The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) just finalized its Phase 3 greenhouse gas regulation as a part of the administration’s plan to decarbonize the transportation sector. The Phase 3 regulation will cut new greenhouse gas emissions from trucks in 2032 by 32 to 62 percent for vocational trucks (e.g., refuse, delivery vans, school and transit buses) and 9 to 40 percent for tractor-trailers, compared to the current 2024 standards. We could also see up to 623,000 electric trucks on the road in this time period, with zero-emission trucks making up over one third of all new truck sales by 2032, according to our analysis…but that number is highly dependent on manufacturer compliance strategy and complementary policies.

The Joint Office of Energy and Transportation recently released a strategy on infrastructure deployment to support a transition to zero-emission trucks, and a number of states are accelerating that transition with sales requirements that ensure increasing share of zero-emission trucks are sold in the state. However, EPA’s final rule fails to capitalize on this momentum, and the path to a zero-emission freight sector remains uncertain. And EPA still hasn’t provided a waiver to California for its Advanced Clean Fleets program, creating uncertainty even in the states that have stepped up in absence of federal action.

To get the transition to zero-emission freight back on track, the Biden administration should develop a comprehensive strategy towards a zero-emission freight sector, including but not limited to eliminating emissions from heavy-duty vehicles. Such a plan should be directly informed by those most harmed to ensure that these rules do not leave behind communities already facing the disproportionate burden of a fossil-fueled freight sector.

EPA’s rule got worse…and better…and worse…since last year’s proposal

Since EPA’s spring proposal last year, there have been a number of changes made. Unfortunately, it is a mix of impacts that are likely, on net, to result in increased diesel truck deployment (and the commensurate harm from their tailpipe emissions) relative to the original proposal.

Across all vehicle classes, EPA has reduced the pace of improvement in the early years of the program. While targets increased in 2032 for some vehicle classes, the vehicles sold under this program will emit more greenhouse gas emissions as a result.

For the heaviest classes of vehicles, the rule’s stringency has been greatly diminished. This will likely set back the electrification of tractor-trailers and create increased uncertainty around the investments needed to electrify our freight corridors.

Increased flexibilities are a critical problem with the rule. EPA extended multipliers for electric trucks by a year (e.g., one battery-electric truck sold counts towards the regulation as 4.5 battery-electric trucks), even though manufacturers are already required to sell those trucks in states that have adopted the Advanced Clean Trucks rule. Worse, EPA now allows for credit trading between vehicle classes, which means these windfall credits will be used to offset what little improvements are required in the earliest years of the program.

One critical piece of the final rule that did not change is the crediting of hydrogen combustion trucks. Hydrogen combustion trucks can be just as harmful as the diesel trucks for which they are promoted as a replacement, but they are treated irrationally as zero-emissions vehicles, which erodes the rule’s ability to drive truly zero-emissions trucks to market.

Overall, the rule’s structure still diminishes its ability to guarantee the deployment of zero-emission trucks.

EPA’s final rule is a performance standard, not an EV mandate

EPA has set a technology-neutral greenhouse gas emissions rule, which means manufacturers have a range of technologies to choose from to reduce those greenhouse gas emissions, the vast majority of which will not result in reductions of the smog-forming and soot pollution inundating communities today. Because EVs are a cost-effective technology for a range of heavy-duty applications, it is likely that manufacturers will deploy them as part of their compliance strategy, but it is the states who are laying that groundwork by providing definitive sales requirements on manufacturers.

Roughly 20 percent of the heavy-duty market (11 states) have adopted the Advanced Clean Truck rule (ACT), which requires an increasing number of zero-emission trucks be sold in those states. California has also adopted the Advanced Clean Fleets rule, which helps create a market for electrification and ensures the entire fleet (not just new vehicles) electrifies—though EPA has been slow to approve a waiver on this rule. Manufacturers get credit under EPA’s rule for electric trucks sold to meet these state standards, so it begs the question: are there going to be more electric trucks deployed in response to EPA’s rule? And if so, where?

Below, I walk through a UCS analysis that tries to dig into this critical question.

