Here on the East Coast, the arrival of hurricane season means something very different in 2013 than ever before. It reminds us: catastrophes like Hurricane Sandy are possible. It warns us: if you’re on the coast, you could face grave risk. And it asks: are you ready?

This post is part of a series on

This post is part of a series on

A Summer of Extremes: Confronting the Realities of Climate Change

Subscribe to the series RSS feed.

At the beach last summer, I sat musing (and later blogged) about the safety of nearby beachside homes. What would happen if a really big storm rolled through?

This summer, it’s all completely different. What was abstract was made plain to the nation by Hurricane Sandy, heartbreakingly. (And some of those houses on my local beach are gone, victims of a March Nor’easter.) Any sense of the durability of our seaside communities in the face of that kind of storm were wiped away. And our president, vowing “to shelter future generations against the ravages of climate change,” has recently announced federal funding to help vulnerable communities build resilience to our rapidly changing world. A year can make a stark world of difference.

So with the 2013 hurricane season upon us and anticipated to be “active” or “extremely active,” and with a century of significant sea level rise ahead of us, where do we stand?

A reminder: snapshots post-Hurricane Sandy

The states worst hit by Sandy are hard at the work of recovery. The storm broke entire communities – homes, businesses, and infrastructure now need to be rebuilt. If done right, these can be made safer, stronger, and better prepared for the next storm. Actual rebuilding is providing both encouraging and discouraging signs.

A home in Atlantic Highlands, N.J., damaged by Hurricane Sandy, is elevated in June 2013, to mitigate future flood risk. As we take resilience-building steps up and down the coast, some mundane and some that transform our cities and landscapes, we can expect to see the climate change society begin to emerge – one that recognizes this problem is not going back in the box. (Photo credit: Rosanna Arias/FEMA)

- In many places, new or expanded regulations and incentives are being used to help determine what should be repaired, what should be rebuilt differently, and what should be demolished and abandoned – in some cases, entire neighborhoods – in light of untenable, mounting risks.

- For struggling cities and towns, assistance can’t come quickly enough. New York and New Jersey have received nearly $15 billion, part of the over $50 billion Sandy Relief funds authorized by Congress. But the remaining scope of the job, from demolition to mold removal, is daunting.

- This spring, the federal government increased the rate at which it reimburses local governments in New York and New Jersey for recovery costs, from 75 to 90 percent. The ability to spread the costs across the entire nation is an essential tool we employ in disaster recovery. But it’s unclear whether, as currently designed, federal programs can bear the strain of mounting coastal disasters.

- And there are confusing twists. The new FEMA flood maps for New Jersey, for example, released in June, show large reductions in the areas of high flood risk, compared to preliminary maps released in December. These maps, which FEMA updates only infrequently, represent a critical opportunity to encourage smart choices about how and whether to build in vulnerable places. They do not, however, represent future sea- evel rise (nor, potentially, real current flood risk) and are thus an inadequate basis for long-lived decisions like where to build a home.

- At the same time, New Jersey seems poised to pass a waterfront development bill that would greenlight building in FEMA-designated Coastal High Hazard Areas (currently prohibited in all but Atlantic City), a move strongly criticized by some stakeholders, including state and national floodplain managers’ associations. “Permitting more high-risk development is not an appropriate response to New Jersey’s flood history (…), including Hurricane Sandy,’’ one letter said.

Beyond the scope of immediate disaster recovery and rebuilding, additional federal, state, and city programs are coming on line in these states with the potential to hardwire resilience-building into a range of decisions.

A warning: snapshots of East Coast risk

The risk of harm from coastal storms depends on our exposure, our vulnerability, and on the storms that actually strike us (see figure). Taken today, it’s not a pretty picture.

- Sandy had especially deadly aim, hitting the crowded Jersey Shore and a global mega-city. But the East Coast is simply teeming with people (more than 1000 people per square mile in some states), property, and infrastructure. It’s nearly impossible for a major storm to make landfall here and not affect us; our exposure to coastal storms is very high.

