The Justice40 proclamation by President Biden is an exciting and long-overdue commitment by the federal government to achieving environmental justice for communities overburdened with climatic and environmental burdens. In order to guide the prioritization of communities to receive Justice40 investments, the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) recently released its first version of an online web mapping tool called the Climate & Environmental Justice Screening Tool (CEJST). This tool integrates many indicators of socio-economic and environmental disadvantage at the census tract level for all 50 states and the District of Columbia, but a much more limited set of indicators for Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands.

Inadequate and incomplete characterizations

CEJST includes indicators of disadvantage for the 50 states and the District of Columbia related to climate change, energy efficiency, sustainable housing, ambient air and water pollution, and workforce development, to name a few. However, only those under the workforce development category have been implemented for Puerto Rico, and these are insufficient to assess population disadvantage in the island territory. For example, one indicator used for Puerto Rico is linguistic isolation, that is, the fraction of the population that cannot communicate in, or understand the English language. While in the US that is a significant barrier to obtaining information about—and procuring—many services, daily life in Puerto Rico takes place in Spanish, and the Puerto Rican government offers its services in Spanish, so this variable is inadequate and not helpful to assess relative disadvantage in Puerto Rico.

Each of the indicators for census tracts has been ranked as a percentile value among all census tracts in the US and the territories. For Puerto Rico, this introduces a distorted picture of socio-economic disadvantage. As a result, 87% of communities in Puerto Rico have been classified as disadvantaged by CEJST. This is because rates of poverty and unemployment in Puerto Rico (two key categories in the “workforce development” category developed for the island) are much higher than in most places in the US. While it is important and factual to recognize that Puerto Ricans in the territory face significant social and economic disadvantages in comparison to people in the US, this classification does not convey the large social and economic disparities that exist within Puerto Rico.

Federal agencies have the necessary data

What’s missing in terms of data? A number of categories implemented in CEJST for the 50 states and the District of Columbia have not been implemented for Puerto Rico. To be fair, some indicators used for states and the District of Columbia are not available for Puerto Rico because federal agencies have not created them, and CEQ’s mandate for the screening tool is to integrate the datasets, not to create or improve the data. In some cases where the same data are not available, there are alternatives that should be explored by CEQ in the next revision of the tool. But many data are in fact available. For example:

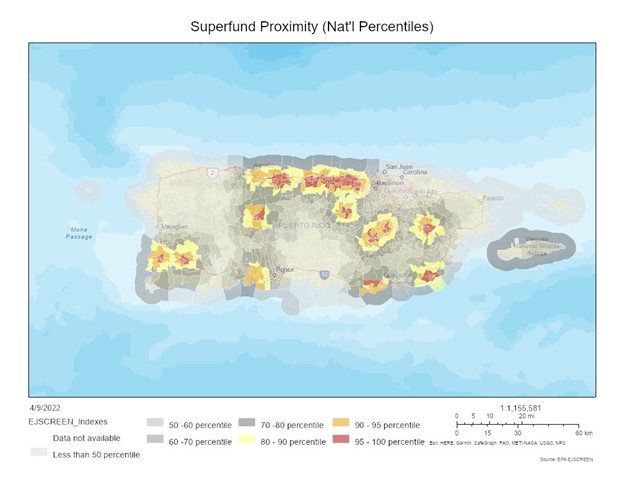

Legacy pollution: Puerto Rico is host to many sources of toxic and other industrial pollution—grouped in CEJST under the “reduction and remediation of legacy pollution” category. The data used to assess proximity to these sources in the 50 states and the District of Columbia are listings of Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities (TSDF), Risk Management Plan (RMP), and National Priorities List (Superfund) sites and facilities, and the EPA has integrated these in EJSCREEN, the environmental justice screening tool. These data are also available for Puerto Rico and should be integrated into CEJST’s assessment for communities in Puerto Rico under the “reduction and remediation of legacy pollution” category.

Climate change: While the source for this category for the 50 states and the District of Columbia—FEMA’s National Risk Index (NRI)—does not include data for Puerto Rico, NOAA has developed a Coastal Flood Hazards dataset that includes Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands, and has been implemented in EJSCREEN. While these data may not allow a valuation of population, agricultural crops, and building loss from extreme weather similar to that provided by the NRI, the coastal flood hazards data provides a cumulative assessment of multiple types of coastal hazards that communities are exposed to. Many of these are related to climate change, for example, flood zones, sea-level rise, and storm surge based on hurricane categories.

