Oregon and Washington are bracing for record-breaking heat this weekend. While extreme heat presents dangers no matter where it occurs, early season heat waves (like this one) occurring in places historically unaccustomed to heat (like the Pacific Northwest) are particularly dangerous for human health. The Oregon legislature has just a few days left in its 2021 session. With two climate-focused bills on the docket this week, will legislators act to protect their constituents from the kind of heat they’re experiencing right now?

Record-breaking heat in Oregon and Washington

We’re not even a week into the official summer season this year, yet we’ve already seen record-breaking temperatures from New England (95°F in Millinocket, ME, on June 7) to the Southwest (111°F in Kingman, AZ, on June 15), and from the Plains (105°F in Omaha, NE, on June 17) to the Central Valley (110°F in Sacramento, CA, on June 18). Like the Eye of Sauron, it has seemed as if extreme heat has cast its scorching gaze on one region after another.

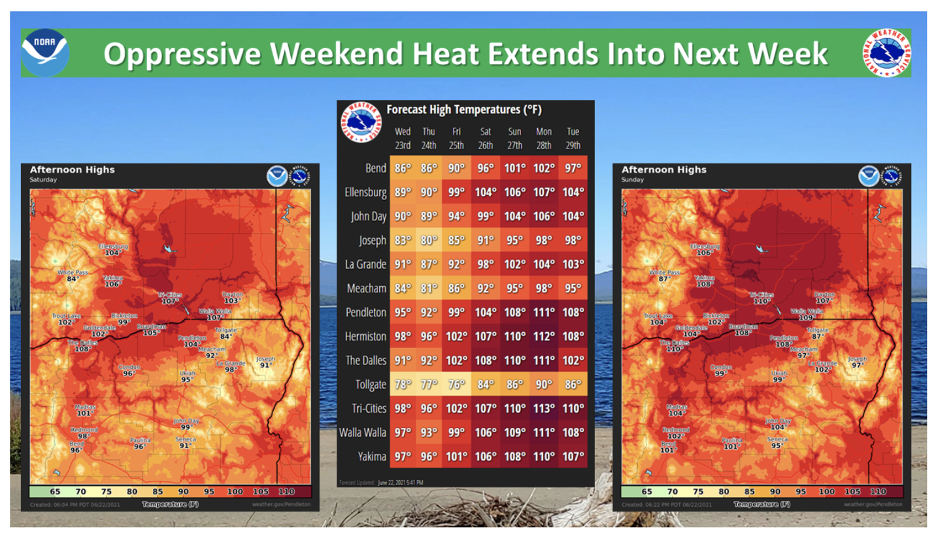

As we close out this week and look ahead to the first weekend of the summer, it’s clear that the Eye of Sauron has turned to the Pacific Northwest. In anticipation of this heat, the National Weather Service has issued excessive heat warnings and watches for most counties in Oregon and Washington. In Oregon, meteorologists are forecasting temperatures as high as 113°F for parts of the state where, high temperatures are in the low 80s at this time of year. While coastal areas will likely fare better, even cities famous for being delightfully cool in the summer, like Seattle, could see temperatures nearly 30°F above average.

This is not a part of the country that regularly experiences heat like this.

Historical records show that most years over the last half century, Portland, OR, for example, does not experience any days when the daily maximum temperature exceeds 100°F. Since 1975, there have been fewer than 25 days with temperatures above 100°F in Portland—that averages out to less than one day per year.

I can personally vouch for the normally cool nature of Oregon summers: Here’s me on a family camping trip in Oregon in 1989.

We’d come from our home in balmy Pittsburgh, PA, each bearing a single pair of pants and a thin sweatshirt for what turned out to be two weeks of camping in damp, chilly conditions. Those warm sweatshirts my sister and I are wearing were purchased at Crater Lake National Park after about ten days of endless shivering.

Those are just two data points—one of them more of an anecdote than a data point, of course—but suffice it to say that the heat wave unfolding in the region is likely to break records in many places.

What makes Pacific Northwest residents particularly vulnerable to heat?

Heat waves tend to be more harmful to human health in regions where heat is less common, including the West. Hospitalizations for conditions exacerbated by heat start rising in the Western region when the heat index (a combination of temperature and humidity often called the “feels like” temperature) rises above 80°F. In contrast, across the South, those hospitalizations don’t start rising until the heat index reaches 100°F. Reasons for this include that people in less heat-prone places are less physically acclimated to such conditions and that homes and buildings are less likely to have adequate cooling. Data from the American Housing Survey suggests that only about one-third of homes in Seattle and two-thirds of homes in Portland have air conditioning compared to nearly all homes in Tampa, Kansas City, or Las Vegas.

While all Pacific Northwest residents should heed local heat warnings, those who lack air conditioning or another form of cooling—or those who lack the ability to pay for cooling—could be at risk of experiencing heat-related symptoms during this heat wave. However, there are some groups are likely to be more exposed to heat than others:

- People without homes

Washington and Oregon have relatively large homeless populations. Particularly when homeless people are unsheltered, heat exposure presents major health risks. In Maricopa County, Arizona, which is home to the city of Phoenix, 146 homeless people died of heat-related causes last year alone, accounting for more than half of all heat-related deaths in the county.

A 2019 count of homeless people by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) found that there were nearly 24,000 people without homes in Oregon and Washington. Of those, about 41% were completely unsheltered, meaning they, in particular, will be at risk as the temperature rises. Heading into the peak of this latest heat wave, Multnomah County, home to Portland, is offering transportation services for the homeless population and deploying mobile outreach teams to bring people water and other supplies.

2. People who work outdoors

After California, Washington has the second highest number of farmworkers in the nation—nearly 230,000 in all. Many of these farmworkers are involved in the production of labor-intensive crops such as fruits and tree nuts. While all outdoor workers should be empowered to take precautions when temperatures rise, farmworkers have a particularly high risk of dying from heat-related causes.