This rule is expected to result in additional electric trucks, but not as many as EPA thinks

Because manufacturers can comply with EPA’s rules with any technology that reduces greenhouse gas emissions at the tailpipe, this rule will bolster the deployment of technologies that make diesel vehicles more efficient. While this may be good for cutting greenhouse gas emissions, it doesn’t do anything to reduce the harm from the smog-forming and particulate pollution from those vehicles. And unfortunately, EPA has not factored in the full suite of efficiency technologies in their analysis, which means these heavy-duty rules have plenty of regulatory slack that will ease pressure on manufacturers to deploy the cleanest available technology (electric trucks).

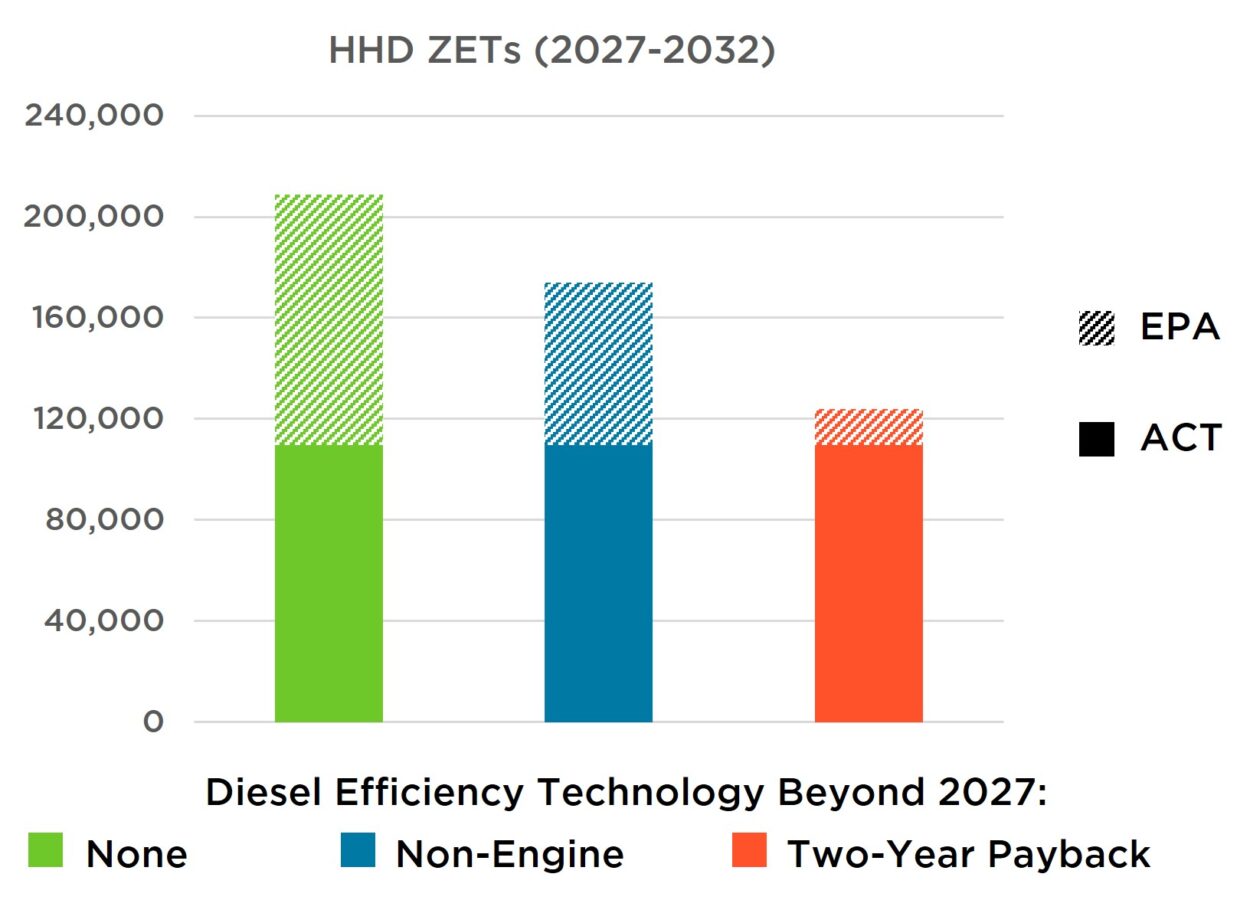

In thinking through how manufacturers will respond to EPA’s final rule, we consider three scenarios: 1) no additional diesel technology deployed beyond what was likely to be deployed under the Phase 2 regulations already on the books; 2) a continually increasing adoption through 2032 of non-engine efficiency technologies that EPA had already identified would be deployed by 2027; and 3) an adoption of diesel vehicle technologies that would pay for themselves within a 2-year timeframe thanks to reduced fuel costs. None of these scenarios represent a significant deployment of the most effective technology to cut fuel use from a diesel vehicle, hybridization, so these scenarios could still underestimate the degree to which diesel-fueled vehicles are used to comply with this regulation.

