The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) sent a special inspection team to the Indian Point Energy Center in New York after an electrical transformer on Unit 3 exploded and burned. But the NRC team was not investigating the cause and effect of the transformer’s problem—they were examining how water flooded the room housing the electrical distribution panels. Had the flooding not been discovered and stopped in time, the panels could have been submerged and disabled, plunging Unit 3 into a station blackout condition like the one that caused disaster at Fukushima four years earlier. The NRC’s team documented that flooding has been a recurring problem at Indian Point and that a cost-effective fix identified years ago that would reduce the chances of core meltdown by nearly 20 percent remains on the shelf instead of installed in the plant.

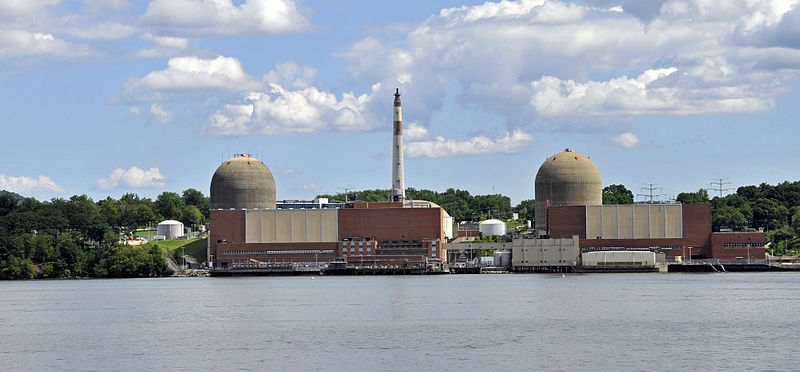

Indian Point (Source: Tony on Creative Commons)

How the Event Unfolded

On May 9, 2015, one of the transformers at the Indian Point nuclear power station in New York exploded, leading to a fire and activating the fire protection system. The fire was extinguished but water pooled on the floor of the switchgear room, where electricity is transmitted to the emergency systems. If the water level were to exceed five inches, the switchgears would be disabled, leading to a station blackout and thereby increasing the risk of a nuclear meltdown. Fortunately, the water level remained well below this threshold.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) sent a Special Inspection Team to determine water pooled on the floor of the switchgear room, the potential risk it posed, and how workers responded to this threat.

The NRC team determined that valves in the switchgear room that opened to spray water on the transformer fire malfunctioned because parts were corroded and clogged with debris. The valves leaked water into the room. The drain in the floor was also partially blocked by debris, allowing the room to begin flooding. The periodic tests of the drain conducted by the plant owner were inadequate to reveal clogging problems, and while tests did reveal problems with the valve, workers did not follow up by fixing the valves. Thus, the plant owner repeatedly violated NRC regulations that require it to identify and fix safety problems in a timely and effective manner.

Moreover, the vulnerability of the electrical equipment in the switchgear room to internal flooding has been flagged repeatedly and never resolved.

UCS has prepared a more detailed and illustrated accounting of this near-miss.

NRC Sanctions

The NRC determined that the flooding was caused by a component that had malfunctioned when it was tested in March 2015, April 2013, and April 2011, and that repeatedly unfixed failure once again caused flooding during the May 2015 event. For repeatedly violating a federal regulation that requires owners to fix problems in a timely manner, the NRC issued a green finding, the least serious in its four color-coded sanction levels.

UCS Perspective

“No blood, no foul” may work in pick-up basketball and touch football games, but it has no place in nuclear safety. The NRC simply must take enforcement of federal safety regulations seriously. If not, the U.S. Congress must find some organization who will take this important job seriously before many Americans pay an unacceptably high price for nuclear nonchalance.

In 1988, the NRC required plant owners to evaluate their facilities for vulnerabilities to severe accidents that could lead to the release of radioactivity into the environment. In response, in 1994, the owner identified several scenarios in which water pouring from a broken pipe could flood the switchgear room and disable the electrical equipment. However, the NRC did not require that owners fix the vulnerabilities they identified. Thus, the owner of Indian Point addressed only some of these vulnerabilities.

In 2007, the owner of Indian Point submitted an application to the NRC for a 20-year operating license extension. As part of this process, the NRC requires the owner to conduct an evaluation of Severe Accident Mitigating Alternatives (SAMAs)—modifications to the plant and revisions to procedures that would lessen the chances and/or consequences of severe accidents. The owner found that installing a flood alarm in the switchgear room that would alert the control room operators when the water reached a certain level would be cost beneficial. The cost of the $200,000 alarm would be more than offset by the expected benefit of $1.4 million or more. Yet the NRC does not require that cost-beneficial modifications be made unless they address a problem that is aging related. Because a flood alarm would address a problem that had been in existence since the reactor was built, the NRC did not require the owner to install this cost-beneficial safety upgrade.

Following the Fukushima accident, the NRC required owners to re-evaluate seismic and flooding hazards, but again did not require owners to make cost-beneficial modifications to address these hazards.

Thus, to address the vulnerability to flooding of the electrical equipment in the switchgear room—as well as other vulnerabilities identified by past assessments—the NRC must require that owners make cost-beneficial safety upgrades.

Identifying but not implementing cost-beneficial safety upgrades just makes it wicked easy for lawyers to win huge liability lawsuits after accidents. Defendants lack a reasonable answer to counsel for the plaintiff’s question, “why again did you decide not to install the cost-beneficial fix to this known safety problem?”

Featured photo: Patrick Stahl