For weeks now, news alerts from Arkansas have piled up in my inbox, documenting the tragic trend of fast-rising COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations in that state. Yesterday, the governor made a grim announcement: ICU beds in the state are full. I don’t live in Arkansas, but thousands of poultry workers and farmers do, and most of them produce chicken for Tyson Foods, among the state’s largest employers. Knowing what I know about the sordid COVID history of the nation’s largest meat and poultry company—Tyson was responsible for one-third of all occupational cases in Arkansas between May 2020 and April 2021—and how the company treats its workers generally, I’ve wondered about possible connections.

To what degree is Tyson responsible for the rampant spread of the virus this summer in communities where it operates? What could the company—which bills itself as a good neighbor and likes to call its workers “family”—have done to prevent it? And will Tyson’s recently announced vaccination mandate for employees help stem the tide? Clear answers to those questions may be unknowable, but the data contain some hints.

Tyson’s HQ is in a COVID bullseye

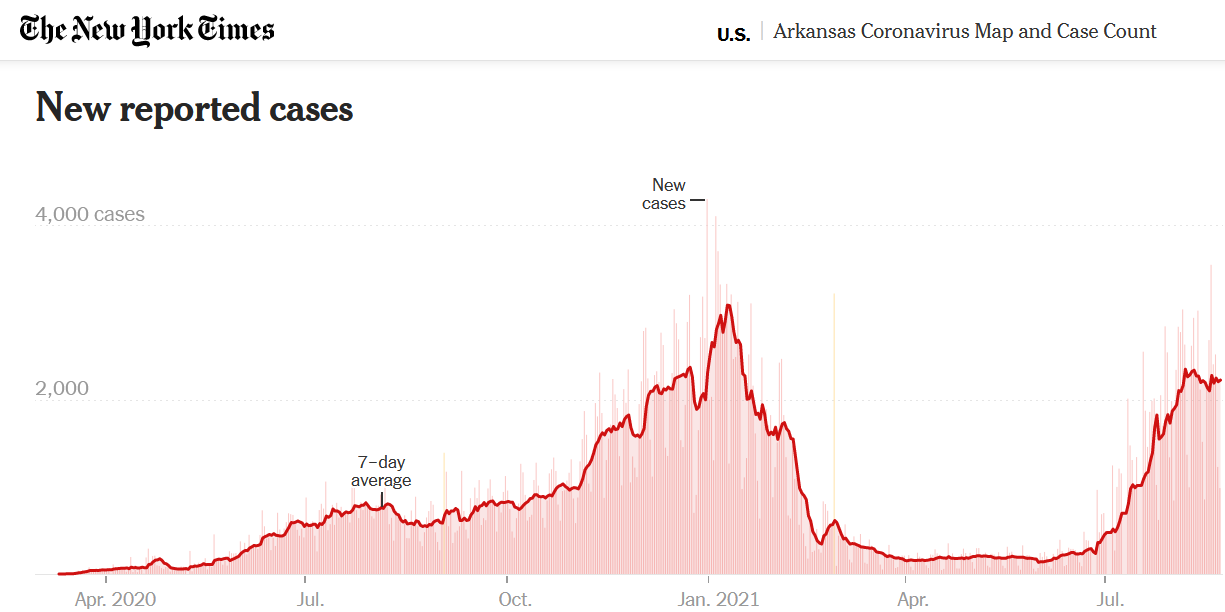

Tyson’s corporate headquarters are located in Springdale, Arkansas, in the northwest corner of the state. The region is a hotspot within a hotspot, as graphs from the New York Times show. Here’s what the state of Arkansas’s case trend looked like as of 8/24/21:

And here’s where cases have occurred around the state since the pandemic began:

Those big bubbles in the northwest corner of the state? They’re right over heavily populated Springdale in Washington County, where Tyson’s headquarters are located, and surrounding areas that are home to many of the farms and plants that produce its chicken.

