Pregnancy Advice: Caffeine’s ok. Some caffeine is ok. No caffeine.

Breastfeeding Advice: Start solids at 4 months. Start solids at 6 months. Exclusively breastfeed for one year.

First Foods Advice: Homemade baby food. Store-bought baby food. Spoon feeding. Baby-led weaning.

My experience of being pregnant and having a baby in modern times has meant getting conflicting advice from the different sources I consulted, specifically surrounding nutrition. Depending on the google search or midwife I spoke to, I heard different daily amounts of caffeine suitable while pregnant. Depending on the lactation consultant that popped into my hospital room, I heard different levels of concern about the amount I was feeding my newborn. And now that I’m about to start solid foods with my six-month old, I have heard conflicting information about when, how, and what to start feeding my child. How is it so difficult to find what the body of evidence says about these simple questions that parents have had since the dawn of time? When I discovered that past editions of the Dietary Guidelines didn’t address the critical population of pregnant women and infants from birth to two years, I wondered how it was possible that there was this huge gap in knowledge and guidance for such an important developmental stage. That’s why I’m very excited that the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) will be examining scientific questions specific to this population that will inform the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines and have recently begun that process.

In the meantime, I will be starting my daughter on solids this week and have been trying to find science-supported best practices. It has been shockingly hard to navigate and I became reminded of the interesting world of the baby food industry that I became acquainted with as I researched and wrote about added sugar guidelines specifically for the 2016 UCS report, Hooked for Life.

The history of baby food and nutrition guidelines

Amy Bentley’s Inventing Baby Food, explains that the baby and children’s food market as we know it today is a fairly new construction, stemming from the gradual industrialization of the food system throughout the last century. Early on in the history of baby food marketing, a strong emphasis was placed on convincing parents and the medical community of the healthfulness of baby food through far-reaching ad campaigns and industry-funded research. The Gerber family began making canned, pureed fruits and vegetables for babies in 1926 and in 1940 began to focus entirely on baby foods. During this time, it was considered a new practice to introduce solid foods to babies before one year. In order to convince moms of the wholesomeness of its products, Gerber commissioned research touting the health benefits of canned baby foods in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association (ADA) and the company launched advertising campaigns in the Journal and women’s magazines. Quickly, Gerber’s popularity and aggressive marketing campaign correlated with the decrease in age of earlier introduction of solid foods as a supplement to breast milk. Earlier introduction of foods meant an expansion of baby food market share, which meant big sales for Gerber.

All the while, there were no federal guidelines issued for infants. Gerber took advantage of this gap in 1990 when they released their own booklet, Dietary Guidelines for Infants, which glossed over the impacts of sugar consumption, for example, by telling readers that, “Sugar is OK, but in moderation…A Food & Drug Administration study found that sugar has not been shown to cause hyperactivity, diabetes, obesity or heart disease. But tooth disease can be a problem.” The FDA study that Gerber refers to was heavily influenced by industry sponsorship, and the chair of the study later went on to work at the Corn Refiner’s Association, a trade group representing the interests of high-fructose corn syrup manufacturers. In fact, evidence has since linked excessive added sugar consumption with incidence of chronic disease including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity.

Today, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), World Health Organization, and the American Academy of Family Physicians all recommend exclusive breastfeeding until six months using infant formulas to supplement if necessary. AAP suggests that complementary foods are introduced around 4 to 6 months with continued breastfeeding until one year. But what foods, how much, and when is a little harder to parse out. Children’s food preferences are predicted by early intake patterns but can change with learning and exposure, and flavors from maternal diet influence a baby’s senses and early life experiences. There’s research that shows that early exposure to a range of foods and textures is associated with their acceptance later on. And of course, not all babies and families are alike and that’s okay! There are differences related to cultural norms in the timing of introduction of food and the types of food eaten. Infants are very adaptable and can handle different ways of feeding.

There’s a lot of science out there to wade through, but it is not available in an easy-to-understand format from an independent and reliable government source. That’s what the 2020 Dietary Guidelines have to offer.

2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines: What to expect

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans is the gold standard for nutrition advice in the United States and is statutorily required to be released every five years by the Department of Human Health Services (HHS) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). These guidelines provide us with recommendations for achieving a healthy eating pattern based on the “preponderance of the scientific and medical knowledge which is current at the time the report is prepared.” Historically, the recommendations have been meant for adults and children two years and older and have not focused on infants through age one and pregnant women as a subset of the population.

