2023 is forecast to be an eventful year for climate litigation: legal actions aiming to hold polluters accountable for their role in climate change, ensure that international treaties and agreements are followed, and protect human rights that are being negatively impacted by climate change. I’ve been working in this space for a short three years, but in that time, I’ve witnessed incredible change and development. Climate litigation has been rapidly growing over the last 5 years with thousands of cases currently filed across the world in local, state, national, and international courts. With recent wins in the courts and a growing community of legal practitioners, 2023 will be filled with more advances in this work. Here are my predictions for a few things we’ll see this year.

1. Cases will start to be heard on their merits in the US (finally!)

In 2023 I believe that ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, Chevron and others will run out of legal stall tactics, and communities across the nation will get their day in court. Nearly 30 states, cities and counties in the U.S. are taking major oil and gas corporations to court, but most of these cases have been tangled up in in jurisdictional battles. The fossil fuel industry has been using these technical legal battles to slow accountability, but they are on their last appeals in the U.S. legal system.

If the industry continues to delay the courts there is space for the current administration to step up. In 2023 the Biden administration has a unique opportunity to support groundbreaking climate litigation and follow through on President Biden’s campaign promise to “strategically support” climate change-related lawsuits against polluters. We are calling on the Biden administration and the DOJ to side with communities and ensure that communities get their day in court this year.

2. We’ll see new and exciting legal approaches to accountability across the globe

The legal community has been building strategic approaches for climate accountability and—while many of these tactics will be replicated in new places—2023 will also bring never before tried legal approaches. We got a taste of this towards the end of 2022 when sixteen jurisdictions in Puerto Rico filed a first-of-its-kind climate racketeering lawsuit alleging that ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, and others colluded to publicly deny the climate risk of their products. Racketeering charges evoke images of the Mafia and organized crime, but since the 1970s, racketeering charges have been used to address corruption and fraud by large actors, including the tobacco industry. Puerto Rico’s racketeering case is an example of new thinking from new places that will flourish in 2023.

Where else might litigation go this year? I predict three key areas of growth:

- Innovative greenwashing lawsuits – these cases could dig deeper into annual reports and archived documents to really look at environmental claims and “net zero” statements from several industries, including clothing companies, the auto industry, agribusiness, and Big Oil. Some of these cases will be informed by government actions, such the U.S. House Oversight and Reform Committee investigation into oil and gas industry greenwashing and climate disinformation.

- More cases against corporate actors – Today, many climate cases address concerns about government inaction on climate change, but in 2023, I think we could see a wave of corporate cases emerge. There have already been some big wins on this front in the Netherlands, where a Dutch court ruled that Shell must cut its carbon emissions, and in Australia, where a new coal project was rejected due to emissions and human rights concerns. These cases represent different legal approaches to corporate climate litigation, and they are likely just the beginning.

- Climate change will be discussed in the world’s highest court – An upcoming UN vote for the International Court of Justice (ICJ) Advisory Opinion on climate change led by the nation of Vanuatu has the potential to inform climate litigation across the world. The advisory opinion would seek clarification on the obligations of nations under international law to protect people against the adverse impacts of climate change. I’m watching this advisory opinion in the ICJ because it could help to better connect scientific evidence on climate change to the courts.

3. Advances in science will strengthen existing and inform new cases

The current rise in climate cases is closely tied to scientific advances. Last month, I published an article with my colleagues that identified key research priorities to inform climate litigation. During 2023, with a clear understanding of research needs, a growth of scientific community engagement, and improved communication around litigation, we will see significant growth in climate litigation-relevant research.

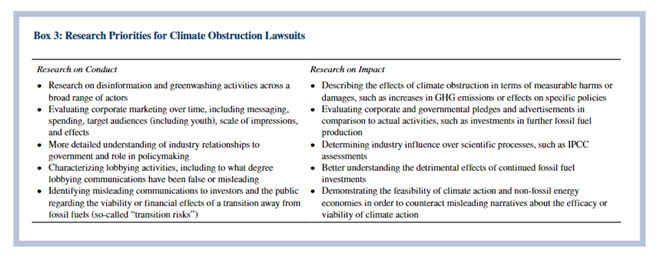

Our article, Research Priorities for Climate Litigation, analyzed interviews with climate litigants from across the globe and found a pressing need for more research in three main areas: climate change detection and attribution, climate disinformation, and obligations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

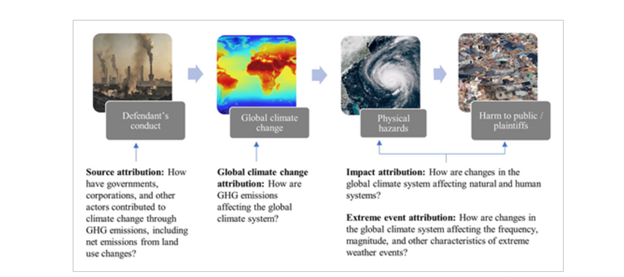

Climate detection and attribution: It is an exciting time of growth for climate detection and attribution research. Today, detection and attribution science research are increasingly accurate at finer spatial and temporal scales. Research is needed that explores additional climate impacts in geographically diverse areas. This work is particularly important because climate detection and attribution research can play an important role in establishing the causal link between a defendant’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and climate harms, as seen in the figure below.

Obstruction of climate science and action: Earlier this month, an impressive research article published in Science dug into ExxonMobil archival documents and found that Exxon accurately predicted global warming dating back to the early 1970ss. This study shows that, without a doubt, Exxon scientists understood the implications of burning fossil fuels but corporate decisionmakers failed to act in alignment with their own scientific knowledge. ExxonMobil was on the cutting edge of climate science—but instead of informing the public, the company designed and funded deliberate disinformation campaigns. This is just one example of research relevant to climate obstruction litigation. Below are the research priorities in this area we identified in our paper.

Obligations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: There is a growing body of physical, social science, and legal scholarship on carbon budgets to help inform carbon emission levels for countries and corporations. The courts depend on this type of research to determine carbon emissions reductions, these decisions, however, are very complex. Through climate litigation courts will have to decide how to define emission reductions in reference to (a) historical, current, and/or future emissions; (b) use or production-based emissions; (c) total or per capita emissions; or (d) a hybrid approach which combines emissions accounting methods. New scientific research is needed help to ensure the courts really understand this complex landscape.

This year promises to be filled with new litigation and meaningful movement for ongoing work, all informed by robust science. The opportunities and prospects for climate lawsuits have improved as researchers have generated new evidence and, with a clear understanding of gaps in research, can progress even further. As we move into 2023, I’m feeling a renewed energy to focus on community and growth around climate litigation.