The last few days have been difficult for people in Houston. Though they have been difficult for everybody, the environmental justice communities like Manchester and Galena Park in eastern Houston are now facing a double whammy of climate change and toxic contamination.

Adding to the toll of human suffering, death, loss of livelihoods, and dislocation that Hurricane Harvey is leaving in its wake, environmental justice communities in Houston are now facing threats from the many petrochemical facilities that already expose them to acute and chronic air toxics emissions. Over the last few days, members of the community have been sending out reports of (worse than usual) smells, itchy throats and eyes. And there are already reports of chemical spills in the area.

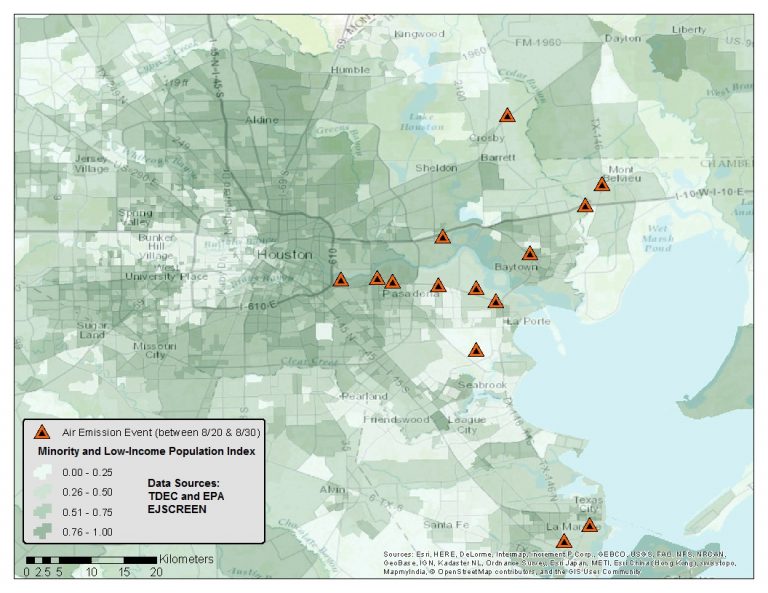

In preparation for Hurricane Harvey, many petrochemical companies performed controlled shutdowns of many facilities, releasing large amounts of contaminants to the air, including benzene, toluene, carbon monoxide, butane, nitrogen oxide, ethylene, and other toxics. In other cases, tank rooftops and other structures collapsed due to the heavy rains. Many of these acute air pollution events occurred along the Pasadena Freeway where many of the most vulnerable populations in Houston live (but many other shutdowns and malfunctions were reported in Goldsmith and Old Ocean).

The map below shows facility incidents reported to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s Air Emissions Event Reporting database for August 20-29, 2017. The incidents in this map were due to planned shutdowns and other contingencies related to Hurricane Harvey. For example, a roof in the Exxon Mobil refinery in Baytown collapsed due to excess rain, and the company estimated that around 12,000 pounds of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were emitted into the air.

If this wasn’t an already dire set of hazardous circumstances, threats such as those from the likely explosion of the Arkema plant that manufactures and stores the very volatile compound organic peroxide endangers the lives of Houston area residents. It’s already well known that low-income communities of color are more likely to live near facilities that process or store highly hazardous chemicals. It’s no wonder then that environmental justice advocates have correctly characterized the Hurricane Harvey disaster as the outcome of extreme weather fueled by climate change, failed chemical safety policies, and hazardous petrochemical facilities that have left Houston residents swimming in a “toxic soup.”

Which begs the question—why are there no protections for these communities? It’s not due to lack of information or knowledge about these threats. The evidence is clear that climate change is making storms stronger. It’s also clear that low-income communities of color in Houston and elsewhere are more exposed to toxics from the petrochemical industry. We know because the Union of Concerned Scientists partnered with the environmental justice community in Houston to document the disproportionate burden of toxics in their communities.

EPA scientists also know how industries that manufacture, process, or store dangerous chemicals can be more transparent in publicly sharing information on chemical inventories, improve accident prevention plans, data management, and federal coordination. But the Trump administration continues to sideline federal science by delaying the implementation of amendments to the Risk Management Program (RMP) Rule.

The Arkema facility is a case in point, as it is one of many facilities that under the now-delayed RMP amendments would have had to research safer technologies and chemicals to limit the effect of a disaster or explosion on surrounding communities and workers. The RMP rule would have also required this facility to begin coordinating with local emergency responders to make sure they have necessary information before heading into a volatile facility.

It is long past time for communities near industrial facilities to receive the justice they deserve. Industry must be responsible for their action, or too often inaction. And governments at all levels from local to federal must ensure that all companies follow the rules and are held accountable for the damage they do, not just when a storm occurs, but every day. No more excuses.

Want to help?

Donate directly to Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (t.e.j.a.s.), an Environmental Justice organization in Houston in the frontline of Hurricane Harvey, toxics, and climate change.