Climate science is having its moment. With the recent administration changes, climate change is getting attention at the national level through much-needed bold and ambitious federal policy developments. “We must listen to science — and act,” the Biden administration wrote in an Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, signed by President Biden within a month of his inauguration. More recently, the $2 trillion infrastructure plan proposes billions of dollars dedicated towards building climate resilience and environmental justice in impacted communities.

Before I go any further, I want to pause and reflect what equity means to me. As a first-generation immigrant, I have spent several hours of my life thinking about this term. I thought equity meant equal opportunities for me and my White, Non-White, Black, and Hispanic peers at my university and workplace. Throughout my Ph.D., I continuously thought about how my research would influence these equity challenges in the society. I thought about how climate change disproportionately impacts the vulnerable island nations, which became the focus of my dissertation.

Closer to home, I started thinking about how these impacts are prevailing and even enhancing inequities for several underrepresented groups. You see, while we all encounter the same hurricane, the way we deal with it, also known as our adaptive capacity, differs based on our ethnicity, socio-economic status, etc. These factors continue to affect post-disaster recovery influencing the financial aid and support and unequal opportunities to bounce back for people of color. Once I completed my degree and developed my voice as a climate scientist, the notion of equity developed more fully for me. Equity now does not mean equal opportunities, rather, it means targeted opportunities. Once I understood that the concept of equity is about the communities and what those communities need, it became imperative to facilitate these opportunities for the ones who are at the forefront of these climate impacts through my work.