Only two states in the nation currently have enforceable heat protection standards on the books for outdoor workers—California and Washington. With those standards in place, Washington-based employers will need to ensure that they are providing their employees with the rest, hydration, and supervision required for staying healthy and safe over the course of the next week.

Notably, Oregon OSHA is considering joining California and Washington in getting a rule in place for protecting outdoor workers from extreme heat and wildfires, something public health, environmental, and social justice advocacy groups have been pushing for in the wake of last year’s devastating wildfire season in the state.

3. People who have not gotten the COVID-19 vaccine

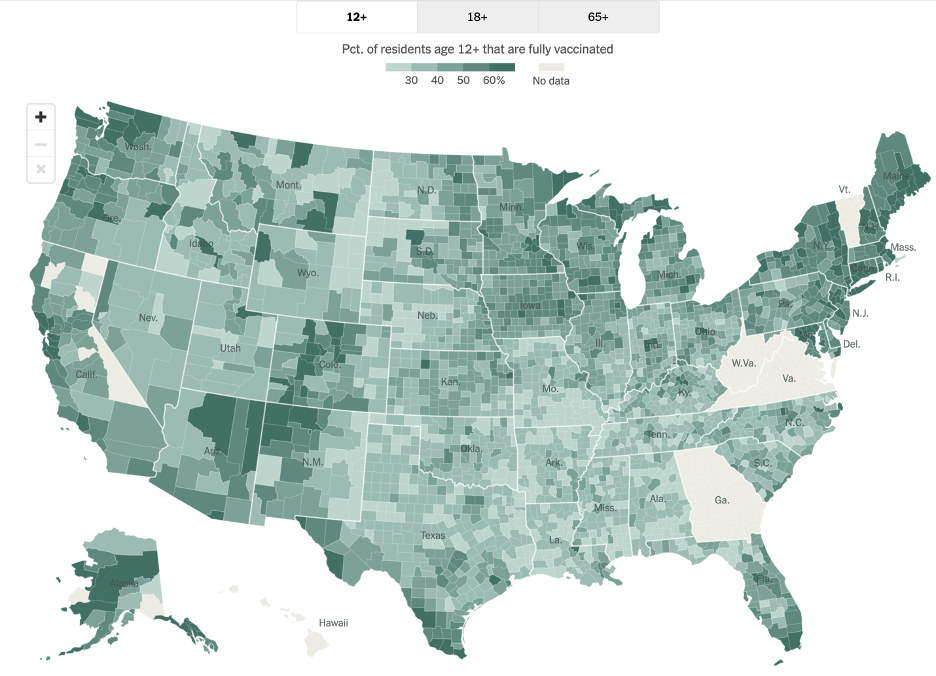

With air conditioning rates low in Pacific Northwest homes, people may end up seeing relief from the heat at public cooling centers. Last summer, many facilities that typically serve or function as cooling centers, such as public libraries and movie theaters, were closed due to the pandemic. This year, however, with many such facilities open again, unvaccinated people may find themselves at heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 if they’re seeking refuge from the heat.

Vaccination rates in the eastern halves of Washington and Oregon tend to be lower than the national average. In many counties, 33% or less of the total population is fully vaccinated compared with 54% of the US population as a whole.

4. People who are young or elderly as well as those with pre-existing conditions

These groups of people are at heightened risk when it comes to heat waves for a variety of reasons. In addition, some commonly prescribed medications can affect thermoregulation or heighten the risk of dehydration. People within these groups should make sure they have a plan in place for cooling off during the heat wave. And if your friends, neighbors, or loved ones include people in these groups, make a plan to check in on them to make sure they’re staying cool and safe over the next few days.

Climate change will make extreme heat more frequent in the Pacific Northwest…will legislators rise to the challenge?

With continued emissions of heat-trapping gases, climate change is expected to make extreme heat more frequent and more severe. While the Pacific Northwest is not in danger of developing a Texas-like climate anytime soon, the region is expected to see the number of hot days increase even in the next few decades.

In this sweltering present moment and with the knowledge that a much hotter future is in store, Oregon legislators are just a few days from wrapping up their 2021 legislative session and have two climate-related bills to take up.

HB 2021 (100% Clean Energy for All) will ensure that 100% of Oregon’s electricity is supplied from clean and carbon-free sources by 2040. The legislation will also prevent construction of any new natural gas power plants within the state, provide $50 million for community-based clean energy projects, and require good wages and benefits for workers on larger renewable energy projects. Critically, HB 2021 is being led by the Oregon Clean Energy Opportunity Campaign, which is comprised of frontline communities, EJ, and tribal organizations. This has helped to ensure that the legislation works for communities that have been overlooked for far too long.

HB 2842 (Healthy Homes) will create a Healthy Homes Program and provide $10 million to a Health Homes Repair Fund to assist low-income households and environmental justice communities with repair and rehabilitation of homes, including energy efficiency upgrades, air filtration systems, improved fire resilience, and abatement of health hazards like mold and lead.

With more Oregon homes needing to be able to keep occupants safe in the face of increasingly severe heat, these two bills will go a long way to ensuring that people are able to stay cool using clean energy sources at home. Much is at stake in these last few days of the legislative session: If legislators fail to take up or advance these bills, there won’t be another opportunity for climate legislation in the state until next year. If you live in the Pacific Northwest, stay safe this week and have plans in place for how you’re going to cool off–whether that’s at home, at a pool, or at a cooling center—and how you’ll be checking in on neighbors, friends, and family members in higher-risk groups. And if you’re in Oregon, I’d urge you to do all of those things and contact your legislators to encourage them to support HB 2021 and HB 2842.