The New York Times found an odd way to commemorate this year’s anniversaries of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombings—by publishing on August 9 an opinion piece by columnist Bret Stephens titled “The U.S. Needs More Nukes.” Matt Korda has a nice article about it in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. I wanted to add a few comments of my own.

Stephens begins his essay by claiming that America’s allies are skeptical of the United States as a military partner because of President Trump. That is probably true, but linking their skepticism to the idea that the US nuclear arsenal is somehow deficient is patently absurd. What prompts their skepticism is the Trump administration’s dangerously provocative actions, its unpredictability, as well as President Trump’s penchant for devaluing traditional alliances.

Stephens’s overall argument seems to be that we would be better off without arms control agreements because it is possible that states might cheat on them. But arguing that arms control has failed and should be discarded because it hasn’t worked perfectly is like saying we should get rid of laws against murder since they haven’t stopped all murders.

Treaties create transparency, predictability, and constraints that both sides agree are beneficial, and they set up verification measure to ensure that any meaningful cheating is detected. US negotiators have gone to great lengths to design verification protocols to minimize the chances for and consequences of cheating, and have routinely stated that the United States is better off with the stability and constraints that such agreements provide than with an unrestrained arms race.

No, there’s no “gap” in nuclear capabilities

Let’s take a closer look at some of the other major problems with Stephens’ argument.

- There is no “gap” in US nuclear capabilities, as Stephens claims. The United States already has a wide range of low-yield nuclear weapons in its arsenal (Fig. 1). It also has more than sufficient nuclear weapons to ensure its ability to provide deterrence for itself and its allies. Withdrawing from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty to allow it to deploy even more nuclear weapons would not improve US security. Rather, it would allow Russia to continue to build up its own arsenal unconstrained, leading both countries toward a new arms race.

- Stephens’ insinuation that NATO countries would like the United States to withdraw from the INF Treaty and build more nuclear weapons does not match reality. The Pershing missiles the Reagan administration began deploying in the early 1980s proved to be extremely unpopular with Europeans, who staged massive demonstrations demanding their removal at the height of the Cold War. That backlash was a key reason why the United States ultimately negotiated the INF Treaty in 1987. European sentiment has not changed much since then. There is opposition to NATO states serving as a base for conventional US intermediate-range missiles such as the ground-launched conventional cruise missile Congress greenlighted in the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act.

- It’s true that Taiwan is potentially the most dangerous flashpoint between the United States and China. But when Chinese military planners analyze how likely the United States is to intervene if the Chinese military moved against the island, their conclusion is unlikely to be influenced by the specific number or types of weapons the United States possesses.

- Stephens cites a Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) projection that China could double its nuclear arsenal within a decade, but it’s important to recognize that DIA estimates of China’s nuclear capabilities are often far higher than those of other US intelligence agencies and have not proved to be accurate. China’s nuclear arsenal today is smaller than the US nuclear arsenal was in 1950. It has been slowly modernizing its nuclear force over the years but it is far less capable than the US nuclear force, and will remain that way even if the United States did nothing. But the United States is hardly standing still: it has a trillion-dollar plan to upgrade and/or replace all three legs of the nuclear triad—submarines, land-based missiles, and bombers—and their associated warheads over the next 30 years.

Many of the Stephens’ examples of cheating are either not cheating or are cases in which the existence of a treaty allowed the issue to be resolved. For example:

- “Iran’s resumption of nuclear work” is a result of the Trump administration pulling out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal), which was successfully constraining this work—exactly what an arms control agreement is designed to do.

- The Soviet Union did build a radar at Krasznoyarsk in violation of the Antiballistic Missile Treaty, but Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush both confronted Moscow using mechanisms provided by the treaty, and the Russians ultimately dismantled it. (The treaty itself remained in force until the President George W. Bush withdrew from it in 2002 in order to build missile defenses.)

