As electric vehicle (EV) aficionados like to say, the cleaner the grid, the cleaner the EV.

That certainly rings true. Unlike gasoline-fueled vehicles, all-electric vehicles don’t emit tailpipe pollution of any kind, smog-forming or climate change-creating. But given that EVs are charged by electricity, they are indirectly responsible for the pollution from the source of that electricity, as well as the emissions from producing whatever fuels those power plants burn. Regardless, when compared to a gasoline car, whose fuel efficiency and emissions will remain the same for the life of the car, an EV will be accountable for less and less pollution over time as utilities transition from fossil fuels to wind, solar and other renewable sources.

A new analysis by UCS Senior Engineer David Reichmuth bears that out. From 2018 to 2019, despite an administration that promised to prop up the coal industry, EVs did indeed get cleaner. And the numbers are all the more impressive when you consider the improvements over the last decade.

EV sales in the United States over the past year, in the midst of a pandemic, also were encouraging. From the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of this year, EV sales jumped nearly 45 percent, and sales from this January through March reached nearly 100,000, a record for one quarter. So far, this year’s sales are outpacing 2020’s total EV sales of 252,548. That said, EV sales were less than 2 percent of all US vehicle sales last year.

Given that the transportation sector is now the top US carbon polluter, responsible for 29 percent of all US carbon emissions, it is imperative to transition from gasoline to electricity as quickly as possible. Now, with a new administration promoting EVs and major automakers rolling out more EV models, are EVs poised take off?

I recently caught up with Reichmuth to find out more about his new analysis and ask his opinion on the short-term and long-term prospects for EVs. Below is an abridged version of our conversation.

EN: Let’s start with your top findings, which—as I already mentioned—show that EVs are getting cleaner.

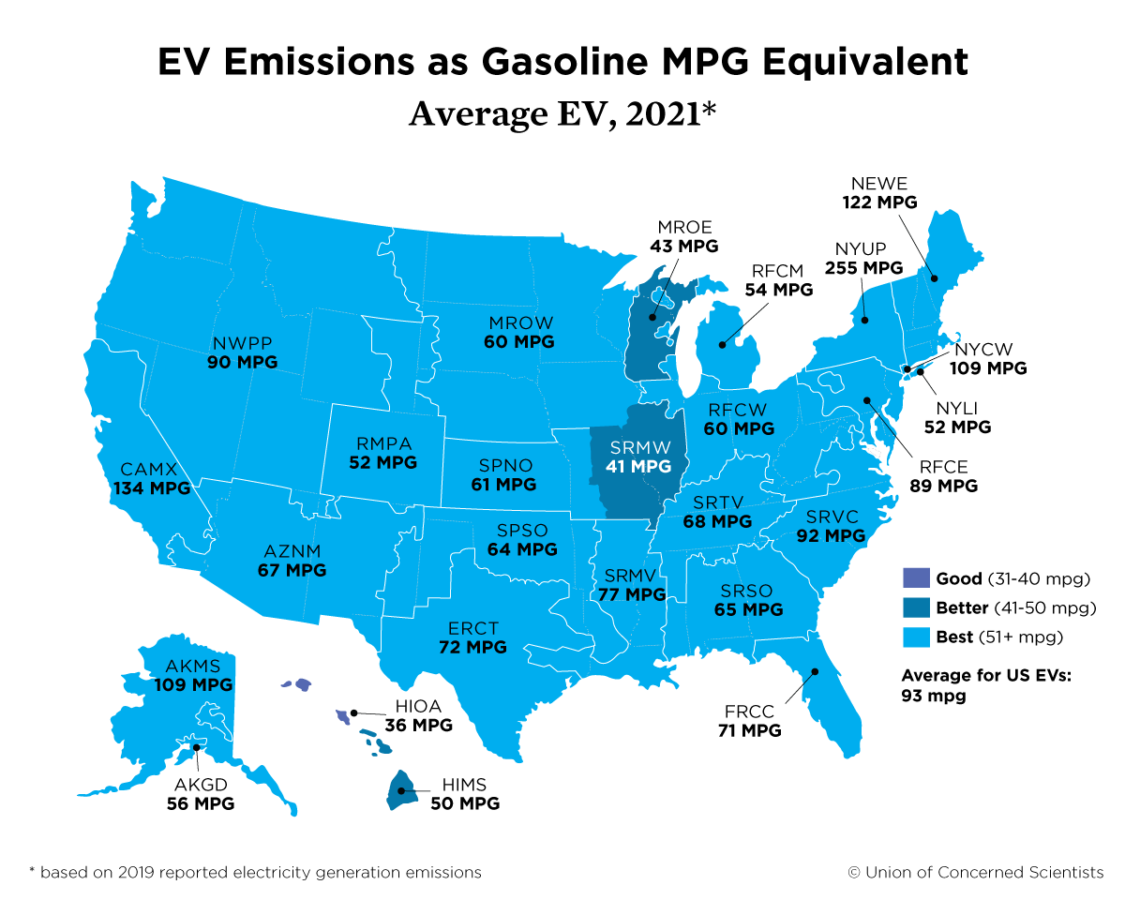

DR: Yes, that’s right. Driving the average EV is accountable for significantly less carbon pollution than driving a gasoline car, and that difference has become more pronounced as time goes on. Given where EVs have sold to date, their emissions—based on 2019 power plant emissions data—are equivalent to a gasoline car that gets 93 miles per gallon (mpg), which is dramatically better than even the most efficient gasoline hybrid. Last year, when we conducted the same analysis based on 2018 power plant data, EV emissions were equivalent to an 88-mpg gasoline car, so the “climate pollution gap” between gasoline and electric vehicles is continuing to widen.

