Coming into the Lima climate negotiations on December 1st, the US-China joint climate announcement, the European Union’s political agreement on its 2030 emissions reduction target, and the successful capitalization of the Green Climate Fund had all combined to create a sense of momentum and a positive mood.

But these developments had done little to resolve the sharp disagreements about which countries are responsible for taking which kinds of action on climate change, and these different perspectives on the issue of differentiation nearly derailed the final decision in Lima. As it was, the Lima decision on the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) was a disappointing, minimal outcome. If these conflicts over the issue of differentiation are not resolved, or at least significantly narrowed, they could threaten the prospects for agreement in Paris next December on a new, comprehensive post-2020 climate regime.

Some background…

In the 1992 Framework Convention on Climate Change, countries were split into two groups; the developed countries who collectively were responsible for the majority of historical greenhouse gas emissions were placed in Annex 1 of the treaty, and the developing countries were labeled as non-Annex 1. Under the Kyoto Protocol, only Annex 1 countries were required to take on binding emissions reduction commitments.

At COP 17 in Durban in 2011, countries agreed that the post-2020 actions to be negotiated by next year’s climate summit in Paris would be “applicable to all.” To the U.S., other developed countries, and some developing countries as well, this phrase meant that the strict “firewall” between Annex 1 and non-Annex 1 countries would not continue in the post-2020 agreement; different countries would take on different kinds of actions, but those would be based on their capabilities and their current national circumstances, not by the binary division of the world in the 1992 Framework Convention. However, other countries, in particular the Like-Minded Developing Countries group continue to insist that obligations in the post-2020 agreement must be based on the Annex 1 and non-Annex 1 groupings.

This post is part of a series on the UN Climate Change Conference in Lima (COP 20).

This post is part of a series on the UN Climate Change Conference in Lima (COP 20).

At the COP 19 climate summit last year in Warsaw, countries agreed that the obligations under the post-2020 agreement would be “nationally-determined,” with each country deciding for itself what kinds of actions it would take to reduce emissions. While there is general agreement that developed countries should continue to take on economy-wide emissions reduction commitments, there is no guidance in the Warsaw decision as to what kinds of obligations developing countries should take on, nor could there have been, given the deep divisions on this issue.

In the November 12th U.S. China Joint Announcement on Climate Change, China pledged to achieve an economy-wide peak in its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 or earlier. While this represents a significant advance in China’s national position over its previous intensity-based approach, it had no effect on its international stance in Lima on the post-2020 agreement, nor on the positioning of the Like-Minded Developing Countries group, of which China is a leading member. These countries continue to insist that developing countries should only take actions based on provision of finance and technology support from developed countries (which, of course, is not a condition of China’s pledged post-2020 emissions cap).

In Lima, these disputes about the responsibility of different countries arose not only in the discussions of post-2020 mitigation actions, but also in debates over finance, adaptation, and technology transfer.

In the final decision text put forward by COP President Manuel Pulgar-Vidal and adopted by consensus in the wee hours of Sunday morning, a new paragraph appeared: “Underscores its commitment to reaching an ambitious agreement in 2015 that reflects the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances.” This language was taken directly from the U.S.-China announcement, and was enough to paper over the clear differences on the differentiation issue and to allow unanimous adoption of the decision.

Differing approaches on differentiation

In their written submissions earlier this year, countries spelled out their approaches to several issues, including the issue of differentiation in the post-2020 agreement. While these positions reflect the well-known divisions between the developed countries and the Like-Minded Developing Country group, there are several proposals from other developing countries that provide a more nuanced view of the issue and represent a potential landing ground for the agreement next year in Paris.

In its submission, the European Union notes that one of the most challenging aspects of negotiating the post-2020 agreement in Paris will be how it reflects the Framework Convention’s principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR&RC). The EU believes that “to be consistent with this principle, Parties’ obligations must reflect evolving realities, circumstances, responsibilities and capabilities in a fair and dynamic way that is ambitious enough to keep us on track to achieve the below 2 degrees C objective.” The EU sees the process of countries submitting their Intended Nationally-Determined Contributions, or INDCs, together with the international process to consider and analyze them, as the way that CBDR&RC will be operationalized in the post-2020 agreement.

The U.S. also believes that differentiation will be determined by the INDCs put forward next year. The U.S. is quite clear that it cannot support a post-2020 agreement “based on a 1992-era bifurcated approach,” unless that approach “were on the basis of categories that are updated, in line with evolving realities.”

Norway calls for all countries to participate in the post-2020 regime, and sees a need to “differentiate according to the actual differences among Parties, and not on the basis of fixed categories of Parties.” Norway says that it “would expect all Parties with reasonable capacity and significant responsibility for global emissions” to put forward economy-wide emission reduction or emission limitation commitments.

