UPDATE February 16, 2022: While 59% of independent shareholders supported the Green Century proposal calling on Tyson to reduce its use of plastic packaging, the resolution was ultimately shot down by Tyson family shareholders. Though not surprising, the outcome is another indication of the company’s antagonism to serious sustainability actions. UCS will continue to press Tyson Foods to improve its record on farmland sustainability, worker justice, and farmer fairness.

This week, the nation’s largest meat and poultry company will hold its annual shareholder meeting. On a secure Zoom call from Arkansas, Tyson Foods investors will vote on a modest proposal to improve sustainability in Tyson’s operations by studying the amount of plastic packaging the company uses. That proposal will almost certainly be voted down. At the same time, a new Union of Concerned Scientists analysis has concluded that the company could and should do much more to reduce its harmful impacts on our air, water, and land.

“Big Chicken” = big polluter

Tyson’s tendency to cheat farmers and to exploit and endanger workers has prompted considerable scrutiny, and rightfully so. But the meat and poultry giant also has a massive environmental impact. To understand why, first you need to appreciate just how big Tyson Foods and its supply chain are.

According to the company’s website, Tyson produces 20 percent of all US beef, pork, and chicken. To produce and sell that much meat, Tyson slaughters and processes truly unimaginable numbers of animals. Based on Tyson’s reported weekly production capacities and utilization rates, we estimated that the company processed approximately 6 million head of cattle, 22 million hogs, and nearly 2 billion(!) chickens in 2020.

The 123 processing plants that do this dirty work produce and discharge a lot of waste. A 2016 study analyzed publicly available toxic discharge data from the US Environmental Protection Agency and named Tyson the second-biggest polluter of US waterways from 2010 to 2014. The study found that Tyson and its subsidiaries’ processing plants dumped more than 104 million pounds of pollutants into waterways during that period. And multiple states have sued Tyson in recent years for spills or improper discharge of animal waste and other pollutants. These include Alabama, where an estimated 220,000-gallon spill caused one of the largest fish kills in the state’s history in 2019—a case Tyson settled in 2021 for $3 million. Tyson also settled another pollution case with the state of Missouri and paid a $2 million fine for a second Clean Water Act violation in that state. Oklahoma has been waiting 16 years to collect damages and injunctive relief for hundreds of tons of stored and disposed poultry waste within the state’s watersheds, a case popularly (and sadly) known as the Bus Loads of Lawyers case.

But spills and illegal discharges from Tyson processing plants are just the tip of the iceberg. There is another ongoing and completely unregulated source of pollution for which the company is ultimately accountable.

Tyson’s massive grain supply chain

Remember those billions of animals Tyson processes every year? While they’re living, they have to eat. And what they eat, primarily, is vast quantities of corn and soybeans. Corn is the most widely used feed grain, but livestock and poultry eat a lot of soybeans, too—more than 70 percent of all soybeans grown in the United States.

