Ever since I can remember, when I have come to the “What is your race and/or ethnicity?” question on a government form or survey, I’ve paused. As an Iranian American, I always wondered why there wasn’t a “Middle Eastern” option, as I have never felt that the provided categories quite captured my identity. Sometimes, there would also be a note: “White, including Middle Eastern origin.” This directive left me confused as it conflicted with my life experience. How can I be “White” when the people in my community, especially visibly Muslim populations, have been subject to hate crimes specifically because we are not White? How can that be true when terrorist jokes were thrown around callously after 9/11, or when my Iranian-born family have been detained in airports for no other discernable reason than their ethnic heritage? To me, it felt like choosing “White” erased the context of my experience as a Middle Eastern American. Left without a clear alternative, I’d hesitantly select “Other” or “Prefer not to say.”

Fortunately, this will no longer be a question I grapple with after the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued new standards updating how federal agencies will collect and report data on race and ethnicity. Earlier this year, OMB’s new Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, among other things, added a new “Middle Eastern or North African” (MENA) category that will appear on federal forms and surveys, like the US Census.

These revisions are the result of a nearly two-year process led by the Interagency Technical Working Group of Federal Government career staff who use race and ethnicity data. The updated standards were developed based on input from nearly 100 listening sessions and more than 20,000 comments submitted by members of the public and research and advocacy organizations like UCS.

