The science is clear. To limit the worst impacts of climate change, the US will need to cut CO2 and other heat-trapping emissions by at least 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, and achieve net zero emissions economy-wide no later than 2050. These targets are consistent with the Biden administration’s recent commitment to the Paris Agreement. Because of the key role the power sector will play in achieving these targets, federal policy makers provided specific instructions to include a Clean Electricity Payment Program (CEPP) in the Senate’s just-released federal budget resolution.

A CEPP is an investment program that would incentivize increasing shares of clean electricity by providing financial payments to utilities that procure a certain amount of clean electricity generation each year and charging penalties to utilities that fall short. The overall goal of a well-designed CEPP must be to achieve 80 percent of U.S. electricity generation from low or zero carbon energy sources by 2030. In this way, a CEPP could achieve a similar outcome as a so-called “clean” energy standard (CES), or renewable electricity standards (RES) that have been successfully implemented in multiple states.

A key policy design issue is whether generation from conventional natural gas power plants, as in those without any form of carbon capture and storage, should be eligible to receive partial payments or credits because they produce about half the smokestack CO2 emissions than coal power plants per unit of electricity. Providing incentives to build new gas power plants and pipelines, and continuing to allow upstream methane leakage when we need to achieve deep reductions in heat-trapping emissions in the next decade and beyond, are bad bets that are incompatible with our climate goals and would lead to major stranded assets and higher costs for consumers.

Here are 5 reasons why subsidizing gas under a CEPP is a bad idea:

1. Increasing gas use is incompatible with decarbonizing the power sector and broader economy

Recent deep decarbonization analyses project that most of the near-term reductions needed to meet economy-wide carbon reduction targets will come from the power sector because of the availability of low-cost alternatives like wind, solar, and energy efficiency to replace coal and gas.

