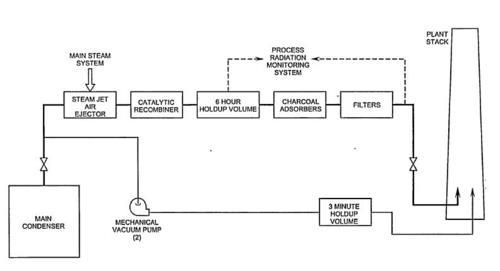

More than 25 years ago, workers were starting up the Perry nuclear plant in Ohio following its construction. Operators achieved the first criticality of its reactor core on June 6, 1986. Workers continued to perform various tests of systems to verify they were built per specifications and operated as expected. On June 18, workers tested the offgas system. During normal reactor operation, air and gases are removed from the main condenser and routed through charcoal beds to adsorb radioactive iodine and delay the release of radioactive krypton and xenon from the flow discharged from a tall stack. (See the figure for a schematic of the offgas system.)

The test required the initial temperature of the charcoal beds to be at least 150 degrees Fahrenheit. The charcoal beds contained several tons of charcoal and had several sensors to record their temperatures. Workers placed space heaters near the charcoal beds to warm them up to the limit. At 11 am on June 18, workers switched on the space heaters and monitored the slowly rising temperatures of the charcoal beds.

At 5:30 pm on June 19, workers turned off the space heater next to one of the charcoal beds after seeing smoke and smelling a pungent odor. Forty-five minutes later, the temperature at the bottom of another charcoal bed jumped 10 degrees in an hour – a dramatic increase following a day of very gradually rising temperatures. Workers turned off the space heaters for the rest of the charcoal beds but turned back on the space heater for the first bed.

At 8:41pm on June 19, the temperature in the middle section of a charcoal bed soared from 112 degrees to greater than 250 degrees. By 9:10 pm, workers had turned off all space heaters. By 9:20 pm, the temperature in middle section of another charcoal bed had risen from 126 degrees to greater than 250 degrees. Suspecting that both temperature indications were bad, the operators dispatched a technician to investigate.

The technician reported the temperature sensors had failed, which he assumed because they were reading greater than 1,000 degrees. Workers observed smoke in the area around 10:45 pm and concluded that insulation on the cables of the “failed” temperature sensors was smoldering.

By 12:30 am on June 20, the temperature at the top portion of a charcoal bed climbed from 220 degrees to greater than 250 degrees. Workers pulled out drawings while exploring a theory that a common-mode failure had caused all the temperature sensors to fail high.

At 10 am on June 20, workers entered the offgas system area and measured the surface temperature of charcoal bed container to be 254 degrees. Air flow through the charcoal beds was terminated. At 11:45 am, the operators declared an Unusual Event – the least severe of the NRC’s four emergency classification levels – based on fire in one or more charcoal beds. At 12:19 pm, operators began purging the charcoal beds with nitrogen gas to extinguish the fires.

During the next few days, operators kept nitrogen flowing through the charcoal beds. The Unusual Event was cancelled at 11:25 am June 23, when the temperatures on all charcoal beds suggested that the fires were out.

At 6 pm on July 6, operators resumed air flow through the charcoal beds. By 7:10 pm, the temperature readings for two charcoal beds had soared to greater than 250 degrees. At 8:37 pm, operators declared another Unusual Event for fires in the charcoal beds. Nitrogen flow through the beds was resumed at 11:07 pm. At 4:45 pm on July 8, the second Unusual Event was cancelled after temperatures showed the fires to be out again.

An investigation determined that the space heaters used to warm up the vaults caused the fire. The manuals for the space heaters warned against using them within five feet of combustible materials. The space heaters were placed within two feet of the charcoal beds. Analysis showed that the space heaters produced charcoal bed surface temperatures of nearly 1,000 degrees.

There was confusion in Perryville about charcoal’s physical properties. On June 23, they told the NRC that the minimum ignition temperature of the charcoal was about 1,000 degrees. They later discovered that the supplier of the charcoal certified the minimum ignition temperature as 482 degrees. But that certification temperature was based on different flow rates through the charcoal than had been used at Perry. During tests conducted after the fire under laboratory conditions matching the plant configuration, the actual measured ignition temperature was as low as 307.4 degrees.

Our Takeaway

First, it’s disappointing how many times instruments installed with the sole purpose of flagging problems are ignored. Fission Stories #80 involved two sets of instrument warnings that were dismissed just last year by workers. In this Perry case, workers not only ignored the warnings from the instruments, they blamed the instruments’ failure for causing the smoke they smelled.

Second, it’s disappointing how much money is spent after miscues like this one. Wiser investments entail lab testing conducted beforehand so as to perform actual tests at the multi-billion nuclear plant using solid information instead of flimsy hunches, guesses, and suppositions.

If knowledge is power, tasks at nuclear plants are performed too frequently in a power vacuum.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.