The Grand Gulf Nuclear Station located about 20 miles south of Vicksburg, Mississippi is a boiling water reactor with a Mark III containment that was licensed to operate by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in November 1984. It recently set a dubious record.

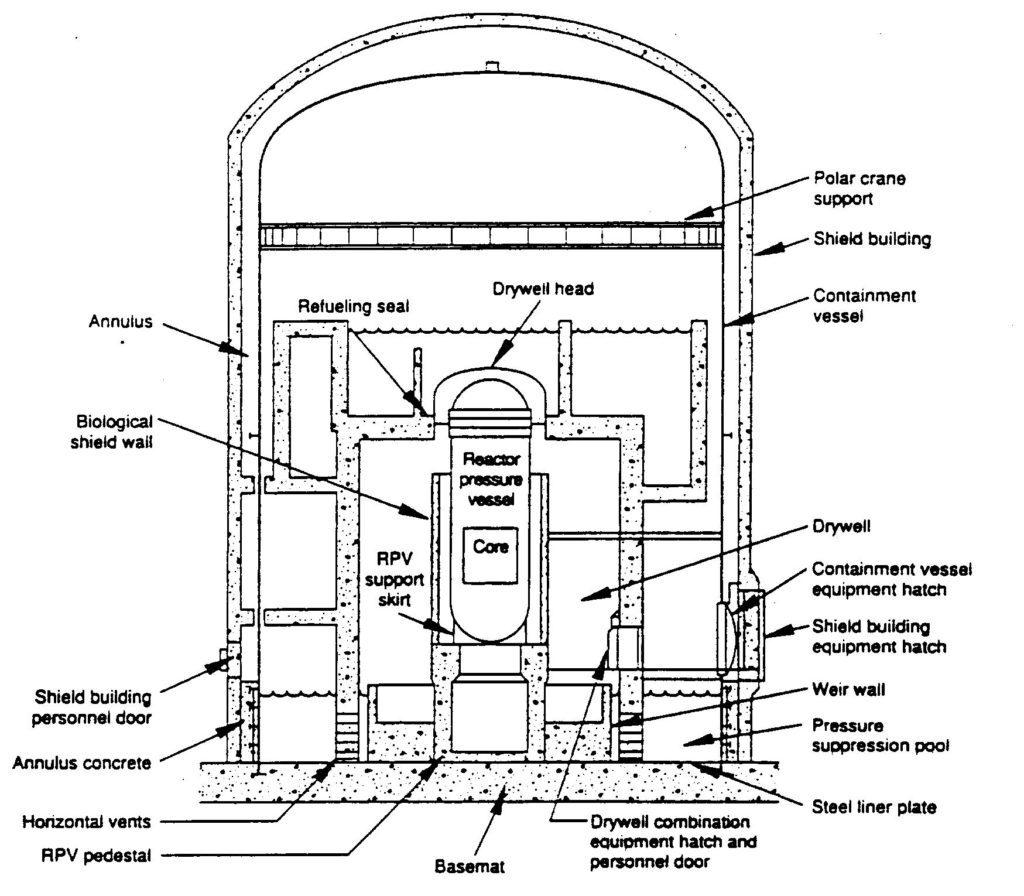

The Mark III containment is a pressure-suppression containment type. It features a large amount of water in its pressure suppression pool and upper containment pool. In case of an accident, energy released into containment gets absorbed by this water, thus lessening the pressurization of the atmosphere within containment. The “energy sponge” role allows the Mark III containment to be smaller, and less expensive, than the non-pressure suppression containment structure that would be needed to handle an accident.

Fig. 1 (Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission)

The emergency core cooling systems (ECCS) reside in a structure adjacent to the containment building. The ECCS for Grand Gulf consist of the high pressure core spray (HPCS) pump, the low pressure core spray (LPCS) pump, and three residual heat removal (RHR). The preferred source of water for the HPCS pump is the condensate storage tank (CST), although it can also draw water from the suppression pool within containment. The other ECCS pumps get their water from the suppression pool.

One of the RHR pumps (RHR Pump C) serves a single function, albeit an important one called the low pressure coolant injection (LPCI) function. When a large pipe connected to the reactor vessel breaks and drains cooling water rapidly from the vessel, RHR Pump C quickly provides a lot of water to replace the lost water and cool the reactor core.

The other two RHR pumps (RHR Pumps A and B) can perform safety functions in addition to the LPCI role. Each of these RHR pumps can be aligned to route water through a pair of heat exchangers. When in use, the heat exchangers cool down the RHR water.

