UPDATE 9/27/17: View our recently-released visualization of the US nuclear arsenal for a breakdown of every bomb and warhead in the US arsenal.

The United States last week finished removing the last MIRV (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle) from its Minuteman 3 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs); these missiles will now each carry a single warhead. The move was the fulfillment of a promise the Obama administration made in its 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, which stated that it would “enhance the stability of the nuclear balance by reducing the incentives for either side to strike first.”

It is also another step toward compliance with the New START treaty, under the terms of which the United States and Russia will each reduce the number of their deployed strategic warheads to 1,550 by 2018 (Russia is already below this number, the U.S. is still working on it).

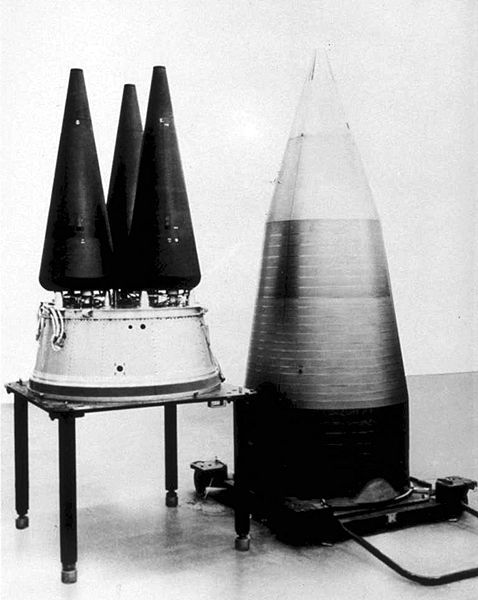

MIRVs were a cold war invention made possible by advances in nuclear weapons design that allowed development of warheads small enough that several could fit on one missile. Missiles are expensive, and MIRVs were a way to maximize the damage that a single missile could cause. They were quickly adopted by the United States and Soviet Union for both ICBMs and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs).

The United States first tested MIRVs in 1968, and first deployed them in 1970 on the Minuteman 3, which can carry up to 3 warheads. The U.S. Peacekeeper missile, the last of which was decommissioned in 2005, could carry up to 10 warheads. U.S. SLBMs still carry MIRVs, although the number of warheads loaded onto one missile is being reduced. Russia is more dependent on MIRVs than the United States, using them on both ICBMs and SLBMs, and a new version of the Russian SS-27 ICBM is reportedly able to carry up to four warheads.

One major problem with MIRVed ICBMs is that just one incoming nuclear warhead could destroy all the warheads on the MIRVed ICBM. This creates a “use them or lose them” scenario—an incentive to strike first in a time of crisis. Otherwise, a first strike attack that destroyed a country’s MIRVed missiles would disproportionately damage that country’s ability to retaliate. (Since SLBMs are generally considered to be invulnerable to attack, they do not create the same concern.)

Completing the transition to single warheads for U.S. ICBMs is a milestone worth acknowledging, but there is still more to be done to bring the U.S. nuclear posture into alignment with the current international security situation. The United States still has about 450 de-MIRVed Minuteman 3 ICBMs, most of which are kept on high alert, ready to launch in minutes. Like MIRVs, this alert status is a relic of a different time, designed to respond to a different threat. And—also like MIRVs—it is dangerous. Maintaining U.S. weapons on high alert increases the chance that one or more of these missiles will be launched by accident, without authorization, or in response to a false warning of attack. It also encourages Russia to keep its missiles on high alert.

De-MIRVing ICBMs is a step in the right direction, but there is more that the United States must do to reduce the risks of nuclear use. Taking these missiles off high alert would be a significant next step toward this goal.