The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has acknowledged its extensive history of discrimination directed at Black farmers and other marginalized groups. This discrimination has manifested itself in denying farmers access to low-interest loans, subsidy payments, grant programs, and other forms of assistance. Black farmers have been subject to other systematic barriers such as longer processing times for operation loan applications and higher loan default rates, and they have been denied access to information and resources. Many experienced tremendous economic loss and lost their land as a result. This discrimination has been deeply rooted in the history of the country’s agricultural and financial institutions, from the post-Civil War era and continuing throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Let’s backtrack to the post-Civil War era

Enslaved people had limited access to land. Following the formation of the USDA in 1862 and the abolishment of slavery in 1865, many formerly enslaved African Americans pursued independent farming. This was a losing battle for most of them. Not only were they met with pure hostility, outright violence, and exclusion, but the US government also made unfulfilled promises to provide land to freed men. Such promises included “40 acres and a mule,” the first unsuccessful systematic attempt at providing reparations.

By 1866, the Southern Homestead Act was passed to help formerly enslaved individuals acquire their own land, but it failed and had to be repealed because of poor land, poor agricultural resources, and hostility from White people. The Southern Homestead Act was enacted to redistribute 46 million acres of land to formerly enslaved people. However, most of the land offered was of poor quality and was not suitable for farming. By the time the act was repealed in 1876, only 3 million acres had been distributed, with most of it going to White people. Approximately 6,500 free Black people filed claims, but only 1,000 of them received property certificates. The failure of this act likely played a role in paving the way for sharecropping and tenant farming.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, another opportunity for land ownership was presented through sharecropping and tenant farming. Sharecropping was a system in which the landowner permitted tenants to use their property for farming in exchange for housing and a share of farmers’ profits. This was yet another exploitative system that only benefited wealthy White farmers. High interest rates, erratic harvests, and deceptive landlords kept Black farmers trapped in cycles of debt and poverty, as they were forced to carry debt over to the following year.

Despite these structural and systemic barriers, Black land ownership gradually increased and reached an all-time high national average of 14% and a total of 925,000 farms by 1910. The post-Civil War decades saw formerly enslaved people and their offspring accumulating as much as 19 million acres of land—about the size of South Carolina. This massive land accumulation was aided by Black institutions that provided access to small loans and other resources.

How federal inaction chipped away at Black progress

As the 20th century progressed, Black farmers continued to encounter systemic barriers and legal discrimination that limited their ability to own land and be successful farmers. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 incentivized the production of certain crops by providing farmers with subsidies. The USDA perpetuated racism by allowing White landowners to retain these subsidies instead of transferring them to Black farmers who sharecropped on their property.

In 1937, USDA farm loan programs were introduced through the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act and administered by the Farm Security Administration. These loans sought to help farm tenants, farm laborers, and sharecroppers purchase land and other necessary farming resources. However, local county committees reviewed the applications and made the lending decisions. These were generally affluent White landowners who were likely biased in favor of the status quo and had the power to exclude Black farmers from federal assistance.

Preference was given to prospective borrowers who were married and with dependents, already owned livestock or farm equipment, and could afford to make a down payment on the loan. Whether as a result of conscious or unconscious bias, the program disproportionately denied loans to Black farmers. Discrimination included outright denial of loans, smaller loan amounts, delaying the loan application processing times for Black farmers, and worse loan terms than their White counterparts. These discriminatory lending practices ultimately made it difficult for Black farmers to secure sufficient funding to purchase land and farm supplies.

It is well documented how credit access or lack thereof can limit liquidity, and in turn negatively impact farm productivity, profitability, and farm income. This is because without cash at the beginning of the growing season, farmers may be forced to use lower-quality inputs (such as equipment and fertilizer) or lower amounts, which consequently reduces output and farm productivity. Consequently, Black farmers in the early 20th century lagged behind their White counterparts in agricultural mechanization. Moreover, many of them accumulated debt, faced foreclosures, and subsequently lost their land.

Between 1910 and 1997, Black farmers lost approximately 90 percent of their 19 million acres of land, decimating the number of Black-owned farms by more than 95 percent: from 925,000 in 1920 to a meagre 45,000 by 1975. The compounded value of Black land loss in the 20th century has been estimated to be roughly $326 billion. This Black land loss was a consequence of a lack of federal oversight to end the prejudice by the USDA and the violence in the South that used lynching and terrorist threats to drive Black people out of their homes and farms, among other factors.