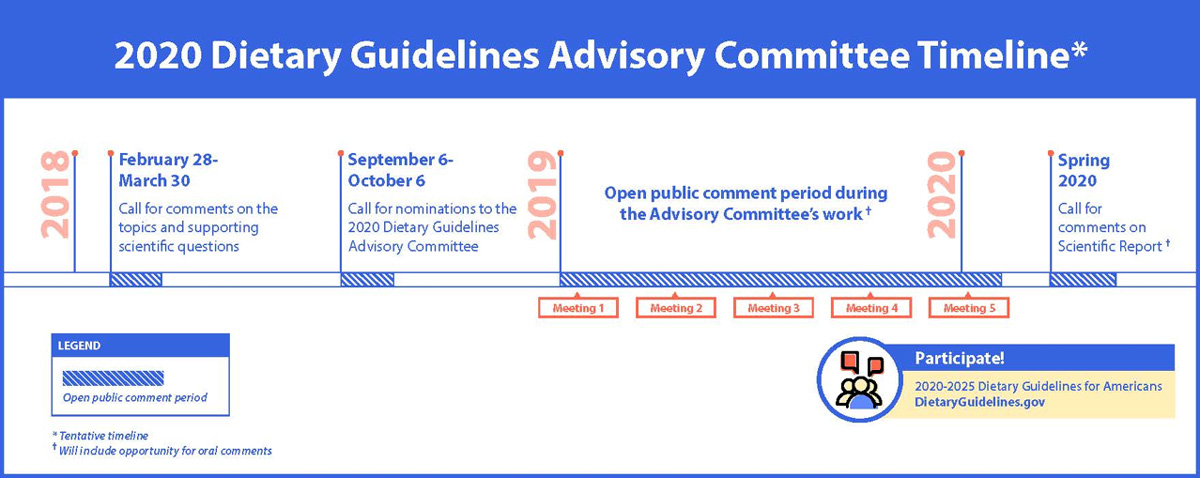

The freshly chartered DGAC will be charged with examining scientific questions relating to the diets of the general child and adult population, but also about nutrition for pregnant women and infants that will be hugely beneficial to all moms, dads, and caregivers out there looking for answers.

While I was pregnant, my daughter was in the lower percentile for weight and I was told by one doctor to increase my protein intake and another that that wouldn’t matter. I would have loved to know with some degree of certainty whether there was any relationship between what I was or wasn’t eating and her growth. One of the questions to be considered by DGAC is the relationship between dietary patterns during pregnancy and gestational weight gain. I also wonder about the relationship between my diet while breastfeeding and whether there’s anything I should absolutely be eating to give my daughter all the nutrients she needs to meet her developmental milestones. DGAC will be looking at that question (for both breastmilk and formula) as well as whether and how diet during pregnancy and while nursing impact the child’s risk of food allergies. The committee will also be evaluating the evidence on complementary feeding and whether the timing, types of, or amounts of food have an impact on the child’s growth, development, or allergy risk.

At the first DGAC meeting on March 29-3o, the USDA, HHS, and DGAC acknowledged that there are still limits in evaluating the science on these populations due to a smaller body of research. Unbelievably, there’s still so much we don’t know about breast milk and lactation, and in addition to government and academic scholarship, there are really interesting mom-led research projects emerging to fill that gap.

The Dietary Guidelines are not just useful for personal meal planning and diet decisions but they also feed directly into the types of food made available as a part of the USDA programs that feed pregnant women and infants, like Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC); and the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP). Having guidelines for infants on sugar intake in line with the American Heart Association’s recommendation of no added sugar for children under two years old, would mean some changes to the types of foods offered as a part of these programs.

Nutrition guidelines will be a tool in the parent toolbelt

But if there’s one thing I’ve learned as I’ve researched and written about this issue and now lived it, is that while the scientific evidence is critical, there are a whole lot of other factors that inform decisions about how we care for our children. Guidelines are after all just that. As long as babies are fed and loved, they’ll be okay. What the guidelines are here to help us figure out is how we might be able to make decisions about their nutrition that will set them up to be as healthy as possible. And what parent wouldn’t want the tools to do that?

As I wait anxiously for the report of the DGAC to come out next year, I will do what all parents and caregivers have done before me which is do the best I can. I have amazing resources at my disposal in my pediatrician, all the moms and parents I know, and local breastfeeding organizations. Whether my daughter’s first food ends up being rice cereal, pureed banana, or chunks of avocado, it is guaranteed to be messy, emotional, and the most fun ever, just like everything else that comes with parenthood.