Following the wide coverage of a suspected Chinese spy balloon in US airspace earlier in February, Senator Jon Tester (D-MT) and others have proposed legislation that would seek to limit foreign ownership of US farmland, targeting China, Russia, and other “adversaries” of the US government. But how much land do foreign entities really own in this country? And does that tell the whole story of the threat to our food supply and national security that emerges when farmland becomes a commodity or an investment opportunity?

Corporate and private land ownership

Farmland has always been a lucrative investment for the rich. Millions of acres owned by wealthy individuals and corporations (those not actively involved in farming) are leased out.

According to the last Census of Agriculture in 2017, agricultural land is still primarily owned by families and individuals (201.5 million acres of cropland and 223.8 million acres of pastureland). The remaining 3.1 million acres of private cropland and 6.4 million acres of private pastureland are held by partnerships, family corporations (in which a single family and close relatives hold a majority of shares), and industrial agricultural corporations.

As land becomes more expensive, wealth becomes a deciding factor in who gets cut out versus who has the opportunities and the means to procure land. For instance, Bill Gates made headlines a few years back when he became one of the United States’ largest private landowners. For high-net-worth individuals like Gates, land is generally an investment rather than a means of livelihood.

Foreign-owned agricultural land

As of 2021, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported that foreign persons and entities held an interest in 40.8 million acres of US agricultural land—about 4.5 percent of the total. Texas has the largest amount, at approximately 5.3 million acres. Maine has the second-largest amount, with just over 3.6 million acres, followed by Colorado, with approximately 1.9 million acres. Foreign investors from China own about 383,935 acres of land (both agricultural and non-agricultural), which comprises about 1 percent of all foreign-held acres. Investors from Russia and Iran own even less land, totaling 73 acres and 4,324 acres respectively. The countries owning the largest shares of US farmland are actually Canada, the Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Germany.

Reports suggest that data collected on foreign land ownership are incomplete, may contain errors and omissions, do not track sales of foreign-held US farmland, and thus may not reflect reality. There is currently no prohibition on foreign entities buying US land. Federal law requires foreign persons and entities to disclose to the USDA information related to ownership of US agricultural land. There is also a patchwork of regulations and disclosure requirements at the state level, and some states limit or have proposed banning certain foreign entities from acquiring agricultural land. The California legislature recently passed a bill restricting foreign land ownership, but it was vetoed by the governor.

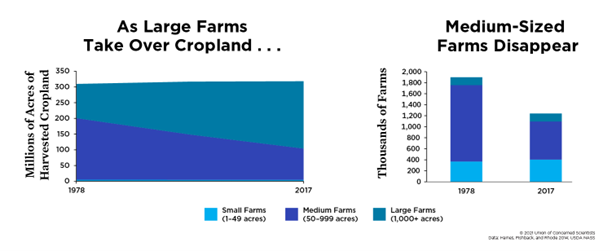

Cropland has shifted to larger farms

Foreign-owned agricultural and non-agricultural land represents less than 5 percent of the 895.3 million acres of land currently under cultivation in the United States. A bigger threat to our food system exists domestically: land consolidation, a trend that has been ongoing for the last few decades. Consolidation happens when large farms acquire the land of smaller farms, leading to the predominance of increasingly large farms.

According to USDA data, in the 1980s more than half (57 percent) of all US cropland was operated by midsize farms (100 to 999 acres), while 15 percent was operated by large farms (at least 2,000 acres). Over the next three decades, cropland shifted toward larger operations, and by 2012, midsize farms held only 36 percent of cropland.

Today, large farms with revenues of at least $1 million contribute upwards of 42 percent of total US farm production, which suggests that a significant portion of our food and commodities comes from large farms. Although the percentages of land held by large farms and foreign investors are comparable, it’s important to note that not all foreign-held land is part of large farms.

Why is consolidation a problem?

Midsize farms are rapidly disappearing, catalyzed by changes in federal farm policy that favor large farms. The commodity-based farming system in this country rewards size—the bigger the farm, the higher the profit.

Arguably the single biggest effect of land consolidation is that it excludes new and beginning farmers and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and other people of color) farmers from owning land, entering the profession, and creating generational wealth. Farmers of color, especially Black farmers, have faced the disproportionate burden of consolidation compounded by a history of systemic racism. In the early 1900s, more than 900,000 Black farmers owned an estimated 20 million acres of land. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, Black-owned land had dwindled to about 4.7 million acres, just 0.5 percent of the US total, while the number of Black farmers dropped from 14 percent in 1920 to just 1.4 percent. UCS found that in states where land consolidation is the highest, the loss of Black farmers has been the most severe, costing Black communities more than $320 billion in wealth.

Large farms also amplify the monocultural model of agriculture, in which a single crop (typically corn or soybeans) is grown over a huge tract of land year after year using vast quantities of fertilizers and pesticides. The growth of monoculture amplifies the environmental problems that come along with it, resulting in degraded soils and water quality.

As midsize farms get pushed out, the price of land rises. In the Midwest, where harvested cropland on large farms has more than quintupled in recent decades, the value of this land has also risen simultaneously. According to USDA NASS data, in 2022 alone the Corn Belt states witnessed an average increase in land value of 15.3 percent.

Farmland consolidation amplifies poverty and inequality—what can be done?

Farmland consolidation means that a few corporate entities have control over a majority of what’s grown, how it’s grown, and what ends up in grocery stores, giving them considerable power over our food security. Their ability to spend millions of dollars on lobbying also gives them considerable influence over food and farm policy. Ultimately, “Big Ag” can dictate food prices and drive them higher, as we’ve witnessed with meat and poultry prices over the last several years, and most recently with the egg-price crisis. So farmland consolidation is bad for farmers, bad for food sovereignty, bad for food security, and indeed, bad for our national security.

Negotiations are starting in Congress on the next food and farm bill, which could incorporate other pieces of legislation like the Justice for Black Farmers Act that aims to reverse the history of land consolidation and increase Black farmers’ access to land. Instead of the current food system that exclusively works in favor of large landowners and producers, the upcoming food and farm bill can take back control from Big Ag. Join us this year in advocating for an equitable system that works for underserved farmers, new and beginning farmers, and all of us.