Taking on the USDA

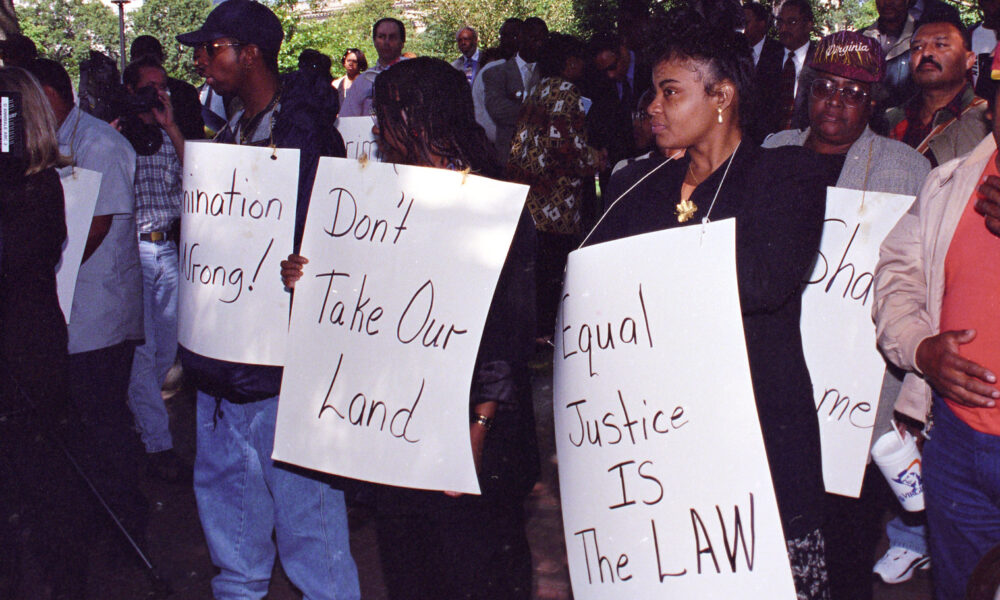

Starting in the 1980s, Black farmers began to organize and file complaints against the USDA for its discriminatory practices. This led the USDA to commission several independent consultants to investigate these claims. Several reports issued by the House Committee on Government Operations (1990), Westover Consultants (1993), consultant D.J. Miller (1996), and others revealed some existing civil rights violations and discriminatory practices within the USDA.

The 1990 farm bill introduced the USDA’s 2501 program to assist “socially disadvantaged” farmers, ranchers, and foresters who have historically been excluded in USDA programs and services, and to ensure that underserved farmers could equitably participate in USDA programs. By 1992, Congress had mandated the Farm Service Agency to designate part of its appropriated funds for loans to minority farmers and ranchers.

Decades of discrimination against Black farmers culminated in organizing that led to the filing of the Pigford v. Glickman class-action lawsuit in 1997. By this time, the USDA had already acknowledged the systemic racism that existed within its programs. The farmers in the suit alleged that the agency had discriminated against them based on race when they applied for farm loans, and that it ignored and failed to properly respond to their complaints between 1983 and 1997. The US District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in favor of the claimants and the USDA was ordered to make settlements of more than $2 billion, making it one of the largest civil rights settlements in US history.

The settlements were released in two phases: Pigford I and Pigford II. The first awards were settled in 1999, with only 15,645 (69%) of the 22,721 eligible class members receiving payouts. Pigford I was settled in two primary types of compensation: Track A, which awarded a flat amount of $50,000 and tax relief and forgiveness of any outstanding USDA loans, only if the farmers could demonstrate their loan was denied, delayed, or decreased based on their race; and Track B, which allowed farmers to receive larger amounts as a percentage of the total cost of discrimination. This award required the claimants to provide extensive evidence that the USDA discrimination cost them more than $50,000. Because of the complexity and the burden of proof, most farmers opted for Track A and only 115 received settlements in Track B. The Pigford II settlement was reached in 2010 for those farmers who had missed the filing deadline, with a total compensation of $1.25 billion made to eligible Black farmers.

The USDA continues to address discrimination

In recent years, there has been a renewed push to tackle the long-standing discrimination that Black farmers have faced and continue to face. New initiatives have been launched to offer technical support and ensure equitable treatment for all farmers in USDA programs, including an Equity Commission and $2.2 billion for financial assistance for farmers who experienced discrimination by the USDA farm lending programs made available through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) .

In 2021, the USDA established its Equity Commission, which was tasked with analyzing and addressing historical discrimination and promoting equity within the department’s programs. In its final report, the commission made 66 recommendations including advancing department-wide equity, supporting minority farmers and ranchers, and investing in rural development operations using a top-down approach with rural and minority stakeholders, among others.

Recently in July 2024, the USDA announced it had issued payments amounting to $2.2 billion to eligible farmers. Although much of the advocacy surrounding this program began with Black farmers, it is race-neutral, following a series of lawsuits to halt any payments directed solely at farmers of color. The payments ranging between $10,000 and $500,000 were awarded to 23,000 individuals, and 20,000 other individuals received between $3,500 and $6,000. US Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack alluded that the financial assistance was by no means compensation for the long-standing pain and loss suffered by Black farmers but rather just an acknowledgement of discrimination.

The history of discrimination against Black farmers by the USDA highlights the deep-rooted systemic issues that have contributed to the economic marginalization of Black farmers. While there have been steps towards justice and equity, there is still a long road to be traveled to ensure that Black farmers are fairly compensated for the losses they encountered because of discrimination in the USDA. Black land loss is a civil rights issue, and addressing it requires a combination of policies that target past injustices, provide financial and technical assistance, and create sustainable opportunities for growth.

Some policy recommendations include heirs’ property reform. Heirs’ property refers to the loss of land due to unclear titles and lack of access to legal resources, and it is a leading cause of Black land loss. Moreover, without clear titles it is hard to secure loans. The USDA should, in consultation with those affected by heirs’ property, create programs that will support them and meet them at their points of need.

Developing land acquisition and preservation programs could be another means of curbing Black land loss. Land acquisition and land trust programs could be established to help Black farmers buy back lost land or acquire new land. The Justice for Black Farmers Act could play a significant role in improving access to legal assistance, affordable credit, and loans, as well as funding interdisciplinary research and extension at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and 1890 land grant institutions.

The upcoming farm bill is another opportunity to address past injustices experienced by Black farmers and build a just and equitable food and farm system. The farm bill could ensure that there are investments in a dedicated source of multi-year funding for technical service providers supporting underserved producers, and that USDA land-related programs track and publicly report demographics data on program participants.

[NOTE: This post was updated to correct the year in which the Southern Homestead Act was repealed.]