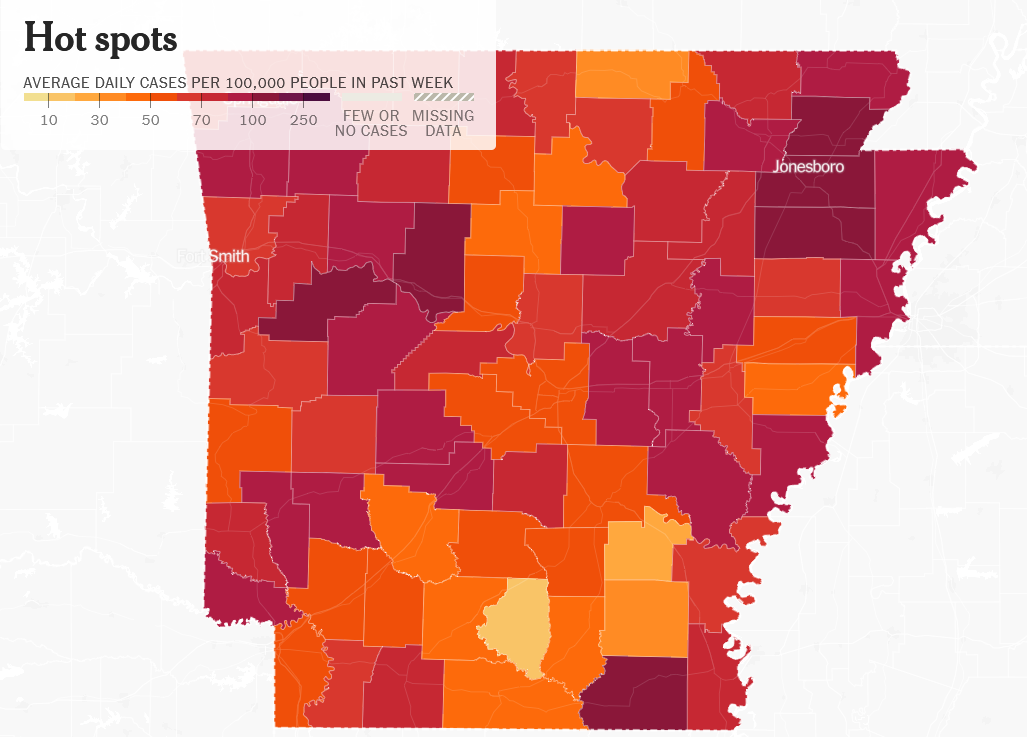

More recently, average daily cases in the state over the past week show that, while Washington County isn’t the state’s hottest hotspot, transmission is still far too high, averaging 88 cases per 100,000 people:

(For comparison, Pulaski County, Arkansas’s most heavily and densely populated county, home to the state capital Little Rock, had a case rate of 53 per 100,000 over the same week.)