RHR Pumps A and B can be used to cool the water within the reactor vessel. In what is called the shutdown cooling (SDC) mode, RHR Pump A or B takes water from the reactor vessel, routes this water through the pair of heat exchangers, and returns the cooled water to the reactor vessel.

Similarly, RHR Pumps A and B can use used to cool the water within the suppression pool. RHR Pump A or B draws water from the suppression pool, routes this water through the heat exchangers, and returns the cooled water to the suppression pool.

Finally, RHR Pumps A and B can be used to cool the atmosphere within the containment structure. RHR Pump A or B can take water from the suppression pool and discharge it through carwash styled sprinkler nozzles mounted to the inside surfaces of the containment’s upper walls and roof.

Fig. 2 (Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission)

Given the varied safety roles played by RHR Pumps A and B, the operating license for Grand Gulf only permits the reactor to continue running for up to 7 days when either pump is unavailable. Workers started the 7-day shutdown clock on August 22, 2017, after declaring RHR Pump A to be inoperable. The ECCS pumps are tested periodically to demonstrate their capabilities. RHR Pump A failed to operate within its design band during testing. The pump was supposed to be able to deliver at least a flow rate of 7,756 gallon per minute for a differential pressure of at least 131 pounds per square inch differential across the pump. The differential pressure was too low when the pump delivered the specified flow rate. A higher differential pressure was required to demonstrate that the pump could also supply the necessary flow rate under more challenging accident conditions.

Before the clock ran out, workers shut down the Grand Gulf reactor on August 29. Workers replaced RHR Pump A and restarted the reactor on October 1, 2017.

It is rare that a boiling water reactor has to shut down for a month or longer to replace a broken RHR pump. The last time it happened in the United States was a year ago. Workers shut down the reactor on September 8, 2016, after an RHR pump failed testing on September 4. The RHR pump was unable to achieve the specified differential pressure and flow rate at the same time. Workers could throttle valves to satisfy the differential pressure criterion, but the flow rate was too low. Or, workers could reposition the throttle valves to obtain the specified flow rate, but the differential pressure was too low. The RHR pump was replaced and the reactor restarted on January 29, 2017.

The reactor—Grand Gulf.

The failed pump—RHR Pump A.

The “solution”—replace the failed pump.

UCS Perspective

Grand Gulf has experienced two failures and subsequent replacements of RHR Pump since the summer of 2016. That’s two more RHR pump replacements than the rest of the U.S. boiling water reactor fleet tallied during the same period. Call Guinness—Grand Gulf may have broken the world record for most RHR pump broken in a year!

Records are made to be broken, not RHR pumps.

The company’s report to the NRC about the most recent RHR Pump A failure dutifully noted that the same pump had failed and been replaced a year earlier, but claimed that corrective action could not have prevented this year’s failure of the pump. Maybe the same RHR pump broken twice within a year for two entirely unrelated reasons. The Easter bunny, the tooth fairy, and Santa Claus all agree that it’s at least possible.

On October 31, 2016, the NRC announced it was sending a special inspection team to Grand Gulf to investigate the failure of RHR Pump A and other problems. The NRC’s press release concluded with this sentence: “An inspection report documenting the team’s findings will be publicly available within 45 days of the end of the inspection.”

As of October 24, 2017, no such inspection report has been made publicly available. Call Guinness—the NRC may have broken the world record for the longest special inspection ever!

Grand Gulf was restarted on January 29, 2017, 90 days after the NRC announced it was sending a special inspection team to investigate a series of safety problems. The inspection report should have been publicly available as promised to allay public concerns that the numerous safety problems that caused Grand Gulf to remain shut down for four months had been fixed.

On June 29, 2017—241 days after the NRC announced the special inspection report—I emailed the NRC’s Executive Director for Operations inquiring about the status of this overdue report.

On October 2, 2017—95 days after my inquiry—the NRC’s Executive Director for Operations emailed me a response. He indicated that the onsite portion of the special inspection was completed on November 4, 2016, and that the inspection report “should be issued within the next few weeks.”

The NRC promised to issue the special inspection report around December 19, 2016, when the inspection ended.

The NRC promises to value transparency.

The NRC should either stop making promises or start delivering results. Promises aren’t made to be broken, either. That’s what RHR pumps are for, at least in Mississippi.

Fig. 3 (Source: Kaja Bilek Flickr photo)