Critical clean water and waste infrastructure: The characterization of critical clean water and waste infrastructure indicators in Puerto Rico is absent in CEJST. While the source for this category for the 50 states and the District of Columbia—EPA’s Risk-Screening Enviromental Indicators (RSEI)—does not include water discharge modeling results for Puerto Rico, it does include point sources of air and water discharges in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. These data should be integrated into CEJST’s assessment for communities in Puerto Rico under the “critical clean water and waste infrastructure” category that is present in CEJST for the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Energy burden: The assessment of energy burdens is also absent in CEJST for Puerto Rico. The source for assessing energy burdens for the 50 states and the District of Columbia—the Department of Energy’s Low-Income Energy Affordability Data (LEAD) tool includes results for Puerto Rico, so these data could be easily incorporated.

Clean transit: These indicators are also absent in CEJST for Puerto Rico. The data sources for this category for the 50 states and the District of Columbia are traffic proximity and volume from the Department of Transportation (traffic proximity and volume), and EPA’s National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA, diesel particulate matter exposure). Both data sources have been implemented in EPA EJSCREEN and include results for Puerto Rico. These data should be integrated into CEJST’s assessment for communities in Puerto Rico under the “clean transit” category present in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Housing cost burden: The characterization of housing cost burden indicators in Puerto Rico is absent in CEJST. The data sources for this category for the 50 states and the District of Columbia—the Department of Housing’s Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy dataset—includes results for Puerto Rico. These data should be integrated into CEJST’s assessment for communities in Puerto Rico under the “housing cost burden” category present in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Clearly, many datasets available for the rest of the US are also available for Puerto Rico, and future iterations of CEJST should integrate as many as possible to provide an accurate assessment of social, economic, and climatic disadvantage there.

A different approach to assessing population disadvantage

Besides gaps in data, the ways in which CEJST is framing population disadvantage in Puerto Rico does not provide an accurate picture of the situation in the territory. The composition of the population, its climate and energy challenges, and the island’s fiscal and governance structure shape the current and future population disadvantage.

The population structure in Puerto Rico is very rapidly diverging from that of the US. Population in Puerto Rico declined nearly by 12% over the last decade. People in their most productive years are leaving the island (mostly relocating to the United States) as evidenced by the thinning bands in the 20-39 years of categories in the population pyramid below.

Energy burdens are particularly pernicious in Puerto Rico. Since LUMA Energy took over the distribution of electricity following a contract award process full of irregularities, Puerto Rico has experienced three major blackouts. The most recent one occurred a few days ago, leaving over one million Puerto Ricans without power for at least one full day, which came a few days after the sixth increase in the price of the kilowatt-hour in Puerto Rico since LUMA started operations. And electricity prices in Puerto Rico are already much higher than the average in the United States.