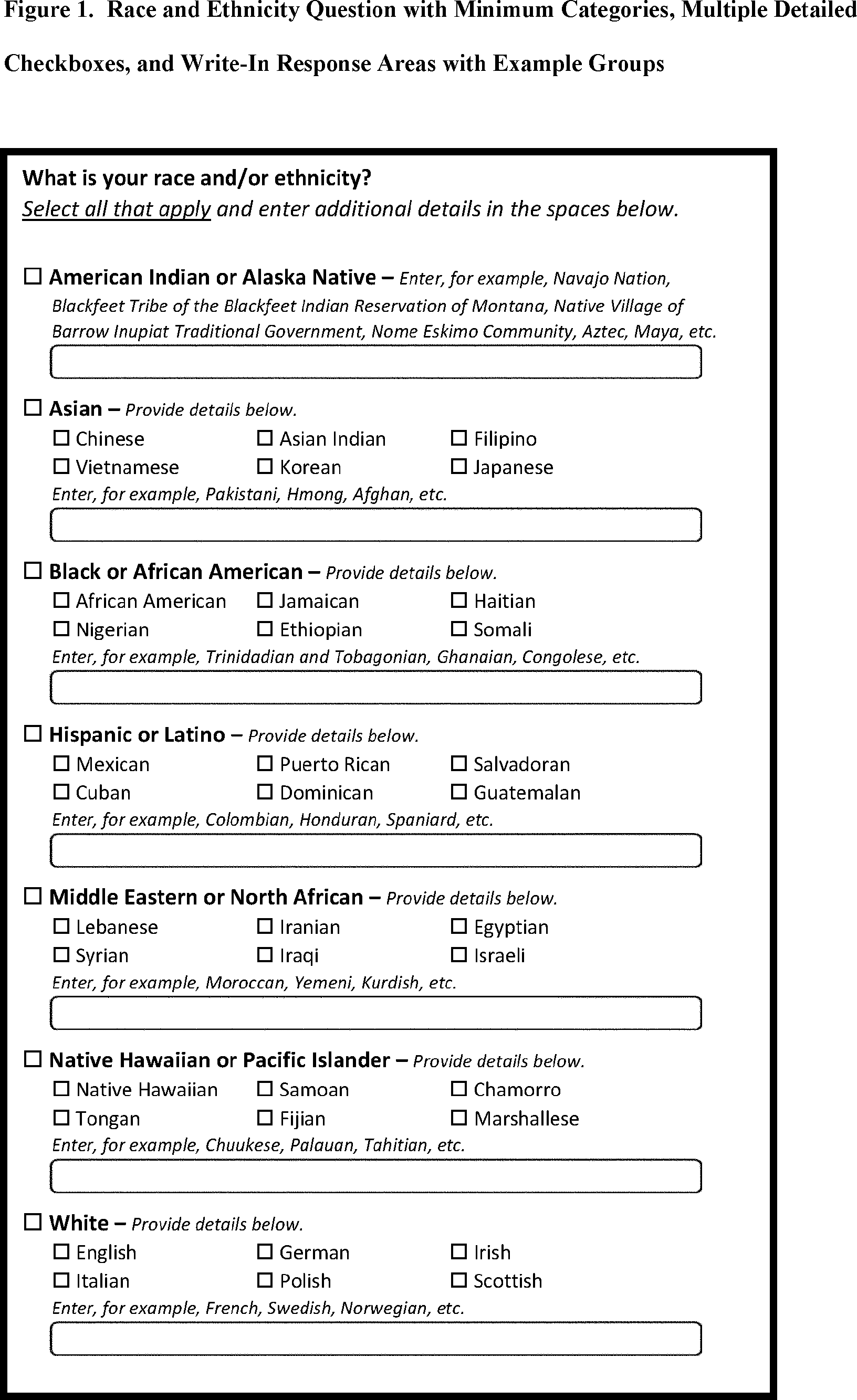

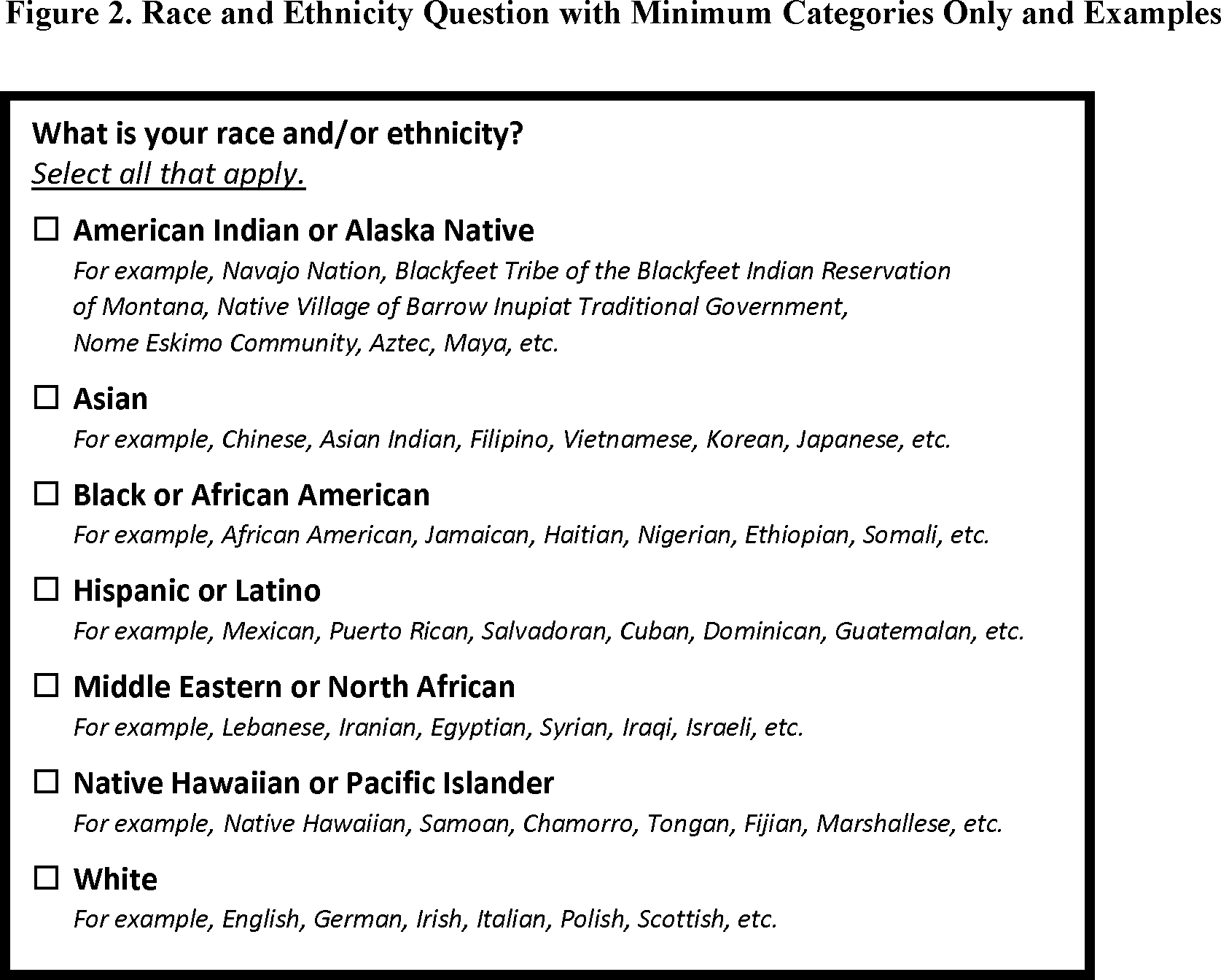

This is the first time these standards have been updated since 1997 and will change what people like you and me will see when we, for example, answer race and ethnicity questions on student loan applications or when filing taxes. Broadly, the changes include:

- Adding a new required category “Middle Eastern or North African” to survey questions related to race and ethnicity

- Using one combined question for race and ethnicity and allowing respondents to select multiple race and ethnicity categories. This means that there will no longer be a separate question that asks, “Are you Hispanic or Latino?”