Even under a best-case scenario, EPA’s rule falls short of the level of zero-emission deployment needed to simultaneously address climate change and the freight pollution overburdening communities around the country. At the same time, the rule is still likely to lead to additional electric truck deployment according to our analysis. But the results vary significantly by vehicle class.

For the light-heavy-duty (LHD) trucks (Class 3-5, which include F-350 work trucks, package delivery vehicles, etc.), EPA’s final rule could result in a similar level of adoption in the rest of the country, if manufacturers primarily use electric trucks to comply with the rule, with an additional 160,000 electric Class 3-5 trucks deployed from 2027-2032 thanks to the added pressure of EPA’s rule. Even if cost-effective diesel efficiency technologies are deployed, EPA’s stringency for LHD trucks is great enough that this would still yield an additional 130,000 electric Class 3-5 trucks. Including ACT, zero-emission trucks could represent around ¼ of Class 3-5 trucks sold in the timeframe of this rule.

Unfortunately, when it comes to the heaviest vehicles on the road, the numbers are not nearly as rosy, because EPA’s rules for Class 6-8 vehicles are far less stringent. This is especially problematic since the largest vehicles have a disproportionate impact on emissions: Class 7-8 vehicles are about half of new heavy-duty vehicle sales but are responsible for 70 percent of all heavy-duty truck fuel use and global warming emissions in the U.S. For reference, Class 6-7 (medium heavy-duty, MHD) vehicles include school buses and large box trucks, while Class 8 (heavy heavy-duty, HHD) include refuse trucks and tractor-trailers.

Weaker stringency translates directly into a weaker push for electrification. ACT is expected to yield over 200,000 zero-emission MHD and HHD trucks in the 2027-2032 timeframe, representing 36 percent of Class 6-8 trucks sold in those states. Optimistically, EPA’s rule could result in nearly 170,000 additional zero-emission MHD and HHD trucks—however, diesel efficiency improvements could cut this number by over 70 percent, to under 50,000. Assuming those trucks are deployed outside of ACT states, this would represent just 2 percent of Class 6-8 sales in non-ACT states over the timeframe of the rule. Worse still, because EPA continues to erroneously credit hydrogen combustion trucks as zero-emission vehicles, that total is likely to be even further eroded.

The weak stringency of EPA’s rule for the heaviest and most polluting vehicles on the road, combined with a technology-neutral approach that doesn’t factor in tailpipe smog-forming and particulate pollution, allows for a disparity in national deployment of zero-emission trucks. The rule risks having communities of haves (in ACT states) and have-nots (in the remainder of the country), precisely the sort of situation a federal rule is supposed to ward against.

Considering how vital electric trucks are to addressing harms from the freight sector, this is unacceptable, even if on net the rule is still likely to result in additional electric trucks beyond what is required under state policies.

Electric trucks offer the clearest path to limiting harm from the freight sector

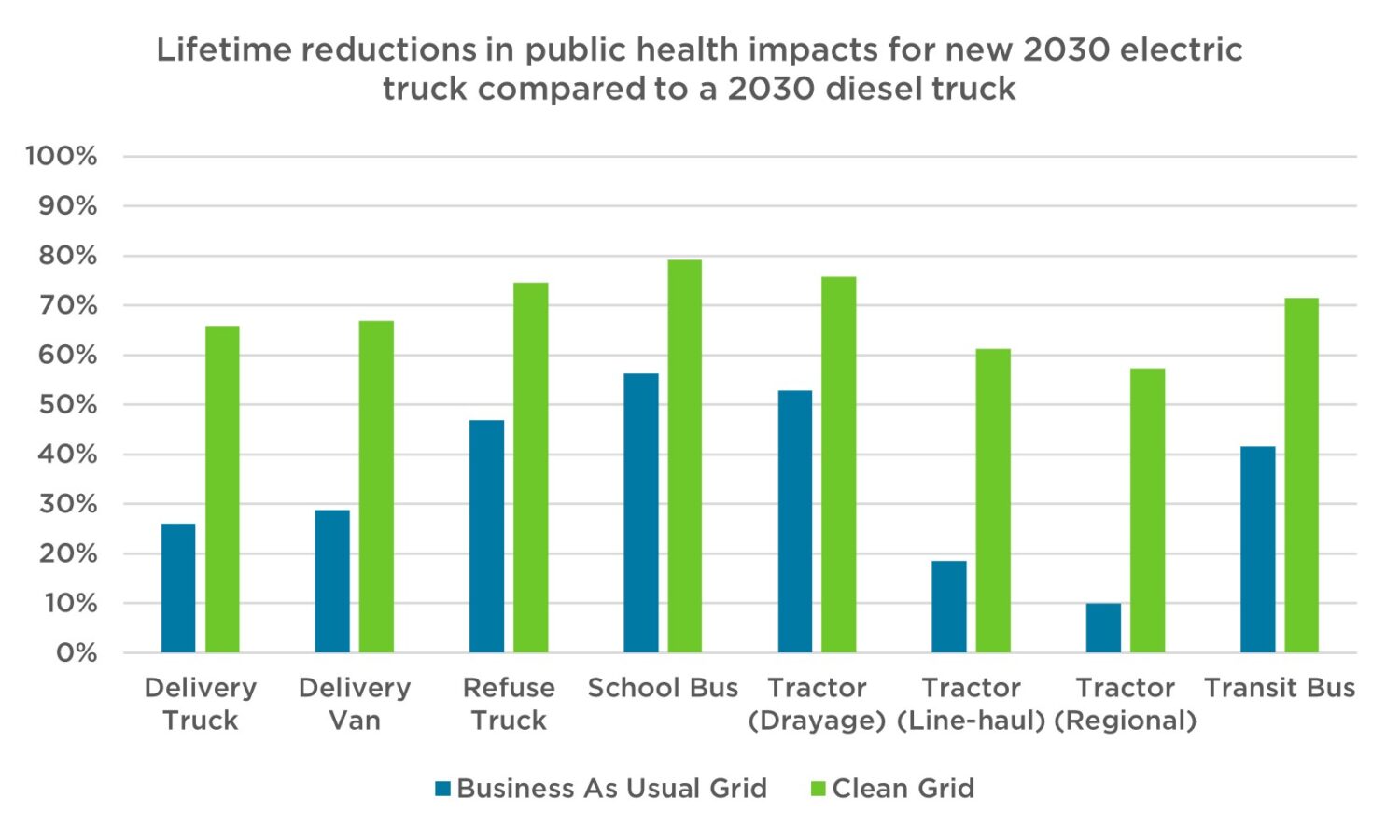

Communities on the ground currently disproportionately burdened by the harms of our freight sector need government intervention to eliminate those harmful emissions, which is why they’ve called for a transition to zero emissions. That path to zero is inclusive not just of the direct tailpipe emissions, but also a just transition for workers and a transition to clean energy to ensure that the transition doesn’t just exchange the health burdens on one community for another.

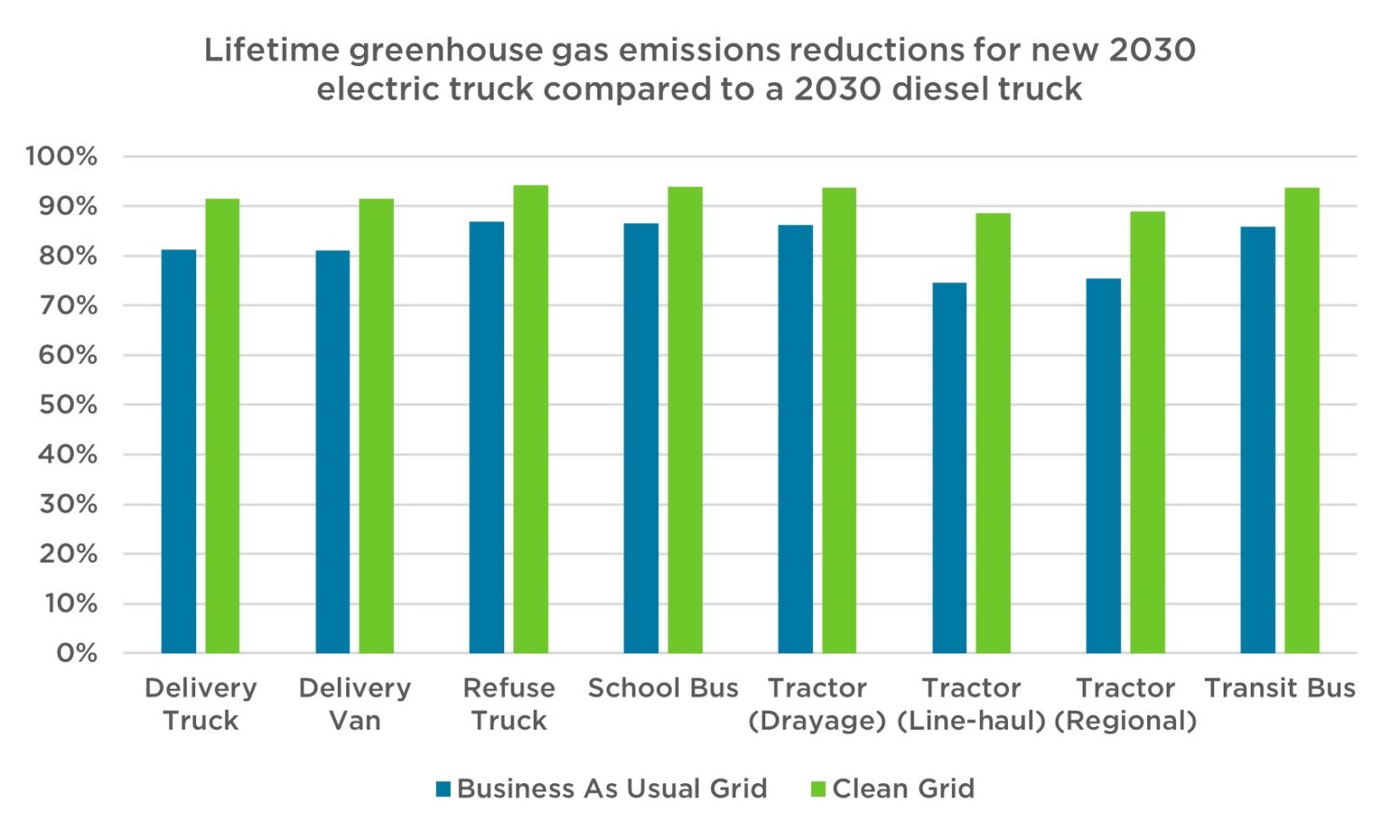

The heavy-duty sector encompasses a wide range of truck types and operating conditions, but no matter the type of vehicle, electric trucks represent a tremendous opportunity to cut greenhouse gases, which is why they’re highlighted by EPA in its rule.

Of course, for the communities already overburdened by freight pollution, the motivation for zero-emission freight is remedying the more direct public harm caused by thousands of trucks driving past. This is why when EPA was considering changes to its smog-forming and particulate pollution standards for heavy-duty vehicles we pushed for EPA to use that opportunity to drive the sector to zero tailpipe emissions and why it’s a missed opportunity that this rule doesn’t reflect a multipollutant strategy to drive ALL emissions from new trucks to zero.

We need a cohesive, comprehensive, and coordinated zero-emission freight strategy built on EJ community input

While this final rule provides some additional push to drive the freight sector to zero emissions, this rule is not happening in a vacuum. Because the number of electric trucks deployed under EPA’s rule are entirely dependent upon manufacturer strategy, the best thing the administration can do now is to support the deployment of electric trucks through complementary policies to help ensure that the rule is complied with in a way that will maximize the public health benefits.

A commitment to a 100 percent zero-emission freight sector would not only improve environmental and public health but bolster economic growth by advancing green technologies and job creation. Importantly, this comprehensive strategy when put into action could not only ensure coordination around a national charging system for freight corridors that will target a zero-emission truck fleet, but it would also help move the conversation beyond trucks to other sources of emissions harming communities around ports, warehouses, and rail/multimodal facilities, including locomotives, freight equipment, and ships.

Today’s EPA rule is not the single visionary policy needed to achieve a just path to zero, but it could be a positive step toward meaningful action. In order to drive the change needed for communities burdened by the harms of our freight sector today, and to align with the administration’s stated vision that “environmental justice is a whole-of-government commitment that requires early, meaningful, and sustained partnership with communities and dedicated leadership in Federal agencies,” the Biden administration should work with communities to develop a clear and comprehensive path to zero-emission freight.