After several years of drought and tinder-box conditions, abundant rains over the past winter have those of us who live in the western United States hoping for a year with less wildfire activity this summer and fall than we’ve had in recent years. The latest seasonal outlook from the National Interagency Fire Center largely points to such a reprieve—at least for the next few months.

This year’s potential reprieve is the perfect time to ramp up wildfire resilience-building efforts that would prepare us for future wildfire seasons.

Over the past 30-40 years, wildfire data show a clear signal from climate change: As global temperatures have warmed over the past several decades, western wildfires have worsened by nearly every metric, from the number, size, and severity of fires to the length of wildfire season.

In a world with a changing climate, what does a typical wildfire season in the western United States look like? For what should we be prepared?

Let’s dive into western wildfires by the numbers.

Wildfire activity ramps up during Danger Season

As spring turns to summer and the days warm up, the Northern Hemisphere enters the period known as Danger Season, when wildfires, heat waves, and hurricanes, all amplified by climate change, begin to ramp up. In the western United States, the start of Danger Season is marked by the shift from the wintertime wet season to the summertime dry season. While wildfires can and do occur all year round, this shift from cool and wet to warm and dry marks the start of wildfire season in the region.

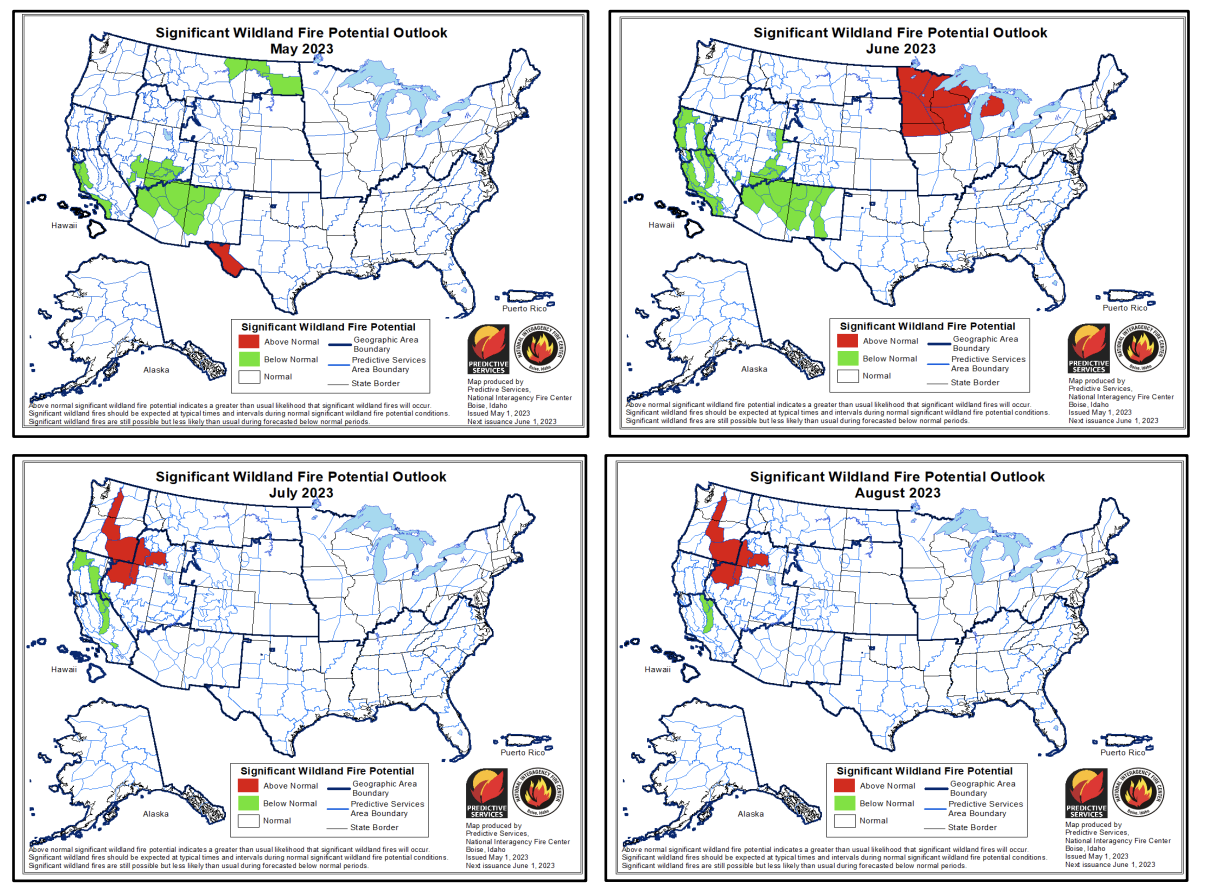

According to the latest seasonal outlook from the National Interagency Fire Center, the exceptionally rainy and snowy conditions the west experienced during the winter of 2022-2023 are translating to below-average to normal levels of wildfire risk across most western states at least through August. That said, above-normal activity is expected for parts of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Nevada. Some scientists are also raising concerns that all the young grasses and other plants that have sprung up as a result of the wet weather could quickly turn into dry kindling for wildfires as the dry season wears on into late summer and fall.