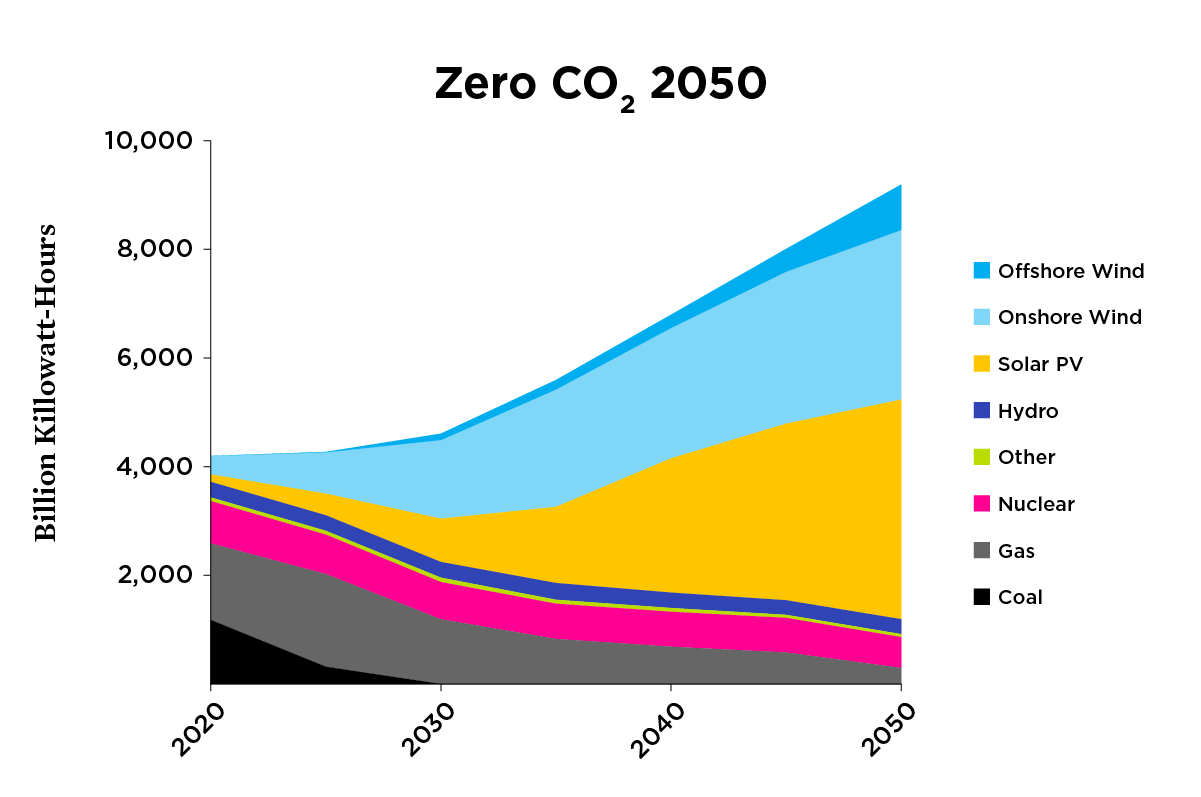

For example, a new UCS study released in July found that cutting U.S. power sector emissions 80 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 would be a key tool in meeting these broader economy-wide reduction targets. The power sector reductions were achieved by tripling renewable energy generation (primarily new wind and solar) from 20 percent US electricity generation in 2020 to nearly 60 percent in 2030, phasing out coal generation, and reducing gas generation from 40 percent in 2020 to 26 percent in 2030 (see Figure). Getting to 80 percent zero carbon would drive that level of gas generation even lower, and is a worthy target given the slow pace at which other necessary sectoral transitions have been advancing.

Our results are consistent with other recent decarbonization studies by Princeton, University of Maryland, and Evolved Energy Research. A recent UC Berkeley study that analyzed the impacts of a national CES of 80 percent by 2030 also found that gas generation would decline from 40 percent of US electricity generation in 2020 to 20 percent in 2030, and no new gas or other fossil plants would need to be built in the US in the next decade. All of the new generation needed to meet the CES targets and replace gas and coal generation was from wind and solar.

All these studies show we need to drive down gas generation by 2030 to meet power sector and economy-wide emission reduction targets. However, not allowing gas generation to get payments under an 80-percent-by-2030 CEPP does not mean we won’t have gas in the system. Gas could still maintain a market share of approximately 20 percent by 2030 if coal generation is mostly phased out by that time, and a larger share before that.

2. Gas is not low carbon

The extraction, distribution, and use of natural gas also results in the leakage of methane emissions that pose a major climate risk. Methane is more than 80 times more potent a global warming gas than CO2 in its first 20 years after release, and approximately 30 times greater over a 100-year period.

The gas and oil industry is the second largest source of methane emissions in the US after agriculture, representing 30 percent of total emissions in 2019 according to EPA. However, studies by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and hundreds of researchers found that the U.S. oil and gas industry leaks on average 2.3 percent of all the gas it produces, which is at least 60 percent higher than EPA’s estimate of 1.4 percent. A more recent EDF study found even higher leakage rates of 3.7 percent in the Permian Basin in West Texas and Southeastern New Mexico. While these leakage rates may sound small, previous EDF studies show that losses must be kept below 2.7 percent for gas power plants to have lower lifecycle emissions than coal.

Accounting for upstream methane emissions as part of the policy design is vitally important to avoid unintended consequences. If the program accounted for the full lifecycle emissions of gas, then its carbon reduction benefits compared to coal could evaporate entirely.

3. Gas is not clean

Gas has its own set of environmental, public health, and safety issues to contend with. For example, gas power plants release nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions that cause respiratory problems and react with other substances to produce particulate matter and ozone, which contribute to asthma, heart attacks, and even premature death. To make matters worse, many gas power plants are often located in or near low-income communities and communities of color that are already overburdened with pollution. For example, more than half of all gas power plants in California are concentrated in disadvantaged communities.

Hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” of natural gas, which involves injecting millions of gallons of water and toxic chemicals at high pressure into shale formations, can also result in significant environmental and public health impacts on local communities. This can include air pollution from truck traffic, increases in water use and contamination from toxic chemicals and wastewater leaking into groundwater, and even earthquakes. Methane leakage from pipelines is also a major safety issue that can result in loss of life and property from explosions.

Providing payments for gas generation under a CEPP would only exacerbate these problems.

4. Stranded assets and higher costs for consumers

Providing incentives to build new gas power plants and pipelines under a CEPP when we need to achieve deep reductions in heat-trapping emissions could lead to major stranded assets and higher costs for consumers. In fact, a rush to gas has already occurred with more than 120,000 MW of new gas-fired capacity added between 2008 and 2018, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence. This resulted in utility capital expenditures on gas power plants and pipelines rising from just over $60 billion in 2008 to more than $120 billion in 2019.