Cold War logic

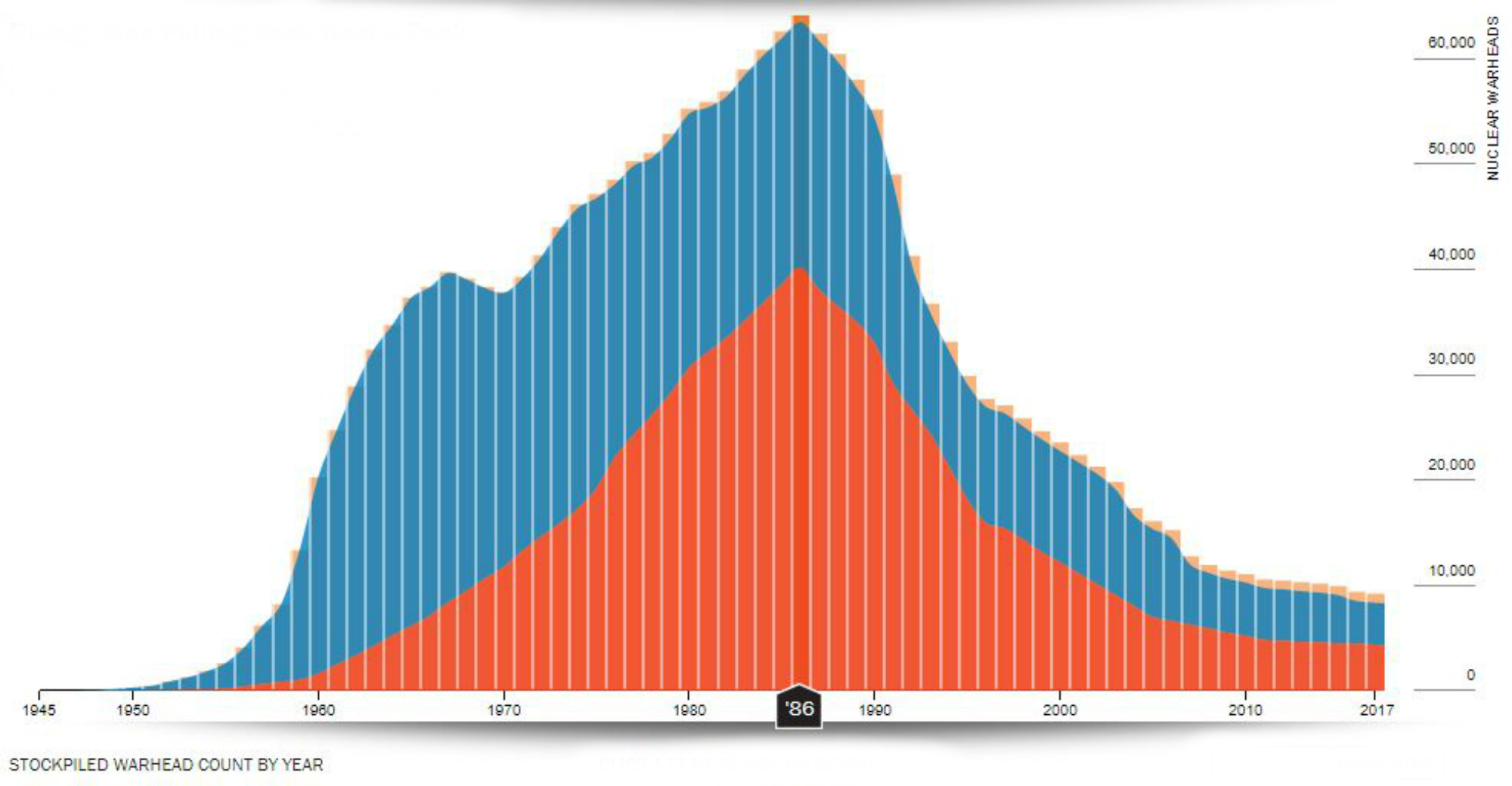

It was Cold War logic like Bret Stephens’ that led the United States and Soviet Union to build up arsenals of more than 60,000 nuclear weapons (Fig. 2). Various crises, misunderstandings and near-misses have demonstrated the lethal insanity of such thinking. Having lived with this intractable face-off firsthand, leaders on both sides sought ways to bring the situation under some semblance of control before they stumbled into an unwanted nuclear war. Their answer—endorsed not only by diplomats, but by military leaders as well—was to pursue a series of arms control treaties to limit the numbers and types of weapons they each possessed. And both sides agreed that those treaties enhanced their own national security. Those agreements eventually helped to bring the US and Russian nuclear arsenals down to about 4,000 each, with fewer than 2,000 deployed by each country. That’s still a lot, but a substantial improvement compared to the unconstrained days of the early arms race.

Fig. 2. US (blue) and Soviet/Russian (red) and rest-of-world (tan) nuclear arsenals over time. The INF Treaty was signed in 1987. (Source: Nuclear Notebook)

It took decades of hard work and negotiations to reach the point we are at today. Those like Bret Stephens who seem to forget why negotiators did all that work could undo it in much less time, and that is the direction that we currently seem to be heading under the Trump administration. The world was lucky to survive the Cold War with little more than a rapidly fading memory of the fear that living in such a world provoked, but humanity may not be so lucky the next time.