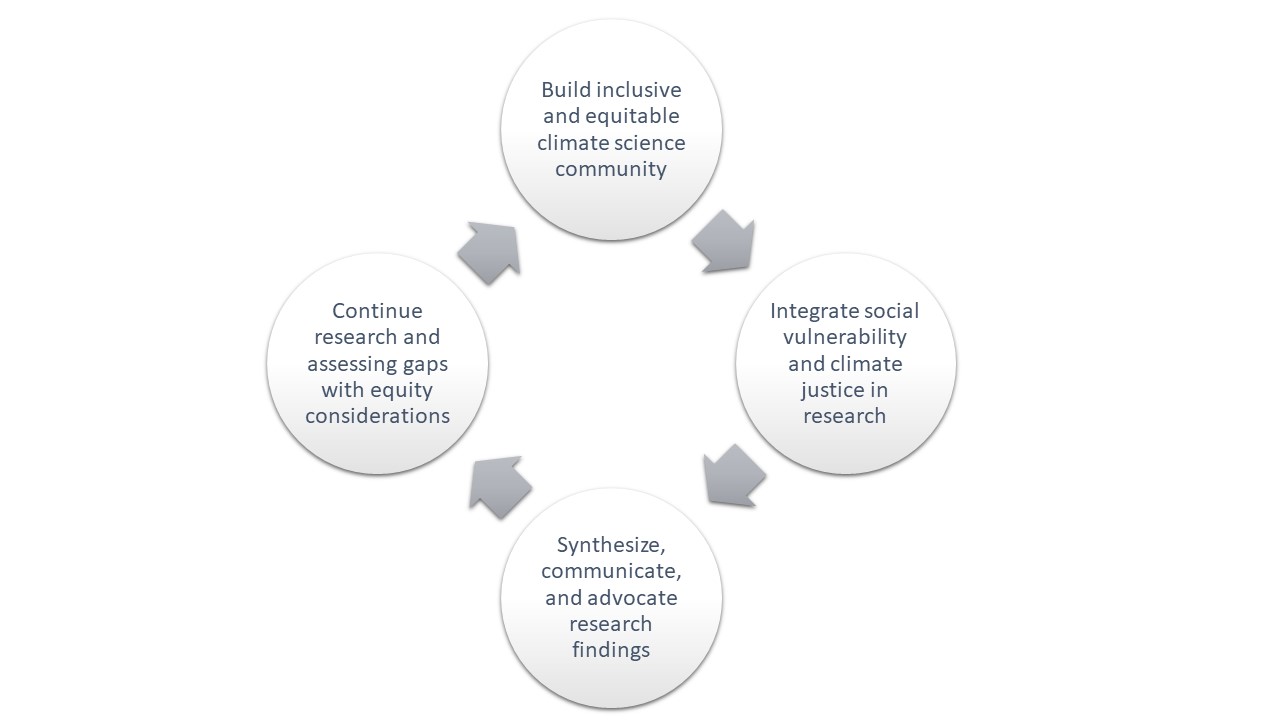

Earlier, I mentioned the attention at the federal policy level to tackle the climate crisis. This comes with a massive responsibility. Now is the time for climate scientists to build on this momentum and go the extra mile to ensure that these policies are shaped in an equitable manner. In fact, as we enjoy this spotlight, there are opportunities for all types of climate scientists – physical, social, natural and interdisciplinary – to employ an equity lens in their work. For me and many others in the scientific community, embedding an equity framework in our work is not only possible but unavoidable. Pulling from my research and practical experiences, I present a four-step framework that researchers and scientists can incorporate to fully harness the potential of this current climate policy landscape and facilitate equitable solutions for their geographies of interest.

Step 1: Start with building an inclusive and equitable climate science community

There is strong evidence indicating the lack of diversity within environmental disciplines in general and climate science specifically. As a female climate scientist of color, I have witnessed this first-hand in my classes, academic conferences, and seminars. For climate scientists, academics and researchers, it requires continuous investments to create more equitable institutions and mechanisms that enable more inclusive environments. It was not too long ago when we started having the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice workshops at my university. While having these active conversations is the first step, the frontline communities should be actively included outside classrooms by targeting outreach to minority groups during admissions and bringing attention to the work from minority and marginalized researchers in our classrooms.

Step 2: Utilize integrated research approaches by actively weaving themes of social vulnerability and climate justice in your work

For climate scientists, striving for equity goes beyond our discipline. It requires weaving theoretical understanding of climate justice and social vulnerabilities in our research. For instance, many social scientists are now using bottom-up approaches and co-producing research with marginalized communities to understand climate impacts. However, this should not limited to social scientists. Natural and physical scientists should build and place their findings in the context of a region’s social vulnerability using publicly available datasets such as FEMA’s National Risk Index, CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index, etc.

Step 3: Synthesize, communicate, and advocate research findings from local to national government institutions

There are several ways for scientists to translate their findings into policy recommendations. Creating easy-to-understand and digestible summary documents and letters is one of my favorite ways to garner the attention of local leaders in the county that I live. The good news for climate scientists is that there is also considerable space to support advocacy efforts and messaging. In fact, research suggests that advocacy poses no implications to the scientific credibility of climate scientists. While doing so, fine-tuning the messaging to make it relevant and accessible for frontline communities as well as their decision-makers is crucial to this step.

Step 4: Continue conducting research and identifying gaps with equity considerations

Like all scientists, climate scientists are driven by a curiosity for the world around us. As we continue to conduct research in our subfields and identify further research gaps, it is necessary to do so with equity considerations. For young and upcoming researchers, there are opportunities for new interdisciplinary projects by forming their committees with faculty from diverse fields of expertise. Existing researchers downscaling climate models and analyzing impacts should consider how the changing climate affects vulnerable communities, and work with these communities and their local knowledge to understand these impacts. Research focusing on mitigation and adaptation should, when possible, include an assessment and production of these options with historically marginalized communities. And when identifying potential policy solutions, scientists should consider whether they lead to equitable outcomes and are supported by the communities who are most impacted—who, from the start, should be an integral part of the project planning process.

Reflecting on my Ph.D., I understand that research questions are often limited in their scope, making it difficult to establish a universal set of guidelines. These steps are not meant to be one-size-fits-all. What’s more, policy creation and implementation processes are not linear and are rather messy in a real-world application. However, as new climate policies are being shaped, it is our responsibility to ensure that these policies create a resilient future for all of us. I welcome this role wholeheartedly. I hope this framework helps you get started, too.