- Adding detailed categories under each race and/or ethnicity category

- Eliminating the use of dehumanizing language in the terminology and definitions of racial and ethnic groups

Based on these changes, the question about race and/or ethnicity on government forms and surveys may look like this:

While these changes may seem minor, they will yield sweeping shifts in policymaking, resource allocation, and scientific research. Data collected by the government is widely used to inform where federal grants and programs are directed, and by federal scientists and other researchers to understand conditions and disparities faced by specific population groups.

Middle Eastern and North Africans will no longer be invisible in federal surveys

OMB’s decision to add a category for MENA populations was based on input from thousands of public comments and in the listening sessions, but also based on empirical evidence. Research shows that MENA populations largely do not perceive themselves to be White. As stated by OMB’s working group, “many in the MENA community do not share the same lived experience as White people with European ancestry, do not identify as White, and are not perceived as White by others.”

When people like me select options like Other or Prefer not to say, etc., our existence is effectively rendered invisible in the eyes of the federal government. As a result, MENA populations in the US are generally poorly understood, particularly with respect to public health disparities. Evidence suggests that public health burdens in MENA populations are obscured when they are lumped into the “White” category. Studies comparing Arab American and White populations in California and Michigan found that Arab Americans were more likely to not be covered by health insurance, not own a home, live below the federal poverty level, and bear a higher burden of certain cardiovascular and respiratory conditions than White populations. Additionally, a study of COVID-19 disparities in Toronto, Canada found that Arab, Middle Eastern, and West Asian populations had a three- to five-time greater COVID-19 infection and hospitalization rate compared to White populations.

Adding a category for MENA populations will provide government agencies and researchers with data that enables development of programs designed to support and eliminate disparities in these communities.

Multiracial populations will be better represented in federal surveys

In addition to adding a new MENA category, the standards will now use a single, combined question for race and/or ethnicity. This means that there will no longer be a separate question asking, “Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin?” Respondents will also be able to select multiple categories in response to the single race and ethnicity question.

This decision is backed by decades of research and polling showing that people of Hispanic or Latino origin largely do not identify with the race categories provided in the US Census. Indeed, nearly 44 percent of people who identified as people of Hispanic or Latino origin in the 2020 Census did not respond to the separate question about race, or selected “Some Other Race.” According to a Pew Research Center survey, unlike White and Black identifying respondents, less than half of respondents who identified as Hispanic or Latino felt the 2020 census questions reflected their identity “very well.”

According to research by the US Census Bureau, a single combined question will result in fewer “Other” responses, invalid responses, and non-responses; and increase responses of “Hispanic or Latino.” Allowing selection of multiple race and/or ethnicity categories will also enhance representation of multiracial populations, such as Afro-Latine people, who comprise roughly 12 percent of the adult Latine population.

Survey respondents may also have the option of writing in their specific ethnic origin, which may provide additional data on specific population groups. Collecting additional disaggregated data will allow for a more useful and nuanced understanding of the disparate lived realities of different populations—for example, among groups categorized as “Asian,” a category which covers about 20 million people and more than 20 ethnicities.

Standards can enable more equitable distribution of resources

Ultimately, race and ethnicity are complex concepts with varied understanding among the US population. Even in public health research, these concepts are not consistently measured or defined. But these new standards reflect decades of research and countless public comments, representing a step forward in undoing a troubling legacy of collecting racial data for the purpose of segregation and discrimination. Importantly, the updated standards also eliminate the use of racist and dehumanizing language previously used to define racial and ethnic groups. The hope is that these new standards will yield a clearer picture of the diverse identities among the US population and enable more equitable distribution of social services, such as targeted health programs that aim to eliminate disparities.

What remains to be seen is whether the incoming Trump administration will thwart implementation of these new standards based on a mandate in the right-wing agenda Project 2025, which recommends that the new administration review the new standards due to unfounded and politically divisive concerns that that these changes are “skewed to bolster progressive political agendas.” Do not be mistaken: these standards were based on tens of thousands of public comments, evidence-based research, and years of advocacy.

Looking ahead, the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey as well as the 2030 US Census should incorporate these changes. If you didn’t have a chance to weigh in on these standards, you can also provide feedback on how federal agencies should implement them on various government forms here.