On March 28th, North Korea unveiled a new type of nuclear warhead—a smaller, more compact tactical warhead with battlefield advantages. The news comes days after North Korea unveiled an underwater attack drone it says is capable of generating a “radioactive tsunami.”

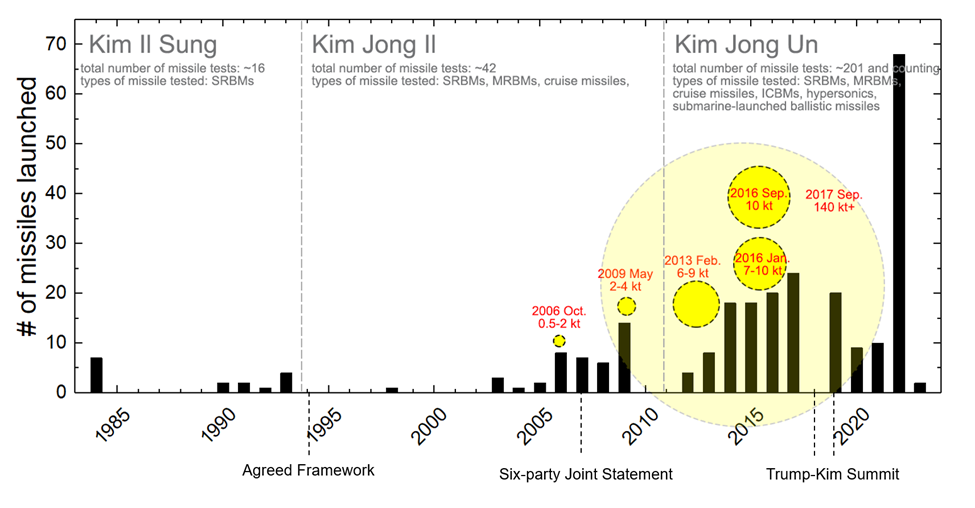

North Korea continues to conduct military exercises. Last year alone, it tested 70 missiles, including short-, medium- and long-range missiles. The year 2022 saw more missile tests from North Korea than at any time in its history. North Korea is expanding its nuclear arsenals in both quantity and quality—increasing the number while modernizing and diversifying the types of weapons and delivery vehicles. This includes the development of a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), which North Korea successfully test-fired in November 2022.

The increasing threat is influencing South Korean domestic politics, with President Yoon publicly declaring South Korea may consider the option to build its own nuclear weapons. The sentiment is fueled by concerns that Washington may not protect Seoul if that protection risks a North Korean nuclear attack. Yoon’s remark was later retracted, announcing that Seoul’s realistic option is to respect the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime. But if the threat from North Korea continues to grow, South Korea may consider the question again.

And now, experts and analysts suggest that North Korea appears to have completed preparations for its next nuclear test.

A history of North Korean nuclear tests

North Korea conducted six explosive nuclear tests between 2006 and 2017. The most recent test generated the largest explosive yield. The test was estimated to have released at least 140 kilotons of energy, approximately 7-10 times more than the bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. North Korea claimed the test was a hydrogen bomb, a more advanced type of weapon that uses nuclear fusion as well as fission to create a more powerful explosion. If a 140 kt nuclear weapon is dropped on the heart of Seoul, more than 200,000 people will likely die, with almost three times as many injured.

North Korea’s nuclear tests were conducted at the Punggye-ri test site, which had been announced as “destroyed” in 2018 when it decided that it had successfully verified its nuclear capabilities. Analysis of satellite imagery shows limited activity at this site between the fall of 2018 and the spring of 2022. But in early 2022, signs of renovation were observed. In September 2022, IAEA chief Rafael Grossi noted that North Korea’s nuclear test site was reopened. Soon after, Yoon assessed that North Korea had completed preparations for its seventh nuclear test.

If North Korea had satisfactorily verified its nuclear capabilities as it claimed in 2017, is further testing driven predominantly by political or technical motivations?

The technical purpose of a nuclear test– could it be a tactical nuclear weapon?

North Korea has been modernizing its nuclear arsenal, including the development of short-range, guided missiles described as being designed to launch tactical nuclear weapons, which it started testing merely three months after the end of the Hanoi Summit in 2019. In January 2021, at the Eighth Worker’s Party Congress—a high-level meeting in which rulers discuss the agenda for the future, Kim confirmed North Korea’s development of tactical nuclear weapons, declaring that the regime has a successful program to “miniaturize, lighten, and standardize nuclear weapons to make them tactical ones.” Tactical nuclear weapons are designed for battlefield advantage, to be used rather than to support nuclear deterrence.