EN: UCS did its first analysis comparing carbon emissions from EVs and gasoline-powered vehicles back in 2012 based on 2009 power plant data. Now that you’ve looked at carbon emissions based on 2019 data, how have things improved?

DR: There’s a major difference between our first analysis about a decade ago and today. The electricity sector has experienced a massive shift. Coal-fired plants, which generated 45 percent of US electricity in 2009, produced only 23 percent in 2019. Over that same time, grid operators added more solar and wind power. All of these changes mean driving an EV in 2021 is much cleaner than 10 years ago.

EN: Where are the “cleanest” areas of the country to drive an EV?

DR: Upstate New York is the cleanest place to drive an EV. The emissions attributable to an average EV there is the equivalent of driving a 255-mpg gasoline car. California and New England are also among the top clean areas, where driving an EV is comparable to driving a 134-mpg and 122-mpg gasoline car, respectively. Why are these regions so clean? A major reason is their grids get very little electricity from coal.

But there are substantial benefits even in states where the grid hasn’t switched over to cleaner power yet. An average EV in Ohio, for example, is accountable for the same amount of carbon pollution as a 60-mpg gasoline car, about half of the emissions of the average new gasoline car that gets only 31 mpg.

EN: As you point out in your analysis, pickup trucks and other, larger vehicles, no matter how they are powered, are less efficient. Are EV pickup trucks still a good idea?

DR: First off, a more efficient EV will have lower emissions than a less efficient one, so I would encourage people to choose the most efficient vehicle that meets their needs. But, for people who need a larger vehicle, such as a pickup truck, driving an electric version would be considerably less harmful to the climate than driving a gasoline or diesel truck.

For example, the gasoline version of the Ford F-150 pickup truck gets around 20 mpg. While the official efficiency data are not yet available, I estimate that the emissions associated with the recently announced Ford F-150 Lightning all-electric pickup, when driven in California, would be equal to driving an 85-mpg gasoline vehicle. In other words, driving the electric pickup would have less than a quarter of the carbon emissions of a gasoline version of the same vehicle.

EN: To make it easier for consumers to choose EVs, there will need to be a significant investment in charging infrastructure. President Biden has called for installing 500,000 charging stations nationwide by 2030 in his American Jobs Plan. What investments do you think will be needed to support charger deployment?

DR: It is very promising that President Biden’s plan includes such a large investment for electric vehicles, including EV charging infrastructure. Half a million chargers represents a significant down payment on the infrastructure we will need to transition from gasoline to electricity.

As the US EV fleet continues to grow, we will of course need charging stations along highways to support longer trips. But we also must make sure deployment is equitable and chargers are installed in all communities, including low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. City residents who do not have access to off-street parking with electricity—people who live in apartments, condominiums and multifamily housing—will have to be able to charge their vehicles as well.

EN: What else should the federal government do to promote EVs?

DR: Besides investing in EV charging infrastructure, there are a number of other things the government could do to accelerate the transition from petroleum-fueled transportation.

First, the federal government should set stronger vehicle emissions standards to ensure there will be more EVs on the road and—at the same time—make sure that any gasoline cars sold are as efficient as possible. To avoid the worst impacts of climate change, we’ll have to switch to electric vehicles. But keep in mind, automakers will still be selling gasoline vehicles over the next decade, so it will be critical to require those vehicles to meet tougher, achievable emissions standards.

Second, the government should strengthen existing EV purchase incentives programs. For example, Congress should update the federal tax credit, which is as much as $7,500 for electric passenger cars and light trucks, and consider allowing consumers to receive the incentive when they purchase the vehicle instead of when they file their taxes the following year. Likewise, expanding purchase incentives to include used EVs would help make EVs a viable option for car buyers shopping in the used car market.

The federal government needs to do more to help US auto manufacturers make the transition to electric vehicles, too. Incentives will be important, but the government also should reward automakers that have strong labor standards, use domestic materials in their EVs, and assemble EVs here at home. Expanding existing federal loan and grant programs and funding new ones that promote domestic EV manufacturing would help make US automakers more competitive as the United States—and the rest of the world—electrify their cars and trucks.

The Biden administration’s American Jobs Plan calls for investments in many of these EV incentive programs, and we look forward to seeing it move forward in Congress.