the bathtub curve. Lightning may not strike twice, but an aging jackhammer strikes lots of times (until it breaks).

Could another untested, unreplaced aging transformer fail at Clinton? You bet your glass.

Fig. 4 (Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission)