Fission Stories #159

The fable about the big bad wolf and three little piggies was one of my favorite fables. In some ways, flooding plays the big bad wolf for nuclear power plants.

On March 11, 2011, a tsunami triggered by a large earthquake flooded the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan, overwhelming its protections. The earthquake disconnected the nuclear plant from its offsite electrical power supplies. The tsunami water flooded the emergency diesel generators and many of the battery banks, leaving workers without power for the plant’s dozens of pumps. They were unable to prevent three reactor core meltdowns.

In June 2011, the Missouri River overflowed its banks, transforming the Fort Calhoun nuclear plant temporarily into an island in its stream. The plant’s normal and backup power supplies were challenged by the flooding, but survived in part due to commendable actions initiated by the NRC the previous year.

Fort Calhoun is protected from tsunami threats by being several hundred miles away from sea coasts. Fort Calhoun is protected from river threats by protections taken before, during, and after its immersion test. But just when one might think that Fort Calhoun is fully protected against flooding, the big bad wolf strikes again.

On November 12, 2013, the owner of Fort Calhoun informed the NRC that cracks and other imperfections found in the concrete floor of Room 81 might enable water to seep through. The original design and safety studies for the plant had assumed minimal leakage through the room’s walls and floor.

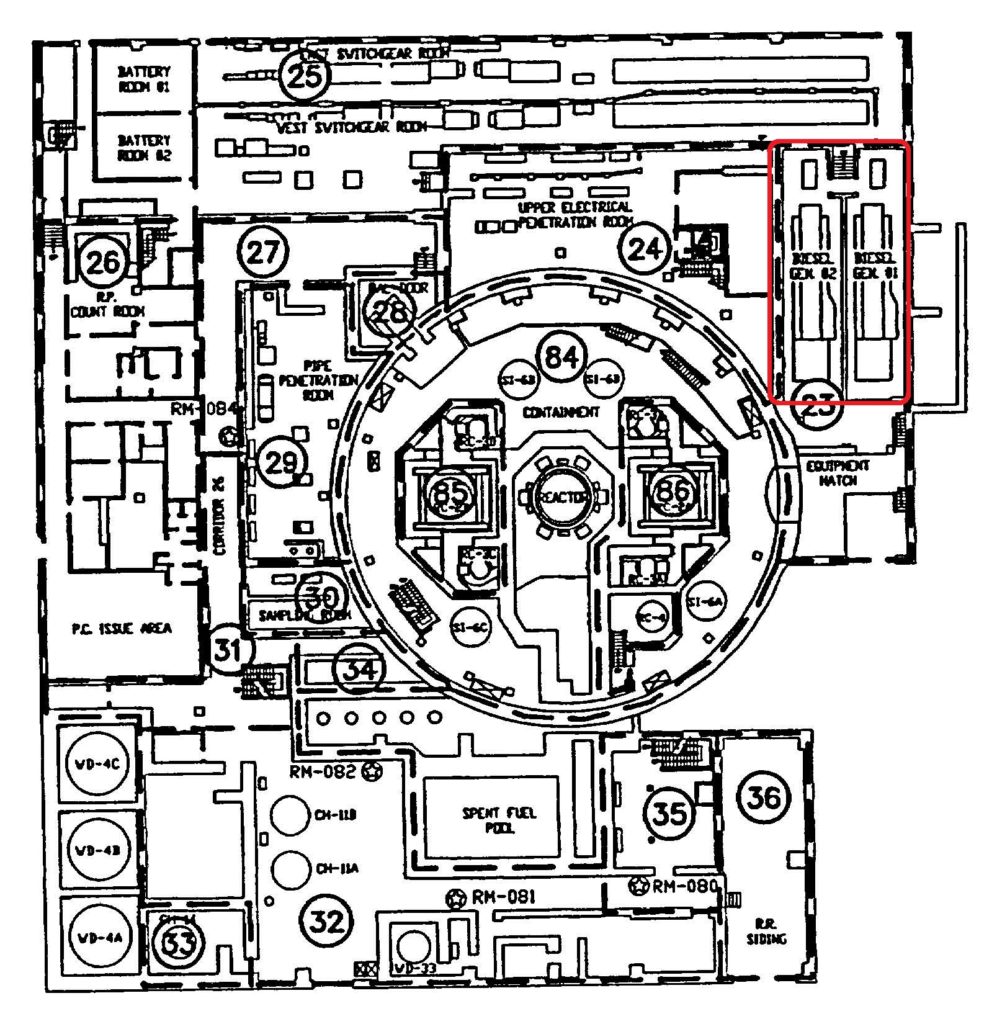

Room 81 is located on the east side of the 1036-foot elevation of the auxiliary building (north is to the left of the diagram). The reactor containment structure is located near the middle of the auxiliary building. As implied by its name, the auxiliary building houses components supporting the reactor’s operation. The main control room is located in the northeast (upper left) corner. The four main steam pipes pass through Room 81 from inside the reactor containment structure on their way to the turbine building to the east.

If one of these steam pipes ruptured inside Room 81, the room would quickly be filled with steam. A valve in the section of the steam line inside the reactor containment structure would close to stop the steam flowing through the broken pipe into the room. But the steam inside the room would cool down and be converted back into water.

So what’s the beef? Instead of pudding on the floor, water seeps through. This pathway appears to provide additional protection against flooding inside Room 81 because it would lessen both the flooding depth and duration. That’s certainly true for components located in Room 81, but…

The East and West Switchgear Rooms are located directly below Room 81 on elevation 1025 of the auxiliary building. Their roofs are Room 81’s floor. Water draining through Room 81’s floor rains into these rooms.

Switchgear consists of electrical breakers, relays, and controls for equipment throughout the plant. Two switchgear rooms are provided for safety—if a fire damages some or all of the equipment in one room, undamaged equipment in the separate adjacent room remains to save the day.

But water leaking through the degraded floor of Room 81 into both switchgear rooms had the potential to disable primary systems and their backups, leaving workers too much like those at Fukushima with dozens of pumps that cannot be used.

And if that threat wasn’t enough, both of the emergency diesel generators are located within the auxiliary building below the two switchgear rooms. After damaging the switchgear, water might have drained lower in the auxiliary building to disable one or both of these backup power sources.

Our Takeaway

The big bad wolf and the three little pigs is a fable.

Adequate protection at nuclear power plants must not be a fable. It must be a fact.

Fukushima was thought to be adequately protected against tsunamis. That fable carried a very steep price tag.

Fort Calhoun began commercial operation in September 1973. It was not discovered until more than four decades later that its protection against internal flooding was a fable, too. Fortunately, transforming that fable info fact carried a lower price tag.

In order to lessen the fable inventory and boost the fact inventory at nuclear power plants, the NRC should conduct a formal case study of this and similar recently identified flood protection fables to determine why its inspection efforts over the past four decades mistakenly took fables for facts. Perhaps, for example, coming back from flood protection inspections with dry feet isn’t the proper measure.

Whatever it takes, the NRC needs to base its safety conclusions on facts rather than fables.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.