North Korea’s tactical nuclear weapons development could include low-yield nuclear weapons targeted at a specific site, such as the military base Camp Humphreys—America’s largest overseas military base 40 miles south of Seoul. Low-yield weapons, typically less than 10 kt in energy release, could minimize collateral damage, lowering the threshold for escalation (in hopes of curtailing a strong response from Washington and Seoul), while still weakening military bases. An order of magnitude smaller than most deployed strategic nuclear weapons, 10 kt still represents a significant nuclear yield. By comparison, the yields for Little Boy and Fat Man, used by the United States in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, were estimated at 15 and 21 kt.

While North Korea has demonstrated the ability to build powerful nuclear weapons that can be carried by its powerful intercontinental-range missiles, it may now want to refine its designs to build more compact, lighter, less powerful weapons that could be carried on these shorter-range missiles. Observations of past nuclear and missile tests suggest that North Korea can mount nuclear warheads on existing short-range or medium-range missiles. But successful field deployment of tactical nuclear weapons carried by solid-fueled ballistic missiles or missiles that can be launched in close succession by large multiple-rocket launchers, may require additional explosive nuclear testing alongside simulations. A September 2022 report by South Korea’s Institute for National Security Strategy speculated that the explosive nuclear test could involve North Korea’s new tactical weapon of less than 300 kg in weight, and 60 cm in diameter, to evaluate the success of its nuclear arsenal miniaturization.

But this does not mean that North Korea’s nuclear testing is limited to tactical nuclear arsenals. Kim Jung Un also commented on his pursuit of “super-large” nuclear warheads. North Korea might instead want to conduct a test with large explosive detonators to increase certainty in its existing technical capabilities. Olli Heinonen, a former director of the IAEA and a distinguished fellow at the Stimson Center, told Voice of America that “it is likely that they need several tests to meet the requirements of their ambitious nuclear weapons program, which has tactical nuclear weapons, intermediate range, and intercontinental ballistic missiles. They have probably more than one type of nuclear warhead, which all need to be tested.”

Political purpose – what message is it trying to send?

In addition to the technical purpose, there may be political reasons behind North Korea’s swift weapons development and nuclear testing.

On the international front, North Korea is enhancing its deterrent capability and demonstrating its ability to take pre-emptive measures against adversaries. In September 2022, North Korea legislated the conditions for preemptive nuclear use, legalizing the use of nuclear weapons preemptively to strike against adversaries. The evolving doctrine suggests that North Korea is lowering the threshold to use nuclear weapons while drawing a clear line that there is ”no bargaining” over its nuclear weapons, and it will not denuclearize even if it faced 100 years of sanctions.

North Korea continues to strengthen deterrence by upgrading its nuclear forces. By perfecting its nuclear capabilities, North Korea is exhibiting its determination to continue its nuclear weapons program, sending a message of its growing nuclear prowess and further establishing itself as a nuclear weapons state. But if North Korea conducts another test, it could consider using aspects of its nuclear program as leverage in negotiations.

Skepticism remains that North Korea would want to enter any negotiation with the United States. Washington already said it is open to dialogue with North Korea without any preconditions, yet North Korea has only responded with more missile tests. Some analysts claim that North Korea might seek its own path around sanctions through economic cooperation with China and Russia, taking advantage of the currently hostile US-Sino relationship.

Domestically, North Korea’s nuclear test might also serve to strengthen internal solidarity amid all the domestic problems: COVID-19, food shortages, and natural disasters.

When is it happening?

Any day now is what many South Korean and US intelligence authorities say about North Korea’s next nuclear test. Indeed, North Korea might see an advantage in doing so in today’s complex geopolitical environment. Russia’s war on Ukraine is casting doubts over the long-term future of nuclear nonproliferation; China and Russia are shielding North Korea from further UN sanctions; Russia has suspended its participation in New START and has announced it is ready to resume nuclear testing if the United States does; and the attention of the United States is focused on Russia and China—all of which provide significant distraction which Pyongyang may hope to capitalize upon.

But a nuclear test is not cheap, either geopolitically or materially. Making nuclear weapons takes time and resources, especially with a limited fissile materials stockpile and limited availability of domestic nuclear materials, which might be used for weapons instead. These limits create important bounds on the number of nuclear tests that North Korea will be prepared to undertake. It’s possible that North Korea will not do an explosive test at all.

The size of the original image used as the feature image for this blog was modified under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.