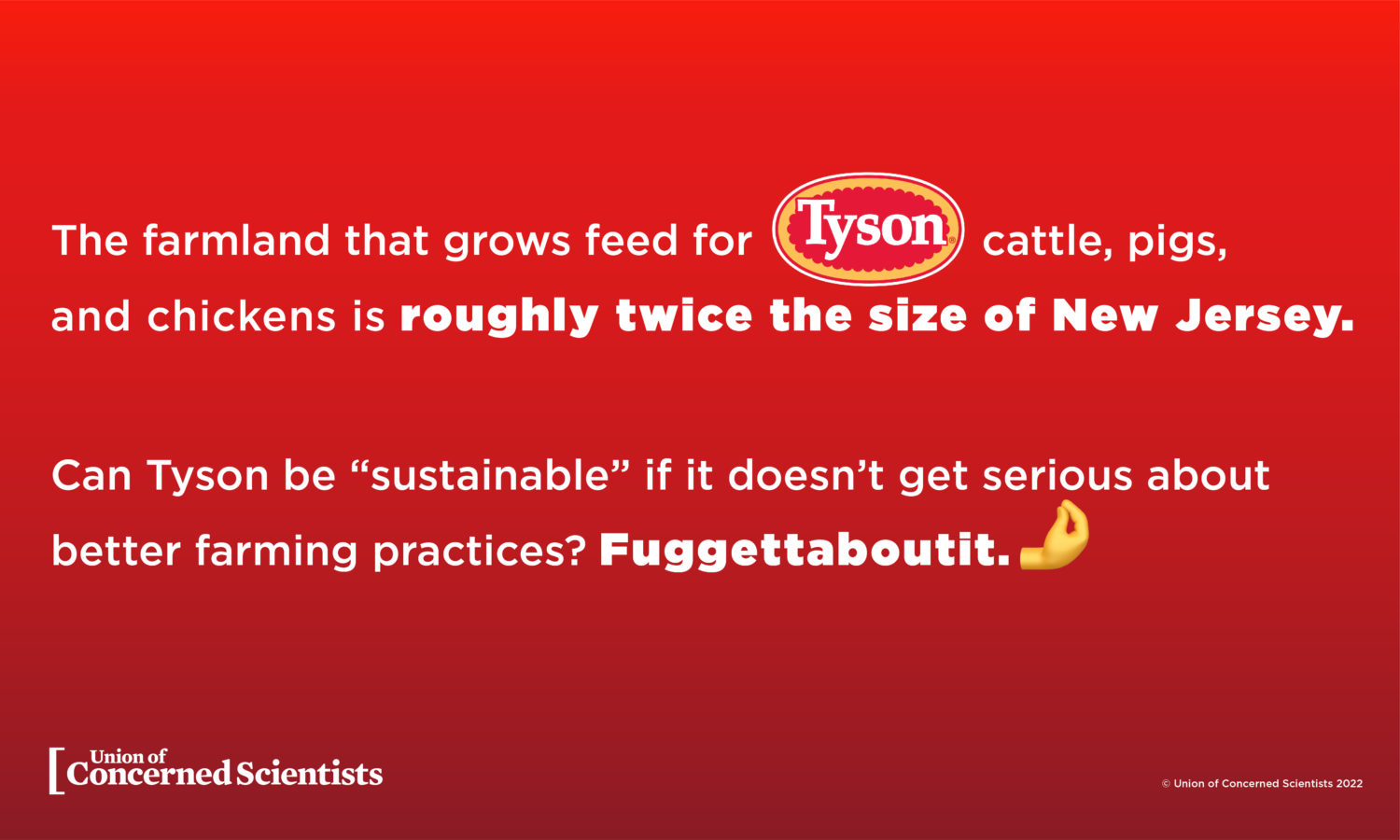

Growing feed for Tyson’s supply chain takes a great deal of farmland. We estimated the acreage used for all this corn and soy, and it’s big. As in, up to 10 million acres big.

While we can’t say for sure, we can assume that grain production on those 10 million acres uses prevailing farming practices that a) contribute to soil erosion and fertilizer runoff causing coastal dead zones, b) release heat-trapping gases that drive climate change, and c) leave farmland and surrounding communities vulnerable to extreme weather. In short, those 10 million acres can cause substantial environmental damage.

Tyson keeps punting on sustainability

Though our estimate of Tyson’s 10-million-acre “farmland footprint” is new, the issue of its impact on farming practices and water pollution has been brought to the company’s attention many times. Again and again—in 2017, 2018, and 2019—investor groups brought these concerns to Tyson. But each time, shareholders voted the resolutions down. In 2018, the company trumpeted a commitment to shift 2 million acres of cropland—just 20 percent of its total footprint—to more sustainable practices by 2020, but it hasn’t followed through. As of 2021, the company had enrolled a mere fraction of this acreage into a pilot program, and it is unclear how sustainable the management of that fraction really is. Meanwhile, the company has punted the original 2-million-acre commitment to 2025. (Because COVID, it says.)

Instead of taking sustainability seriously, in 2019, Tyson hired a chief sustainability officer. His name is John R. Tyson, the founder’s great-grandson. For failing to meet the company’s feed sustainability goal, he was paid a cool $13.7 million in total compensation in fiscal year 2021. I wonder how much they’ll pay him to not study plastic use this year.

I can say that because, ahead of this year’s annual meeting, Tyson executives have already officially urged shareholders to reject the plastic resolution. Just like those earlier water pollution proposals, the plastic resolution will go down in flames because that’s what the Tyson family wants. You see, the founder’s descendants have a lock on shareholder voting through a system known as a dual class stock structure. Essentially, Tyson issues two different classes of shares, with one class having more voting power and earning better dividends than the other. Members of the Tyson family own the better, Class A shares. (The dual class system was challenged by investor groups in 2020 and 2021, but—surprise, surprise—the family voted down such a change.)

At this week’s annual meeting, shareholders no doubt will hear about how the company’s first-quarter profits nearly doubled, while they vote to approve sky-high executive compensation for another year. Last year, according to the meeting’s proxy statement, the top three execs pulled in a total of $37.2 million, including a $6 million severance for the CEO who left abruptly mid-year.

Regulators must curb Tyson’s power

If you’re wondering how Tyson has amassed the power to enrich itself while making so many things worse, the answer is unchecked consolidation. Our 2021 report Tyson Spells Trouble for Arkansas highlighted how the company has used mergers and acquisitions to dominate the poultry market in its home state, controlling activity up and down the chicken supply chain. That includes milling grain for feed—in 2018, Tyson produced around 10 million metric tons of feed in a total of 32 feed mills throughout North America—enough to make it the ninth-largest feed producer in the world. Lax enforcement of antitrust laws over decades has allowed Tyson Foods to grow to a size and power that is bad for everyone else. Its massive farm footprint and outsize environmental impact are just one indication that the company is too big. It is time for regulators to rein it in.

My colleague and economist Rebecca Boehm made a case recently in Tyson’s hometown newspaper for bold policy action to curb its power and that of other big processors and to restore competition to the meat and poultry industry. Earlier this year, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced an unprecedented $1 billion in investments to spur competition, and just last week, the USDA and the Department of Justice launched a portal through which farmers can file antitrust complaints. And there is more the Biden administration can do, including prosecuting antitrust actions more aggressively and creating new rules to keep the Tysons of the world in check.

Tell them to do it: take action today.