The cold weather has pushed demand for energy very high. In our energy markets, demand rising faster than supply translates into higher prices. Electricity prices in the Mid-Atlantic and natural gas in the Northeast are showing this today, and this isn’t new or unique. Supplies to meet demand are limited by the capacity of the delivery systems.

While this shortfall can be seen in higher prices for natural gas and electricity, these higher prices are not just an energy market issue. These shortages are a threat to the reliability of the electric system.

Gas boom, are you there?

There is a boom in U.S. natural gas production, but that does not get the gas to markets. Natural gas delivery is limited by the capacity of the pipelines that move gas from production areas to consumers. The supply and demand for natural gas has outstripped the infrastructure to deliver. Electricity generating plants would like to have more gas, but all that gas isn’t available. In the current market system, electric generators using natural gas are counted on to run when needed to supply electricity, even if they have not made arrangements for a firm supply of their fuel. Without access to fuel at reasonable prices, the generators won’t run. And we are seeing that in the cold weather.

The electricity transmission lines, the natural gas pipelines, even the oil pipelines are always slower to expand than the potential for energy production. This is a problem that has plagued the development of wind energy for years. Because wind farms, like any large power plant, need transmission wires to connect to customers, there can be no wind farm built if there is no transmission. But in many remote areas, there has been no reason to build transmission. In this way, building wind farms where it is windy is held back by the lack of transmission to those production areas. With wind, it is a “which comes first, the chicken or the egg?” kind of problem.

The electricity sector, and the wind farm development in this country, has been slower and more cautious than the natural gas industry when it comes to building generation and using temporarily uncommitted capacity for transmission. Without access to transmission, wind farms don’t get built. That is not how it happens for the gas-fired plants that are built, expected to run by the reliability coordinators, but did not make the expenditures to secure gas pipeline capacity.

Windy and cold

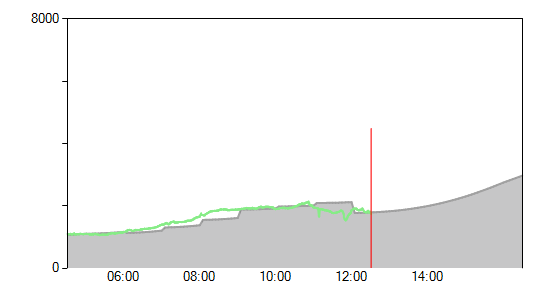

The cold weather performance of wind power this winter has been impressive. As I write, the PJM powerpool, stretching from Chicago to Virginia, is receiving the equivalent of a nuclear power plant’s worth of power from wind. A summary of earlier performance can be seen in a fine blog by Michael Goggin at the American Wind Energy Association.

Waiting for space on the wire

The expansion of wind to meet energy demands is waiting for the expansion of the transmission system. A variety of policies and sometimes even a poorly done study can limit how much transmission is planned and built for wind. A few recent examples of inadequate transmission planning for wind show that the planning process has been hamstrung.

- In the Eastern U.S.-wide planning effort run with state regulators and the U.S. Department of Energy, the transmission planning effort did not make a comparison of the savings on fuel over the lifetime of the assets from a large wind build-out, and instead just compared the cost of the transmission to one year’s fuel savings. (See this summary from Allison Clements, Project for Sustainable FERC.)

- The governor of Vermont asked why Vermont’s newest wind farm was curtailed during the July 2013 heat wave. The New England system operator explained that existing transmission was inadequate, and that the transmission planning does not anticipate building all the transmission necessary to make maximum use of that wind farm.

- A survey of transmission operators completed in 2010 shows that curtailing wind is a regular practice across the U.S., reflecting the standard planning assumptions that the transmission system need not be built to accommodate all of the energy that a wind farm can produce.

We have a long way to go to make the energy supply clean, renewable, and reliable. When the weather stresses the system, and exposes the assumptions and shortcuts, we can see what needs to be done. This is a specialized effort. It is the work I do at UCS. You can help support this work by joining as a member.