After decades of dragging its feet on the issue, the FDA has finally acknowledged that the ongoing massive use of antibiotics in food animal production poses a public health risk that demands a response. Such use, which is endemic in American agriculture, leads to the emergence of human and animal diseases that are impervious to antibiotics and increasingly expensive and difficult to treat.

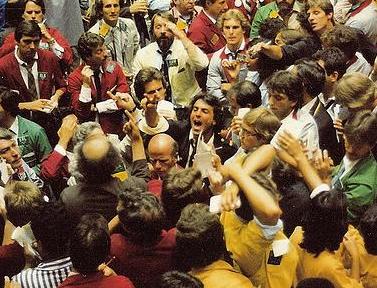

Under the FDA’s new antibiotics policy, drug approval negotiations will resemble the trading floor of a stock market. (Pictured: Chicago Mercantile Exchange, summer 1982.)

Photo courtesy of MojoBaer via Flickr.

The FDA’s policy

The FDA’s approach to this public health crisis is to eliminate unacceptable (“injudicious”) uses of antibiotics, and subject the rest to veterinary oversight through either prescriptions or veterinary feed directives (VFDs).

The agency has deemed so-called production uses of antibiotics, like feed efficiency and growth promotion, as unacceptable and all health-related uses (therapy, disease control and disease prevention) as acceptable. The approach sounds reasonable but has hidden flaws.

Production uses are unacceptable because efficient production can be achieved by good husbandry without risking the efficacy of valuable antibiotic drugs. In addition production uses typically involve the administration of drugs at low doses for months at a time, the perfect recipe for encouraging the emergence of resistant bacteria in livestock and poultry.

Health-related uses that are considered acceptable, on the other hand, are a mixed bag.

Therapy, the treatment of sick animal to cure illness and prevent suffering is generally acceptable. Animals get sick only sporadically and when the do are usually treated at high doses for a relatively short period of time.

By contrast, most routine antibiotic uses for prevention involve the same long durations of administration at low doses as production use and good husbandry can prevent disease as effectively as drugs. So long term, routine preventive uses of antibiotics are unacceptable.

There are special circumstances where preventive uses are acceptable. That’s where antibiotics are necessary to prevent imminent occurrence of disease. Disease outbreaks occur relatively rarely and involve relatively short term courses of treatment.

But the FDA policy does not separate out the large scale, routine preventive uses of antibiotics from therapy and special preventive uses in cases of imminent danger. As will be discussed below, lumping all health–related uses together as acceptable sets the stage for large scale waste of agency resources with virtually no public health benefit.

The voluntary path

As noted above, the FDA’s policy is to eliminate all production approvals for feed efficiency and growth promotion. Over 20 companies currently hold such approvals, legally known as label claims. Typically, these claims appear on a drug label and indicate that the drug can be used in a particular way (by injection, by feed), in a particular animal species (swine, turkeys), at a particular dose, and for a specified purpose (to treat, prevent or control a specific disease or improve production).

The Agency can legally withdraw the label claims approvals if it can show that uses under the label circumstances are no longer safe in terms of resistance.

A second way to eliminate production approvals is somehow to persuade all the drug companies to drop claims voluntarily.

The trick, of course, is to get the drug companies to go along. Asking drug companies to no longer sell products on which they are making millions of dollars seems almost ridiculous.

The FDA knows that drug companies will not give up production claims out of altruistic concern for the public health. So it is planning to give them something in exchange: new label claims for drugs for disease prevention or therapy. Sales of drugs under the new claims would bolster sales of antibiotic products and repair any damage to bottom lines from the loss of the production claims.

The negotiations for new approvals

Although the trade-off idea is clear enough in concept, the negotiations to implement it will be complicated and could prove messy. The rules for conducting these negotiations are laid out in Draft Guidance For Industry #213 (hereinafter Guidance # 213).

The idea is that companies will come to the FDA with a list of production claims they are willing to abandon. The list might, but need not, involve all the production claims a company possesses. Of course, the companies won’t actually surrender claims until they see what the FDA has to offer in exchange.

Companies with numerous production claims may end up demanding a fair number of new approvals in exchange for voluntary withdrawals. This is going to be like the pit of old New York Stock Exchange. Do I hear a new therapeutic approval for our penicillin feed additive in swine in exchange for two growth-promoting claims in poultry? What about a preventive use claim for erythromycin in cattle?

Some changes in labels can occur at no cost to companies because they already hold approvals for the same drug at the same dose for both prevention and production purposes. But even in those cases, the companies can insist on an inducement to drop the claim.

If a company does not like what the FDA offers, it can simply refuse to go ahead with its “offer” to give up its production claims. The FDA may eventually decide to cancel the claim legally, but it’s a good bet that it will take the Agency years to act on that decision. Meanwhile the company continues to sell its drugs with no penalty.

These negotiations will take place behind closed doors over a three-year period to begin the day the final version of Guidance #213 is issued. Currently, the Agency is predicting final issuance by the end of March 2013. The companies will have three months from the day Guidance #213 is issued to submit their initial list of claims they are willing give up.

So far drug companies are being understandably cagey. None of them has publicly committed to give up any production claims. And it is unlikely that any will until they have firm commitments from the FDA for new approvals or other inducements.

If the FDA cannot persuade the companies to give up their claims, much time and resources will have been wasted, an outcome the FDA is anxious to avoid. This gives the drug companies strong leverage in the negotiations and means the agency will be willing to go far to induce their cooperation. That’s why designation of routine disease prevention in the acceptable pot is so important. Without it, the Agency would only have low volume claims to bargain with.

The public health payoff?

By the end of the three years, the agency and those drug companies participating in the Guidance #213 process will have presumably come to a set of agreements. If all goes according to the FDA’s plan, some—or perhaps all—of the production claims will have been withdrawn, many new approvals will have been granted, and all uses of antibiotics will be subject to veterinary oversight through prescriptions or VFDs.

The public health test of the policy is whether, when all the trading is over, the Agency has achieved a substantial reduction in overall quantities of antibiotic used in animal agriculture.

Considering the incentives on the part of companies to maintain sales and the FDA’s need to induce industry cooperation, it is hard to imagine that the end result of negotiations will be an overall reduction in antibiotic use. If so, that would be a colossal waste of public health resources.

But believe it or not, horse-trading for approvals may not be the end of what the FDA is willing to do to sweeten the pot for industry. We’ll talk about that in the next post.