The first half of the Atlantic hurricane season has been unsettlingly quiet, but it’s not over yet—and experts continue to anticipate a busy few months to come. Beyond the widespread and catastrophic domestic consequences such storms can bring, this year’s hurricane season carries with it heightened international consequences, too, given the threat that these storms pose to Gulf Coast fossil fuel infrastructure and the degree to which that infrastructure is tightly intertwined with the global response to Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

While the epicenter of the war and its horrors has remained trained on and in Ukraine, Russia has also leveraged its position as a major fossil fuel exporter to fund its war efforts and to manipulate and threaten others, including countries across Europe that have long relied on Russian supplies of gas.

In response, Europe has scrambled to replace flows and decouple this dependence, in part by shifting away from gas to clean energy alternatives, in part by increasing local gas production, and in part by turning to imports of liquified natural gas, or LNG—including from the US.

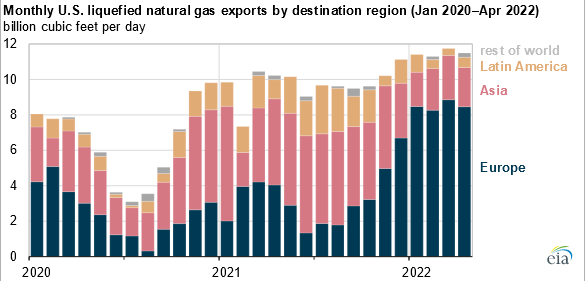

Over the first four months of 2022, nearly half of all European gas imports came from the US, with the region growing to account for three-quarters of all US LNG exports compared with just a third the year prior.

This shift has coincided with the nation’s rapid rise in LNG exports overall, surging from zero at the start of 2016 to becoming the largest global LNG exporter in 2022—and even more export projects are anticipated to come online over the next few years.

The short-term flexibility enabled by LNG has yielded benefits in the quest to undercut Russia’s dangerous position of influence in the European gas market. However, a deepening, more permanent commitment to expanding LNG—both in the US for exports and Europe for imports—threatens costs and risks, each of which demand close examination before such large-scale and long-lasting investments are made.

Not least among these include the fundamental misalignment of building out long-lived fossil fuel infrastructure that is entirely incompatible with long-term climate commitments—nor the fact that on both sides of the Atlantic, such long-lived infrastructure will first take multiple years to construct. Which means that in exchange for more carbon dioxide and more methane worsening climate change, plus more local air pollution and more environmental degradation burdening surrounding communities, Europe will receive neither the near-term nor long-term energy fixes it needs while the US will be saddled with the costs and consequences of buildouts nobody will soon want.

And then there are the hurricanes

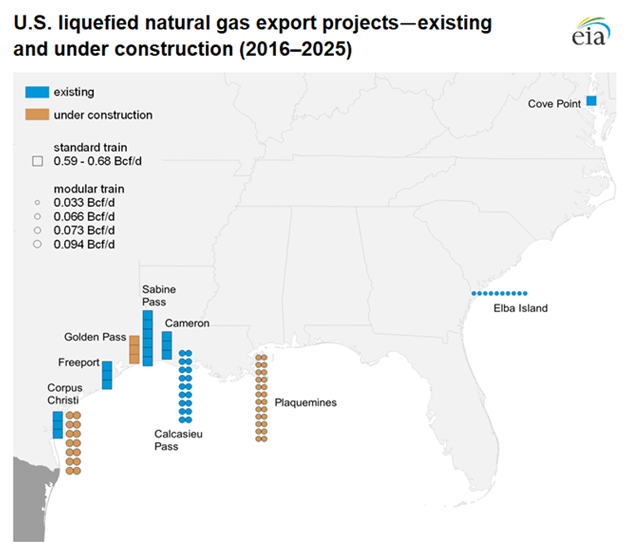

The bulk of US LNG export facilities (and proposed facilities) are clustered along the Gulf Coast, and much of the gas that feeds those facilities comes from nearby inland reserves, from New Mexico to Texas to Louisiana and beyond.

This means that when hurricanes come roaring inbound, everything from extraction to processing to liquefaction to shipping lanes are all at risk of disruption.

This is not a hypothetical.

In recent years, multiple hurricanes have resulted in disruptions to the LNG market, sometimes as brief outages and sometimes curtailing flows for long after, with impacts stretching across the supply chain. For example, Hurricane Laura (2020) resulted in a two-week disruption at the Sabine Pass LNG export facility but well over a month at Cameron LNG, the latter of which was sidelined by an accumulation of incidents, including to external supplies of electricity as well as required repairs and dredging to the associated shipping channel. Hurricane Ida (2021), on the other hand, resulted in a major and long-lasting curtailment of offshore gas production.

Yet none of these storms have come in the midst of a war tightly interconnected with global energy markets. What’s more, the market is already untenably tight.

On the supply side, a June explosion at the Texas-based Freeport LNG facility knocked nearly 20 percent of US LNG export capacity offline, sending immediate shockwaves throughout the LNG market. When the latest status check pushed back the initial restart date to November, markets again convulsed.

Meanwhile, Europe continues to claim as much LNG as it can from redirected global flows—primarily from Asian countries holding back on purchases, though that is starting to shift. Surging gas prices alongside overall scarcity in supply have had rippling implications for the European economy, sending electricity prices soaring, motivating plans for energy rationing, shutting down industrial facilities, driving down economic expectations, and stressing personal and national budgets. Other countries historically reliant on the spot market have been priced out entirely, such as Bangladesh, which is now experiencing repeated rolling blackouts. More supply-side disruptions will only exacerbate these crises.

And there, again, loom hurricanes.

Hurricanes that are heightening in severity, increasingly rapidly intensifying, bringing record-breaking compound flooding, and all riding in on ever-rising seas—all of it bad, all of it worsening, all of it placing critical infrastructure at risk, and none of it sufficiently accounted for.

Which means more white-knuckled volatility in the gas markets over the next few months, and, perhaps more critically, every year onward over the multi-decade life of these infrastructure investments. Because there are no reprieves to hurricane season, and even if LNG facilities end up sufficiently fortified themselves, they and the broader market will still be vulnerable to disruptive climate impacts occurring upstream and downstream.

In light of all this, it beggars belief that European countries would contemplate initiating multi-decade contracts with new US facilities located straight in the tracks of annually repeating disruption. And for the US to continue to allow these facilities to be built out, vulnerable as they are and will increasingly be.

In Europe, in the US, all across the globe, we need energy transition solutions that are robust across the here-and-now and the longer term, that put us on the path to a sustainable, resilient clean energy future, not ones that directly exacerbate an already untenable state.

There are not easy decisions ahead, but clearly, clearly: there are better and there are worse. Let us at least stave off the worst.