Taking a directly counter approach, the Like-Minded Developing Countries group has called for the post-2015 agreement to be strictly differentiated between Annex 1 and non-Annex 1 countries, with the former taking on “economy-wide mitigation commitments” and the latter taking “mitigation actions subject to provision of support” from developed countries. China, which is a leading member of the LMDC, is quite firm in its belief that the goal of the negotiations on the new post-2020 agreement is “by no means to create a new international climate regime, nor to renegotiate, replace, restructure, rewrite, or reinterpret the Convention and its principles, provisions, and Annexes.”

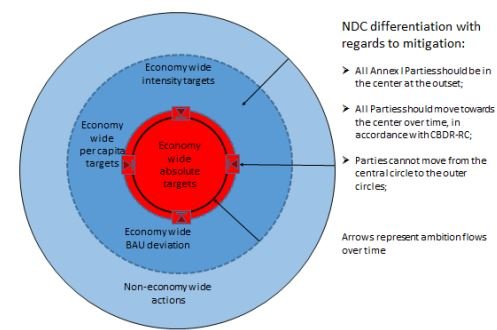

Brazil, on the other hand, has proposed an approach it calls “concentric differentiation,” that would see all countries putting forward “quantified mitigation targets and actions.” These could include economy-wide reduction targets relative to a previous base year, relative to a future projection of emissions, relative to unit of GDP (intensity target), or on a per capita basis, or actions that aren’t economy-wide. Developed countries would be expected to take the first approach, while least-developed countries would be encouraged to put forward non-economy wide actions. Other developing countries would be expected to put forward “economy-wide mitigation targets, leading to absolute targets over time, in accordance with their national circumstances, development levels, and capabilities.” Brazil’s proposal is summarized in this graphic:

Brazil sees this approach as fully consistent with the principles of the Convention, including differentiation between developed and developing countries. But to me, it represents a much more dynamic and effective approach to increasing ambition than the Annex 1/non-Annex 1 division of responsibilities that some countries state should be maintained ad infinitum.

In its submission, Mexico calls for developed countries to take the lead by putting forward economy-wide emission reduction targets, and for “other Parties in a position to do so” to follow their lead by doing the same. Similar to Brazil, Mexico envisions a spectrum of other possible commitments, including absolute limits on emissions, intensity targets, deviation from business-as-usual, and sectoral mitigation plans and strategies.

The Association of Independent Latin American and Caribbean countries (AILAC) states that while developed countries must take the lead, all countries should put forward contributions under the post-2020 agreement, based on their “national context, capabilities, responsibility and challenges,” and all countries should be “ambitious in contributing to global efforts to combat climate change.”

Finally, the Least-Developed Countries also call for developed countries and others in a position to do so to take on economy-wide emission reduction commitments, and for other countries to take on emission limitation commitments “in a form that is appropriate to meet their national circumstances.” They call on themselves to develop and implement low-carbon development strategies.

The way forward

The differentiation issue nearly blocked the final decision in Lima, where the stakes were actually quite small. In Paris next year, the stakes will be quite high: nothing less than the shape of the climate regime for the next several decades. It will not be possible to paper over sharp differences on this issue with artful language that different groupings can interpret in a way favorable to their position, as happened in the last hours of Lima.

Given the opposition of developed countries and of many developing countries to maintaining the Annex 1/non-Annex 1 groupings as the basis for obligations in the post-2020 agreement, it is clear that the position of the Like-Minded Developing Countries group is not viable. But the notion of purely self-determined obligations is not appealing to the vast majority of countries either; while it may represent the de facto basis for the first round of commitments under the Paris agreement, there will need to be more guidance in the agreement for subsequent mitigation commitments, as well as for the provision of finance, capacity-building, and technology transfer to developing countries, if it is to be acceptable to all. The submissions from Brazil, AILAC, Mexico, the Least-Developed Countries and others have much to offer in this regard.

Given that these submissions were made only recently, they have not received full discussion in the negotiating process. Creating the space for a full and focused discussion of the differentiation issue should be a priority for the new ADP co-chairs, Dan Reifsnyder of the United States and Ahmed Djoghlaf of Algeria. For as more than one delegate observed in Lima, differentiation is “the elephant in the room.” To make real progress towards agreement in Paris, there will need to be greater alignment around a shared vision of post-2020 differentiation. My hope is that through constructive discussion of the proposals put forward recently, together with the reality of differentiated INDCs being put forward by countries starting next March, we will start to see some breaking down of the polarization around the differentiation issue. Whether it will be enough to enable us to reach a comprehensive, ambitious post-2020 climate agreement in Paris remains to be seen — but it is an effort well worth making.