A new S&P analysis shows that meeting ambitious decarbonization targets such as those included in the Biden Administration’s proposed clean energy standard could result in $34 billion in stranded investments in new gas plants and another $34 billion in stranded coal plant assets.

A 2019 study by RMI found that clean energy portfolios—combinations of renewables, storage, and demand-side management—are projected to be cheaper than 90 percent of proposed gas combined cycle plants and 60 percent of new combustion turbine capacity by 2035. They estimated $90 billion of planned investment in new gas-fired power plants and over $30 billion of planned investment in interstate gas pipelines could be stranded. However, if clean energy replaces the proposed gas plants, they found consumers could save $29 billion.

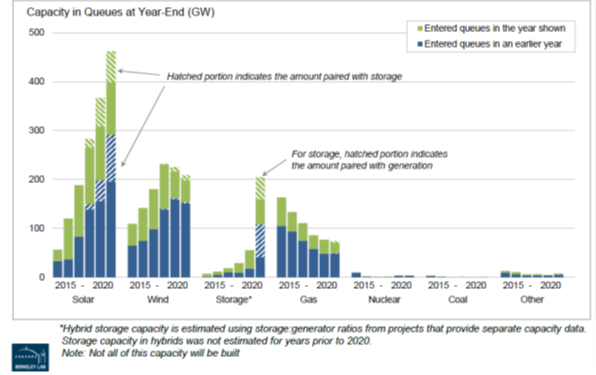

Recent data from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory also highlights the eroding economics of gas power plants, as reflected in the steady decline of gas capacity and the significant increase in solar, wind, and storage capacity in regional transmission interconnection queues over the past 5 years (see Figure). Gas capacity has declined from more than 150 GW in 2015 to 74 GW in 2020, while solar capacity has grown by a factor of nine to 462 GW, wind capacity has more than doubled to 209 GW, and storage capacity has exploded to 200 GW in 2020. While much of the capacity in interconnection queues will not ultimately be built, it clearly illustrates the economic shift away from gas to renewables.

5. Studies showing that partial crediting for gas will accelerate coal retirements are flawed

Some studies have suggested that allowing partial crediting for gas in CES could help accelerate fuel switching from coal to gas that not only reduces CO2 emissions but also criteria pollutants, resulting in public health benefits.

There is no question that coal has to be rapidly removed from the system. But these studies have several important limitations. First, most of these studies use models that don’t consider upstream methane emissions and other environmental and public health impacts described above from drilling and transporting gas.

Second, most models assume perfectly rational economic decision making and don’t consider various market failures that result in real-world behavior diverging from modeled findings. For example, the practice of “self-committing” allows coal plant owners to operate their plants uneconomically in wholesale markets when lower cost alternatives are available. A 2018 UCS analysis shows that this market distortion is resulting in $1 billion per year in increased costs for consumers across four major US power markets—PJM, MISO, SPP, and ERCOT. Market distortions like this should give policy makers and regulators great pause when considering giving gas-fired power payments under a CEPP.

Many coal plants also have long-term coal contracts that can be a market barrier to retiring and replacing them with gas or other alternatives that aren’t typically captured in models.

Coal-fired and gas-fired power plants and gas pipelines owned by regulated utilities are typically allowed by state PUCs to get cost recovery and a return on investment from ratepayers even if they are more expensive to operate than other alternatives. Most coal and gas plants owned by co-ops or municipal utilities also have approval from their boards to recover these above-market costs from ratepayers.

When these and other factors are considered, providing payments for gas plants under a CEPP could result simply result in windfall profits to the gas industry, and tip the scales away from investing in cleaner low-cost alternatives such as efficiency, renewables, and energy storage.

Coal has to go, but subsidizing gas is the wrong way to achieve it

It’s clear that coal needs to be phased out in the next decade, with proactive investments in a fair transition for coal workers and coal-dependent communities. But incentivizing conventional gas generation under a CEPP is the wrong way to do it. Other policies and regulations will be needed, and would be more effective in driving coal plant retirements–such as implementing stronger EPA regulations, ending the practice of self-commitment, requiring coal plant owners to renegotiate long-term coal contracts, securitization of outstanding coal plant debt, and debt forgiveness for co-op owned coal plants.

Unnecessarily giving natural gas a boost–with all its attendant climate, environmental, health, and economic harms–is not the way to go.