Wildfires are worsening across the western US and southwestern Canada

There are many different ways to measure wildfire activity, but by almost any metric, wildfires across the western US and southwestern Canada are worsening. Reliable, consistent wildfire metrics across the region started to become available in the mid-1980s. Here’s what the trends show.

The number of fires per year has increased.

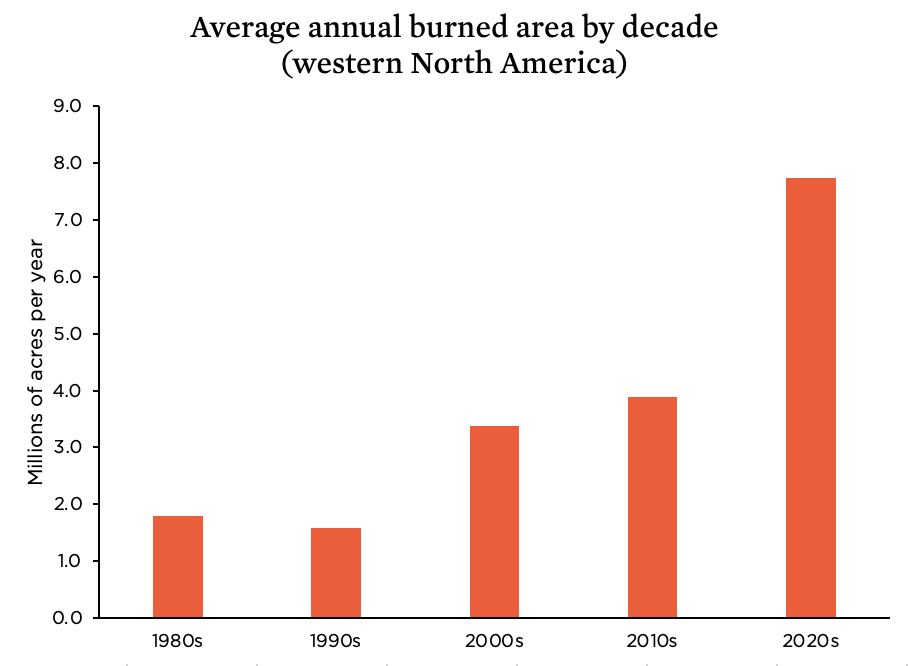

From 1984 to 1999, the region experienced an average of roughly 230 fires per year. From 2000 to 2021, the average was more than 350 fires per year.

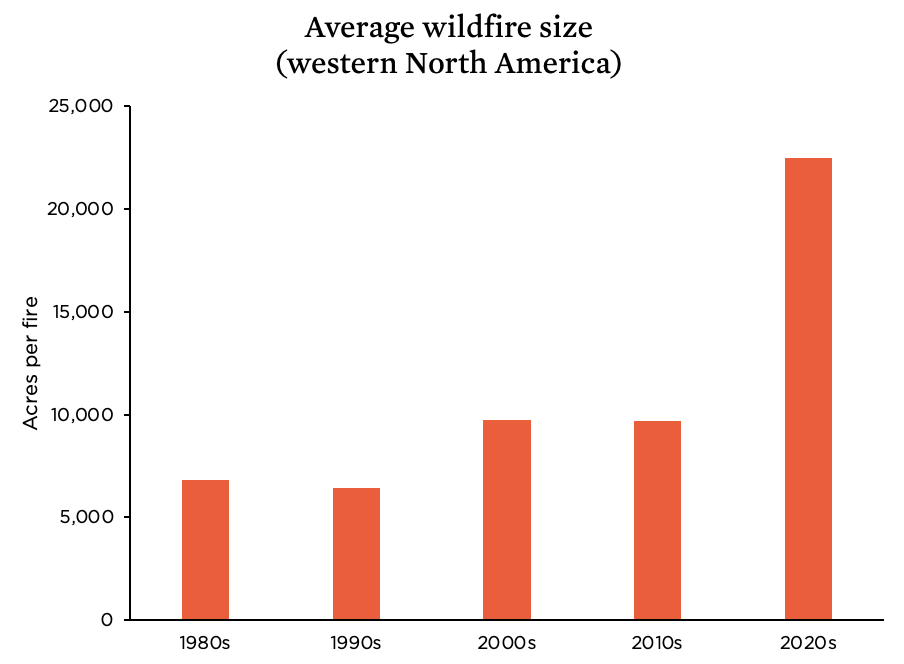

At the same time, the average size of those fires has increased. Two years, 2020 and 2021, stand out as having an average wildfire size of more than 20,000 acres, an average that likely reflects California’s August Complex and Dixie Fires that burned during those years, as each exceeded one million acres in size. They were the first fires on record in the US to do so.