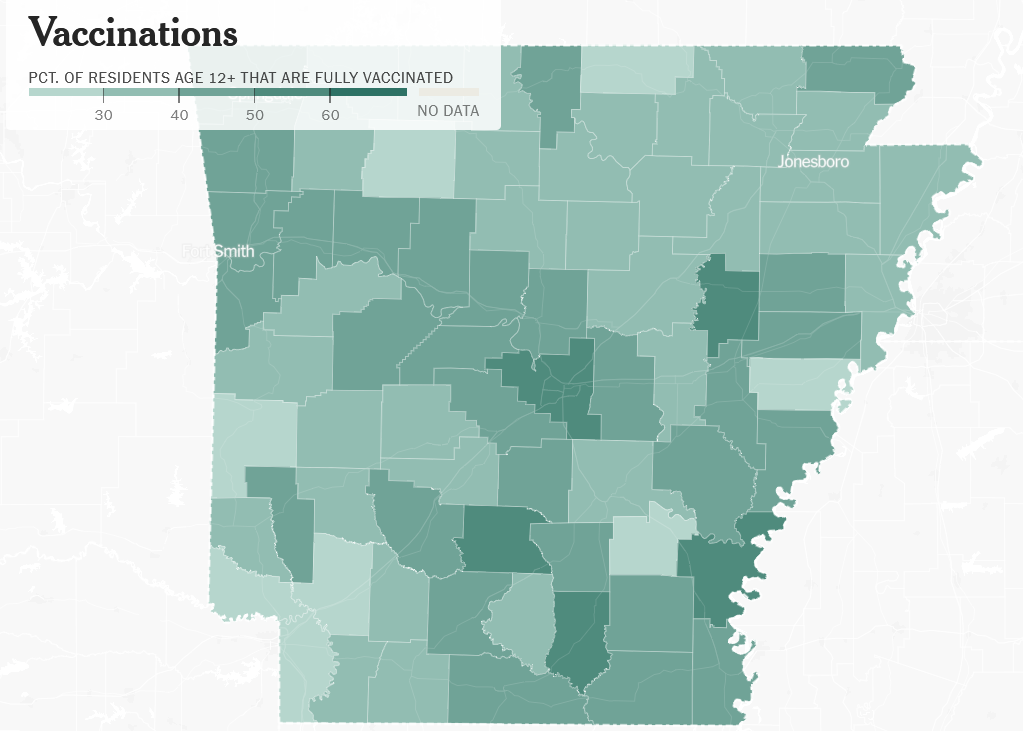

Meanwhile, vaccination rates across Arkansas trail the national average: just 40 percent of Arkansans are fully vaccinated compared to 52 percent nationwide, and the numbers are no higher in Washington and Benton counties in the northwest corner of the state:

If Tyson were really such a good neighbor, could it have done more all along to get shots into arms and prevent further spread in its neighborhoods, as some large corporations have done?

Tyson’s 2020 COVID response was abysmal

But of course, Tyson isn’t a good neighbor, or a good employer. I’ve written previously about the company’s shameful behavior during the early months of the pandemic in 2020—the lobbying, the lies, and the lack of protective equipment, social distancing, and sick leave for its workers. As meat and poultry processing plants turned into COVID-19 hotspots, Tyson came to lead the industry in a new and terrible way: more than 12,500 COVID-19 cases and 39 deaths had been reported among Tyson workers nationwide as of August 13, 2021, by far the most in the industry.

Yet by June of 2020, with the first wave of the virus still washing over the country, Tyson had already reinstated its policy of penalizing workers for staying home sick.

Does Tyson see its profits at risk?

Now here we are in a Delta-fueled fourth COVID wave, and in states with low vaccination rates, it’s proving worse than the third. Like many employers offering low-paying, high-risk work under these conditions, Tyson is having trouble keeping staff. The company’s CEO blames viral mutation for its hiring woes, saying recently, “We were on a good trajectory and then the Delta variant showed up.”

But really, who can blame people for not wanting to work shoulder-to-shoulder, during yet another viral surge, for a company that has already seen so many COVID cases and deaths among its employees?

Still, rising COVID rates in communities where it operates are bad for business. And even though Tyson’s third-quarter profits were up 42 percent over last year, it’s never enough. Moreover, the company may see a recent merger among two competitors in the (already hyper-consolidated) chicken market as a challenge. It’s hard to see Tyson’s vaccination pledge as anything but a cynical effort to protect the company’s bottom line. Staving off future losses in the form of worker sickness and death seems to be the real reason for Tyson’s new interest in limiting the impact of a disease it has previously allowed to spread like wildfire in its facilities.

In response to questions from my team in late July about vaccinations among its workforce, a Tyson spokesman emailed to tout the company’s efforts—Tyson, he said, has hosted more than 100 employee vaccination events and spent more than $700 million “related to COVID-19” (whatever that means). The spokesperson also claimed that “[t]he number of active Covid cases among our U.S. team members remains very low.” Of course, it’s also anyone’s guess what “very low” means. If the company is required to report such cases at all—the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA’s) requirements seem designed to minimize reporting—those numbers don’t appear to be publicly available.

Just a few days after our email exchange, Tyson announced it would mandate vaccination for all its workers by November 1, and more recently it has begun offering raffle-style incentives for reluctant workers. But is it too little, too late? Or worse, is it just a PR stunt?

Ultimately, even genuine, well-intended corporate actions aren’t enough to stop the spread of this virus in high-risk work environments like Tyson’s processing plants and the communities that surround them. What is really needed, as the advocates have long urged, is emergency OSHA action to safeguard worker health and safety by mandating more and better protective equipment, slower line speeds to allow more distancing, and sick time to keep infected employees from spreading the virus at work. OSHA failed to deliver such protections earlier this year, omitting meat and poultry workers from its COVID-19 emergency temporary standard and providing unenforceable guidance for the industry instead.

So while Tyson offers spin, its workers, their families, and their communities are still waiting for real protection.