Nuclear power plants are inherently dangerous. They generate tremendous amounts of energy, producing large quantities of highly radioactive material along the way. Strict controls are required to ensure that this potentially deadly combination is properly managed to an acceptably low risk level.

Even Robert Ripley, the creator of the well-known Rip1ey’s Believe It Or Not syndicated newspaper feature and museums, probably wouldn’t believe the response by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to potential natural gas hazards at two U.S. reactors.

In 1991, the NRC wrote a report taking the owners of the Fort St. Vrain nuclear plant in Colorado to task for not taking seriously the threat of a natural gas explosion near the plant. The report said that the plant owners did not adequately evaluate “external hazards that could have affected the safe operation” of the facility, and that a later safety evaluation “was too narrowly focused and did not consider additional possible malfunctions.”

Here’s what the NRC report said:

When the Fort St. Vrain facility was licensed in 1973, no natural gas pipelines were located nearby; thus, neither the licensee’s Final Safety Analysis Report nor the NRC staff’s Safety Evaluation Report addressed the hazards associated with natural gas present in geological formations in the area. In 1974, a 16-inch low pressure natural gas collection pipeline was constructed nearby by a natural gas company. This pipeline crossed a corner of the licensee’s property about 0.9 mile from the reactor building. At its closest point, this pipeline came within 0.85 mile of the reactor building. Although the pipeline was not constructed by the Public Service Company of Colorado (PSC), the Fort St. Vrain licensee, PSC was informed of its construction.

Between 1981 and 1983, 12 natural gas wells were installed within about one mile of the Fort St. Vrain reactor building. Seven of these wells were drilled on land owned by the Fort St. Vrain licensee by a company that had acquired the mineral rights from the licensee. Some of these wells were located within the Exclusion Area Boundary, but all were outside of the protected area. Nine of these wells were connected to the 16-inch collection pipeline by a 6-inch pipeline. The closest well was located 1,524 feet from the reactor building and the 6-inch pipe passed within 1,340 feet of the reactor building. Personnel involved in the drilling of these wells and the licensee’s manager of nuclear production concluded that possible accidents at the well sites would not produce adverse effects further than 300 feet from the wellheads. The licensee did not prepare any written analyses for any of the wells or pipelines.

Late in 1987, PSC allowed the drilling of a gas well within 1,183 feet of the Fort St. Vrain reactor building, which was within the Exclusion Area Boundary and 300 feet from the protected area fence. The pipeline associated with this well passed within 500 feet of the Fort St. Vrain switchyard. PSC prepared a 10 CFR 50.59 safety evaluation that concluded that in the event of a well fire caused by a blow out, the area affected both by the fire and the equipment needed to control it would not be larger than the existing drill site location. The licensee also concluded that the air temperature beyond a radius of 300 feet would not be elevated above the ambient temperature and therefore, the construction and operation of the closest well did not create the possibility of a new type of reactor plant accident or constitute an unreviewed safety question. The safety analysis did not evaluate the consequences of a rupture of either the 15-inch or 16-inch pipeline and did not postulate the release of a cloud of natural gas which might drift toward safety-related structures or equipment and ignite and either burn or detonate.

On August 18, 1989, the licensee shut down the Fort St. Vrain facility and. by letter of August 29, 1989, informed the NRC that the plant would be shut down permanently. In November 1990, the licensee submitted a proposed decommissioning plan. While reviewing the proposed decommissioning plan, the NRC became concerned that plans to introduce natural gas at Fort St. Vrain as part of a proposed repowering of the facility could lead to an accident that had not been reviewed. During this review, the NRC further determined that the licensee had not adequately addressed the natural gas already on site. The licensee responded by preparing analyses that addressed the limiting failures of all natural gas pipelines existing on site. Before completing these analyses, the licensee took prompt corrective actions to limit the amount of natural gas that could be released from a large rupture of the 6-inch collection pipeline. These actions consisted of closing a 6-inch valve and opening a 1 ½-inch bypass valve in the line that carried gas from the wells to the 16-inch collection pipeline. This configuration would reduce the gas leakage from a rupture in the 6-inch pipeline by reducing the flow of gas back from the 16-inch pipeline.

In August 1991, the licensee completed additional analyses which indicated that postulated explosions or deflagrations resulting from natural gas line ruptures with the 6-inch line open would not have resulted in unacceptable consequences at the Fort St. Vrain reactor building or at the switchyard. Nevertheless, PSC indicated that redundant check valves would be installed in the 6-inch pipeline to reduce the possibility that natural gas could flow back from the 16-inch pipeline, if the 6-inch line ruptured.

The natural gas pipelines and wells completed between 1973 and 1983 introduced additional unanalyzed external hazards that could have affected the safe operation of the Fort St. Vrain facility. These additional hazards were not evaluated by the licensee prior to their introduction to the site to determine the impacts on the safe operation of the plant and whether these hazards exceeded those evaluated during the initial licensing of the facility. For the gas well drilled in 1987, the licensee’s 10 CFR 50.59 evaluation was too narrowly focused and did not consider additional possible malfunctions before concluding that an unreviewed safety question was not involved.

Of course, by the time the NRC wrote this strong critique of how Public Service Company of Colorado responded to the hazard from the natural gas pipelines near its Fort St. Vrain nuclear plant, the issue was moot. The reactor had permanently shut down in August 1989. But you might hope this incident would help the NRC respond to other potential natural gas threats in a more timely way.

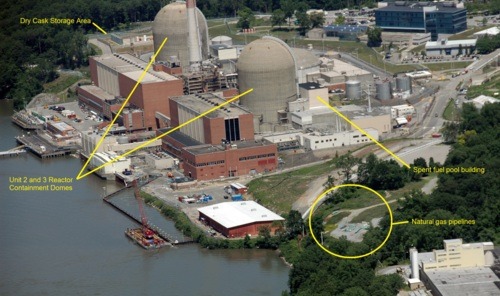

The figure below shows 26-inch and 30-inch diameter natural gas pipelines located about 400 feet from the Indian Point nuclear plant in Buchanan, New York. Unlike for Fort St. Vrain, the risk from these pipelines was discussed in the original safety analysis for Indian Point.

And while valves were installed in the pipelines near Fort St. Vrain to lessen the hazard, automatic shut-off valves have been removed from the pipelines near Indian Point.

Yes Mr. Ripley, the automatic shut-off valves relied upon to terminate the flow of natural gas from a ruptured pipe and lessen the threat to Indian Point’s safety equipment have reportedly been removed. The original safety studies for Indian Point credited the automatic shut-off valves with closing within four minutes to stop the release of natural gas. But the valves were removed from the pipelines by 1995 because they tended to close spuriously, thus interrupting the intended flow of gas.

Our Takeaway

If the NRC follows its Fort St. Vrain script, it will wait until after Indian Point permanently shuts down and then issue a scathing report criticizing the plant’s owner for improperly evaluating and controlling the natural gas hazard at the site. Until then, the people living near Indian Point will receive as much protection from the automatic shut-off valves that were removed from the pipelines for cost considerations as they do from the NRC pretending they are still installed.

The American public needs an effective regulator—not the NRC.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.