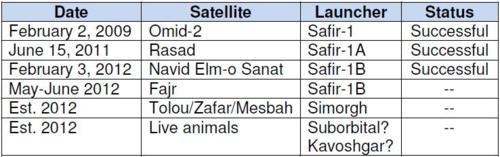

Iran has announced its plan to launch the Fajr (Dawn) satellite as early as next Wednesday, May 23. The Fajr, as you may recall, was meant to be launched in October 2011, and then by the end of the last Iranian year (which ended this past March 19). But the plan was postponed due to “some pilot tests,” according to Hamid Fazeli, the head of Iran Space Agency (ISA).

Fazeli also said that the Fajr satellite represents a “remarkable breakthrough” for Iran’s space technology, marking the transition of Iran’s satellite technology from research orbiters to practical and operational satellites.

This is an interesting comment and is presumably related to the ability of Fajr to maneuver on orbit—something new for Iranian satellites.To maneuver, the satellite will use a cold gas thruster—a simple but reliable system not unlike releasing air from a balloon.

This maneuver will boost the lifetime for the satellite. Iran’s previous satellites were able to stay in orbit only a few months before the atmosphere’s drag pulled them out of orbit, but Iran has said Fajr will orbit for a year and a half. Reports conflict about the initial and final orbits. Some say the satellite will move from an initial 250 km circular orbit to a final elliptical orbit with apogee at 400 or 450 km, while others say the final orbit will be a circular orbit at these higher altitudes. As we mentioned in an earlier post, such a maneuver should only take a few kg of fuel.

Based on lifetime, it appears the aim is a circular orbit at the higher altitude. According to Wang Ting, the lifetime of the Fajr in a 450 km circular orbit could be more than 460 days; in an elliptical orbit with its perigee at 250 km and apogee at 450 km the Fajr would come down after about 50 days, around the same lifetime as the Omid and Rasad (a few months), and longer than Navid (a few weeks).

Fajr is reportedly equipped with a domestically made GPS navigation system to help Iran keep track of its orbit. The satellite is intended to transmit pictures of the earth with a resolution of 500-1000 meters. (Recall that the resolution of Google Earth images for most of the earth is about 15 meters and for images of the United States is about 1 meter or better.)

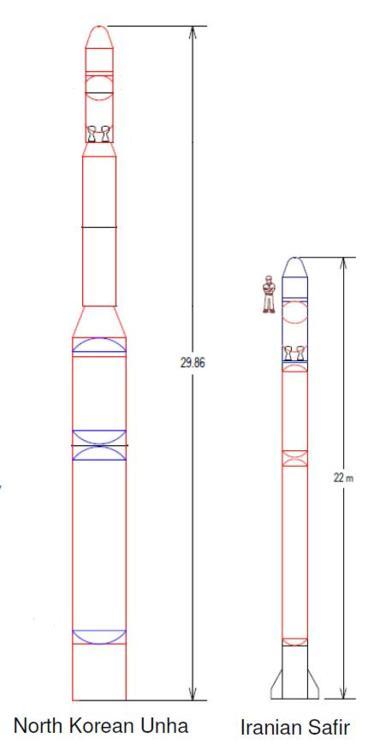

The Fajr satellite will be launched with a Safir 1B launcher, as was the Navid satellite this past February. The Safir launcher is essentially a Shahab-3 missile (which is very similar to the North Korean Nodong missile) as the first stage with a small second stage on top. It is much smaller than the Unha rocket North Korea recently unsuccessfully launched, with a mass of less than 30 tons compared to about 85 tons for Unha. It can only lift lightweight satellites to relatively low altitudes.

Figure adapted from this report.

Iran has a few more satellites in queue that can be launched this way, such as the recently announced Sharif and Nahid. (Different versions of this information appear, apparently from imperfect translation, so reader’s comments on the Persian language reporting would be appreciated.)

Iran also announced that it would send more living creatures into space in the next two or three months. Reports vary but point to the launch of the Tolou (Sunrise) and Zafar or Mesbah satellites by the end of the year. The Mesbah apparently refers to a home-grown version of the original Mesbah satellite; the original satellite was manufactured almost a decade ago for Iran by Italy, which failed to deliver the satellite to Russia for launch and which has not returned it to Iran either, presumably following the spirit of UN sanctions.

Because of their larger mass and higher planned orbits, the Tolou and Zafar satellites await the larger Simorgh launcher, which is being developed. The Simorgh appears to be closer in size and capability to the Unha, using in its first stage a cluster of 4 of the Safir first-stage engines. The original Mesbah satellite was 75 kg, so would need to go on the Simorgh as well if the new one is similar to the old one.

Farahi also said that Iran plans in its next Five-Year Development Plan to develop a satellite launcher that can launch a 1 ton satellite in a 1,000 km orbit. This would be well beyond the capability of the Unha or likely the Simorgh.

While discussion of this proposed launcher appears often in the press paired with the suggestion that a launcher capable of putting a satellite in GEO is imminent, getting to GEO requires considerably more capability.

More on Iranian launchers in a future blog post.