Reading the summary of the IPCC report on climate impacts, I was struck by the parallels between the major findings and the observed trends in the U.S.

The report summarizes eight key risks that people, policy makers, and communities will be facing as a result of the carbon pollution that is causing widespread, systematic changes to the climate. While the IPCC’s list wouldn’t exactly make Buzzfeed, Seth Borenstein simplified it so that it might and managed to report bad news with good humor.

What isn’t so funny is the prospect of more extremes in our future.

UCS has been highlighting the climate impacts affecting specific parts of the U.S. We’ve embarked on a series of climate impacts reports, informed by workshops, roundtables, and conferences around the country exploring how sea level rise, flooding, extreme heat, dry spells, and intensified storms are challenging communities across the nation.

Photo courtesy of AccuWeather.com

The combination of warming and drying trends predicted is particularly resonant. UCS has documented the increase in the incidence of heat waves in the Midwest along with its implications for human health, particularly in cities.

The IPCC also notes that North American adaptation needs are in the areas of forest management and municipal planning to reduce the impact of worsening wildfires and that greater resilience measures are needed for critical services. In the coming months we’ll be releasing reports outlining steps to electricity system resilience and the economic impacts of western wildfires.

Climate change in North America will be marked by warming and drying trends, extreme precipitation, hurricanes, and sea level rise.

Small island nations and poor countries are especially vulnerable to this aspect of climate change and sadly are more likely to have a greater risk of loss of life during these events.

Here in the U.S. too, events like Hurricane Sandy show that lower income communities suffer particularly harshly during and after the disaster. Those most exposed were hard hit and highlighted inequalities from historic shoreline protection projects and emergency response to restore infrastructure disruptions. This demonstrates the unique vulnerability that low-income communities will face even in a country like ours with greater resources to adapt.

Extreme weather has driven the federal flood insurance program into a debt of over $24 billion, a program that will be even more essential, given the IPCC predictions for sea level rise. In South Florida, cities are actively contemplating the disruption of livelihoods sea level rise will bring and have enacted a ‘four county compact’ that includes over 100 recommended steps to adapt to climate change and reduce the risks.

California’s recent drought caught the attention of the nation, as President Obama visited to announce his resilience fund proposal. It has also spurred rare bipartisan support for a drought relief bill sponsored by California Senator Diane Feinstein.

In a guest post, our California climate scientist, Juliet-Christian Smith points out that long-term changes in the way we manage water are going to be needed. Climate-resilient water management solutions needed include better groundwater management, urban water conservation, and more efficient agricultural water uses.

The IPCC report focuses a lot on risk management. “It’s much more about what are the smart things to do than what do we know with absolute certainty,” said Chris Field, a Stanford scientist who co-chaired the report committee.

In California, New York, and Florida, they have gone a long way to identify what some of those smart things are that they can do, and are at varying stages in implementing those measures. Fifteen states have completed adaptation plans and 59 percent of U.S. cities are pursuing adaptation planning. As of June 2012, 13 percent of U.S. cities have completed an assessment of their vulnerabilities and risks.

The top ranked impacts and issues identified by cities that conducted assessments were increased stormwater runoff (72%), changes in electricity demand (42%), loss of natural systems (39%), and coastal erosion (36%). Other issues that ranked closely behind were loss of economic revenue, drought, and solid waste management.

While the U.S. is far from being on track to reduce emissions as deeply as we needed, there are several new national measures in the wings and some proven state policies that will go a long ways to reducing domestic greenhouse gases emissions.

The EPA power plant carbon rules, due out for public comment June 1 of this year, will represent the first ever carbon limitations on electricity-generating power plants. If the EPA issues a strong rule it will be up to the states to create ambitious low-carbon energy plans.

California is already demonstrating the benefits of a low-carbon economy. As they continue implementation of AB32, a law aimed at reducing emissions, they are now beginning the process of setting a new emissions reduction goal for 2030.

Regional carbon trading regimes are also making progress on emissions reductions and beginning to set more ambitious goals as well. The Northeast Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative recently implemented a new 2014 RGGI cap of 91 million short tons, which will decline 2.5 percent each year from 2015 to 2020.

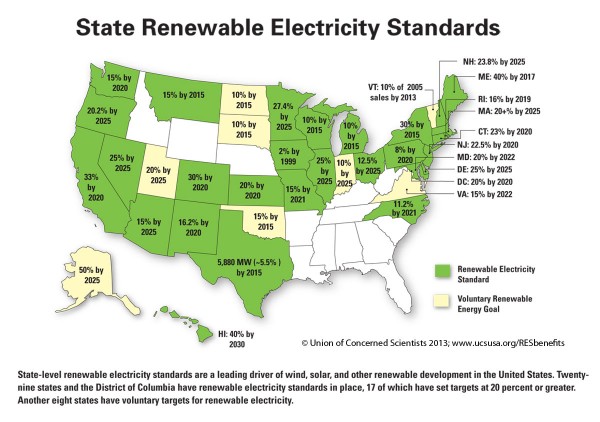

State policies like the RES have substantially contributed to the tremendous growth of renewable energy in this country since the 1990s and resulted in significant emissions reductions. Over the last year, efforts to repeal these laws have been attempted and repelled in dozens of states.

Just last week, Kansas rejected an attempt to repeal its RES for the second time largely because of the demonstrated economic benefits clean energy development has brought to the state. Now states like Michigan and Minnesota are in the process of strengthening their RES laws, potentially ramping up the percentage of their electricity from renewable sources to 30 to 40 percent.

State and regional climate and clean energy policies, combined with recent bipartisan efforts to address drought and disaster relief, provide some glimmers of hope that the U.S. can come together around common sense measures to reduce some of the risks of climate change.Those signals, combined with the dramatic rise in renewable energy production in the past year and the opportunity every state in the union will have over the next two years to draft a low-carbon energy plan makes me very hopeful that we will do some of those ‘smart things’ the IPCC report seeks to highlight.