- But the degree to which we are harmed depends on how vulnerable we are. Recent data shows that the U.S. coastal population continues to grow, and could swell another 10 million between 2010 and 2020, to nearly 134 million people. If that population lived, for example, in storm-proof housing, with ample access to services and resilient infrastructure, vulnerability along our coast could be low. But, as neighborhoods like Breezy Point, NY, can attest, that’s not how we currently live.

- The hurricanes and Nor’easters we face along the East Coast may be growing stronger. But even if we had to contend only with the storms of our past, those would become more damaging by virtue of the additional water they have to “work” with. Sea level rise projections suggest we should expect the ocean to be one to two feet higher by mid-century – potentially higher still on the East Coast – amplifying the effects of storm surge.

We now know that some of the risks we live with along our coasts are too high. But we treasure being near the sea and are only beginning to grapple with what it would take to make our communities safe. As Joe Vietri, Army Corps of Engineers, lamented earlier this year at a UCS-convened experts meeting, “You still have communities rebuilding almost exactly where they were prior to the storm coming,” and “You still have people by the truckload moving into high hazard coastal areas.” For now, in other words, we live in great risk.

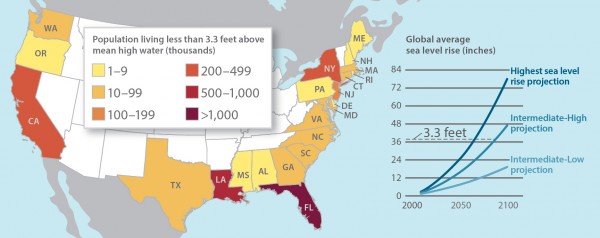

As this map shows, lots of Americans live in low-lying areas, and as the chart shows, low-lying areas are at risk of inundation later this century, to say nothing of increased storm surge in the intervening years. (Sources: NOAA 2012; Strauss et al. 2012)

A question: snapshots of preparedness and resilience — are we ready?

We are waking up to our situation. We know that waiting until after a major storm to build resilience is foolish. And we know that rebuilding as we always have in a storm’s wake is foolish. There have been good lessons drawn from Sandy and held up as the way forward nationally, many of these reflected in the president’s new Climate Action Plan. Our actions so far are just the very start.

In May 2013, workers construct a new sea wall, designed to better protect the Rockaways from future storm surge. Natural buffers, such as restored wetlands, can also help defend shorelines. (Photo credit: K.C.Wilsey/FEMA)

- In many American coastal communities, we’re finding ourselves forced onto the front line of climate change, out ahead of the country, and making major changes at great cost. In others, we’re taking the “ounce of prevention” approach and pro-actively directing resources toward beefing up our resilience. In others, we’ve been put on notice by storm impacts, by new FEMA flood maps, or by our insurance rates, that our risks are too high.

- The vast majority of communities, though, are waiting. (Just 13 percent of all U.S. cities have prepared climate adaptation plans, for instance, lagging behind the global average.) We’re waiting for guidance, support, capacity and funding. And some of us, presumably, are just preoccupied and will wait until a storm or other crisis forces our hand.

- But to linger here long is irresponsible. Communities need to do far more, far faster, with serious federal and state support in order to be storm ready in our sea level rise present, and resilient in our sea level rise future.

- And that federal support must include bold steps and follow through on climate change mitigation if we’re to manage this problem. We stand little chance of being storm-ready in a future of unrestrained climate change and rising seas.

In his recent speech, President Obama said of the global clean energy race “we can’t win it if we’re not in it.” And truly, we need to push hard to advance this race, for all our benefit. Preparing for unavoidable climate change is a different kind of race, but one we now must run to keep the things we care about safe. It’s about a hard struggle just to hold our ground, frankly, and we Americans need to come to terms with that. We need to see the 2013 storm season and every one that follows for what it is: something to come through as unscathed as possible as we race to build lasting resilience in a warming world.

Over the summer, in an ongoing blog series, a number of UCS colleagues and I will be exploring aspects of our vulnerability to sea level rise and coastal storms, and ways we can better protect ourselves. Please stay tuned.