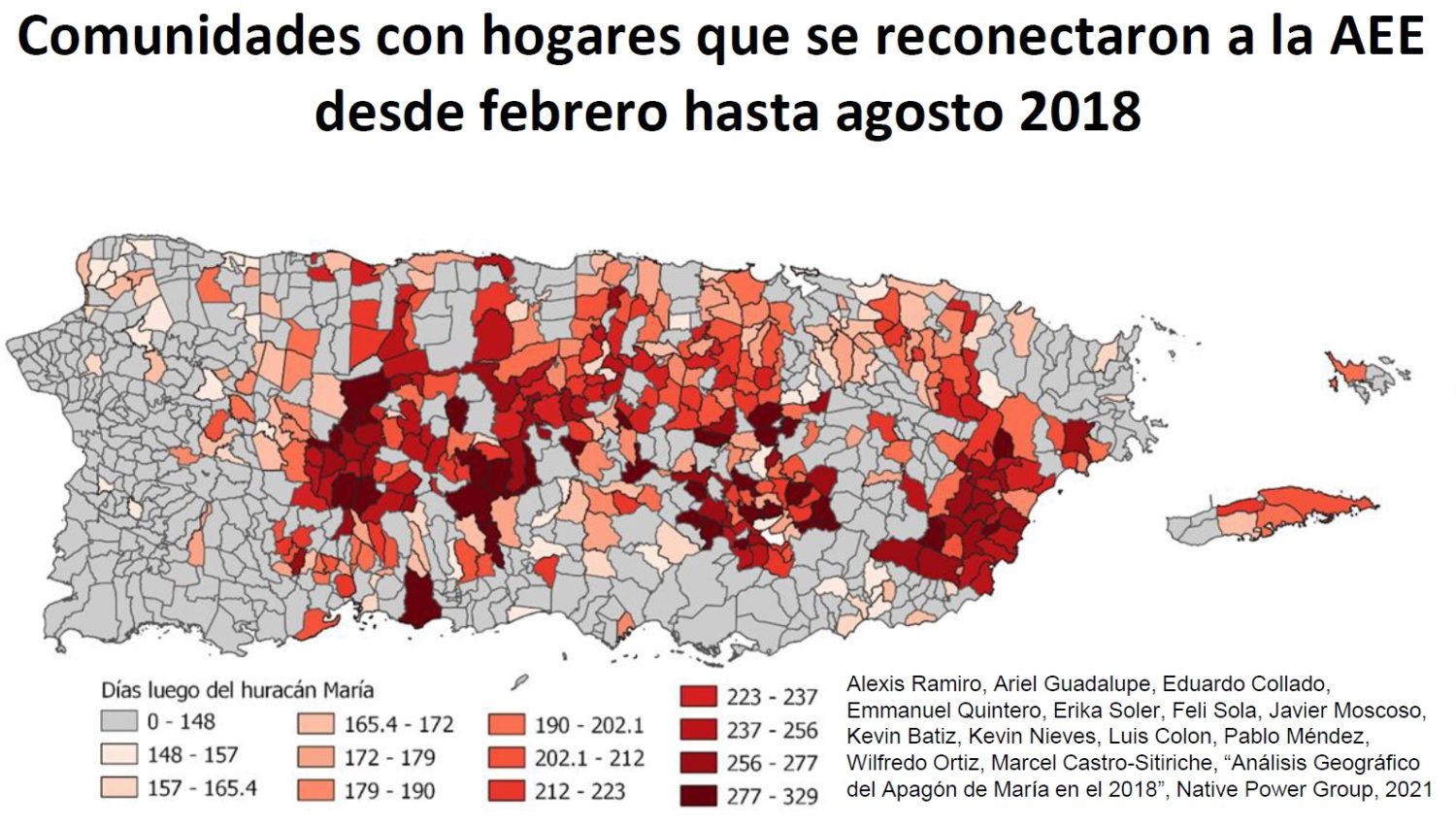

Following Hurricane María, many communities went without electricity for long periods of time. Some had to wait between 5 and 10 months following the storm for power restoration, as shown in the map below. And these communities are largely also rural areas with the highest levels of poverty and unemployment, and low formal educational attainment. These communities are likely to be the ones at highest risk when the next hurricane hits Puerto Rico.

Finally, the Financial Oversight & Management Board (FOMB) created by the congressional law PROMESA (Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act) has imposed devastating austerity measures and debt restructuring plans that are hurting Puerto Ricans and impeding an economic growth and recovery. Last year, a joint report by the Center for Popular Democracy and the Action Center on Race and the Economy described the pernicious effects of the FOMB’s actions for Puerto Ricans:

During its tenure, the [Financial Oversight & Management] Board has privatized the publicly-owned power grid and pushed rate hikes on utility customers; weakened labor protections for workers; imposed massive cuts in education funding and over 250 school closures; proposed cutting pensions for public sector workers by 8.5%; imposed significant cuts to healthcare and the state-run Medicaid program; and narrowed eligibility for vital food assistance programs. These austerity measures are being imposed on communities that already face an enormous degree of economic precarity. Over 43% of the island lives in poverty, one-third of the island’s residents are food insecure, and the unemployment rate is consistently nearly double that in the United States.

The Center for Popular Democracy and Action Center on Race & the Economy. PROMESA has failed: How a Colonial Board is enriching Wall Street and hurting Puerto Ricans. September 2021. https://www.populardemocracy.org/sites/default/files/%5BENGLISH%5D%20PROMESA%20Has%20Failed%20Report%20CPD%20ACRE%209-14-2021%20FINAL.pdf

As I have argued, social, economic, and climatic vulnerability in Puerto Rico has been built over decades in Puerto Rico. Nearly five years after Hurricane María, Puerto Rico’s recovery remains incomplete and Puerto Ricans living on the island and in the diaspora wonder how the territory’s fragile infrastructure will be able to withstand the inevitable seasonal extreme weather from hurricanes and flooding augmented by climate change. Implementing Justice40 in disadvantaged communities in Puerto Rico can help strengthen infrastructure and increase the resilience of Puerto Ricans, but it requires an approach that considers the specific population and infrastructure vulnerabilities as well as climate and energy challenges that shape population disadvantage in the territory.