Even without those years, however, average fire size has been trending upward. During the 1984 to 1999 period, the average wildfire burned about 6,600 acres. During the 2000 to 2021 period, the average was nearly 11,000 acres—a 65% increase in size.

Not surprisingly, increases in both the number of fires and the average size of those fires has resulted in an upward trend in the area burned by wildfires each year.

While there’s variation from place to place, many of these trends hold true for individual states as well.

For example, the average size of wildfires in New Mexico has grown and the total acreage burned in the 2010s was nearly double that burned in the 1990s. In fact, the state’s largest fire on record, the Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire, burned just last year.

Wildfires are worsening in other ways, too. Across western US forests, the length of the annual wildfire season has increased by more than 80 days; fires are burning at higher elevations; and the area burned at high severity, which influences an ecosystem’s ability to recover after a fire, has increased. While most fires in this region still occur during summer and fall months, spring and winter fires are increasingly the norm (though remain notably smaller than their summer and fall counterparts).

Notable 21st century wildfires

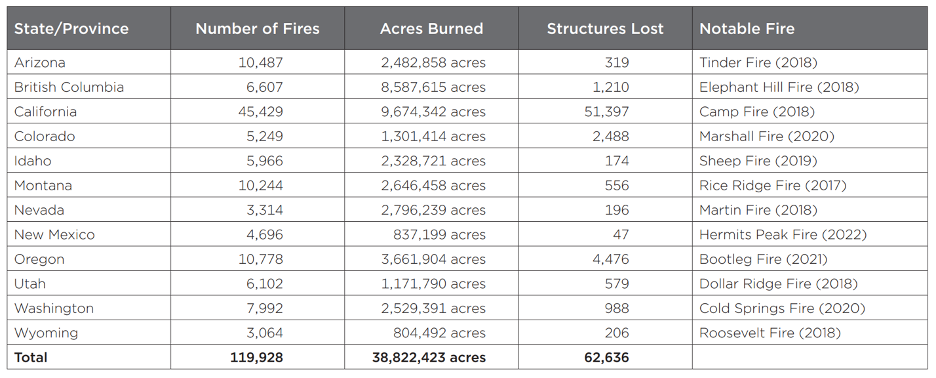

Since 2017, many western states have experienced record-breaking wildfires. In Colorado, for example, the state’s three largest wildfires on record all occurred in 2020. In September of the same year, wildfires burned more than 500,000 acres in Washington state in just 36 hours. And California’s eight largest wildfires on record have all occurred since 2017.

In addition to millions of acres of land scorched by fire, entire towns and communities have been decimated in recent years, and dozens have lost their lives.

In 2018, California’s Camp Fire burned the town of Paradise nearly entirely to the ground and claimed the lives of at least 85 people. Five small towns in Oregon—Detroit, Blue River, Vida, Phoenix, and Talent—were lost to the so-called Labor Day Fires in 2020. And in 2021, the Lytton Creek Fire wiped out the village of Lytton, British Columbia, destroying hundreds of homes.

All told, between 2017 and 2021, nearly 120,000 fires burned across western North America, burning nearly 39 million acres of land and claiming more than 60,000 structures.

Wildfires indirectly affect millions of people

The impacts of wildfires reach well beyond the people, communities, and ecosystems that are directly affected by flames. Wildfires have consequences for public health, water supplies, and economies long after a fire is extinguished. Mounting research is showing exposure to the fine particulate matter in wildfire smoke is responsible for thousands of indirect deaths, increases to the risk of pre-term birth among pregnant women, and even an increase in the risk of COVID-19 illness and death.

Surprisingly, some of the biggest increases in wildfire smoke exposure in recent years are in the Great Plains region, from North Dakota to Texas.

In addition to their impact on air quality, wildfires can disrupt processes that maintain access to drinking water, including by reducing the ability of soil to absorb water when it rains and sending additional sediment into drinking water systems.

There are other factors affecting wildfire activity

The science is clear that climate change is increasing what’s known as the “vapor pressure deficit,” or VPD, across western North America. When VPD is high, the atmosphere can pull more water out of plants, which dries them out and makes them more likely to burn. VPD also is also a good metric for drought, including the long, 21st century drought the region has been experiencing.

But climate isn’t the only factor behind the west’s worsening wildfires. More than a century of aggressive fire suppression and an even longer period of settler colonial repression of Indigenous burning practices have led to forests that are too dense, too uniform in their species, and without the resistance to fire they once had. Moreover, a lack of affordable housing across the region and the desire for proximity to beautiful, natural places has led to large increases in the number of people living in wildfire-prone areas. Recent research has found that human activities were responsible for starting more than 80% of all wildfires in the United States, while also increasing the length of the fire season.

This year’s wildfire season may offer the western US a chance to catch its breath after several years of record-breaking fires. But with climate change expected to deepen the hot, dry conditions that enable such record-breaking fires, we must be preparing for a future with even more fire.

Carly Phillips contributed to this post.