A rare event occurred this past weekend when two tropical systems approached the state of Hawaii. Hurricanes happen only occasionally in this part of the world because a fairly constant high pressure system deflects most of the storms. Also, the waters around Hawaii are typically cooler than tropical systems need in order to maintain their strength.

Hurricane Iselle made landfall Thursday night over the Big Island as a strong tropical storm (sustained winds of 60 mph), while Hurricane Julio passed safely to the north of the islands. It has been 22 years since the last direct hit. Last time, it was Hurricane Iniki, which hit the island of Kaua’i as a Category 4 storm.

The role of natural variability

In August 1992, Hurricane Andrew struck south Florida as a Category 5 hurricane. I was only a child then, but I convinced my family to drive away from our New Orleans home when Andrew turned towards Louisiana. A few weeks later I heard of another storm: Hurricane Iniki. It was a Category 4 storm and headed for the coast. I thought we might need to leave again until I saw where the storm was. It wasn’t in the Atlantic. It was in the Central Pacific and would hit Hawaii.

Iniki occurred during a fairly strong El Niño, which warmed the waters of the central Pacific and contributed to its formation. The same is the case this year. An El Niño had been forming (although it is currently shifting to neutral conditions) and the waters near Hawaii are warmer as a result. The high pressure center that usually protects Hawaii is also further north.

The role of El Niño on Hawaii hurricanes requires some basic knowledge about the location of sea surface temperature anomalies related to the phenomenon. The Niño 3 Region is bounded by 90°W-150°W and 5°S- 5°N. The Niño 3.4 Region is bounded by 120°W-170°W and 5°S- 5°N.

The role of climate change

We know El Niño is one of the main drivers for hurricane formation in the central Pacific (Niño Region 3.4), but the proximity of the two storms near Hawaii is highly anomalous. Did climate change have a role in the Hawaii hurricanes? According to experts the answer is no. This was a natural, albeit rare phenomenon. However, new research does suggest that more hurricanes will occur in the vicinity of Hawaii, including a recent study that shows a 3-4 fold increase in storms.

There is another way that climate change might be influencing weather systems in the Pacific. Usually, during an El Niño, the west Pacific (Niño 4) cools as warm waters move to the east Pacific (Niño 3, Niño 1+2). This year this has not been the case. The rains have not let up over the islands of the west Pacific and waters have continued to be warm.

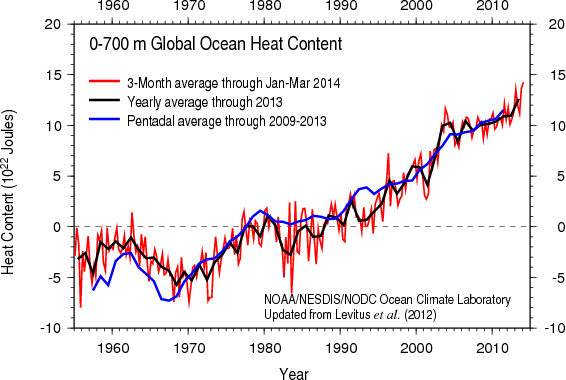

In fact, the ocean heat content of the west Pacific has remained high, hinting at a deeper pool of warm waters that has been continuously building due to strong easterly winds. These easterly winds are the same winds that have kept the tropical east Pacific cool and have contributed to a temporary speed bump in the rise of global surface temperatures.

New research suggests that the anomalous easterly winds, likely the reason for a cool east Pacific, might be due to the warming of the Atlantic Ocean. The faster warming of the Atlantic causes a difference in pressure with the Pacific, increasing the easterly winds. This is just one theory among many that describes the reason why the tropical east Pacific has been continuously cool even though the rest of the planet has warmed.

The research behind the cooling of the Pacific and the associated slowdown of the rise in global temperatures is an active area of climate science. However, the unabated rise in ocean heat content has shown us where global warming has gone: the oceans. Recent observations, such as the continuously warm west Pacific, are further proof how much heat can be trapped in the waters of our planet. And as the east Pacific warms again in the near future, global surface temperatures will likely see a sharp rise as well.