Some say the only things you can count on are death and taxes, but in California there’s something else: drought. No one knows how long the current drought will last or when the next drought will be, but we can be sure that droughts will continue to cycle through in California. Unfortunately, many of our water management systems haven’t been built with this basic fact in mind and aren’t being operated to deal with longer or more severe droughts in the future.

UCS climate scientist Juliet Christian-Smith is the lead author of a new article in Sustainability Science (subscription only) describing how the actions that have made California relatively resilient to short-term drought are setting us up for trouble in the long run and can be considered “maladaptation.” The article finds that California’s current strategies for dealing with drought are less successful than previously thought when short- and long-term impacts are evaluated together. This finding is particularly relevant given projections of more frequent and severe water shortages in the future due to climate change.

The analysis reveals that while California’s agricultural and energy sectors displayed remarkable resiliency to the 2007-2009 drought, sustaining high production levels, they did so by relying on a series of coping strategies that increased vulnerability to longer or more severe droughts.

For example, California is currently living off credit by overpumping groundwater from its aquifers. Groundwater is one of the primary ways that the agricultural sector insulates itself from drought impacts, yet as groundwater levels continue to drop, groundwater pumping is becoming less economical (more expensive to pump water up from deeper depths or to drill deeper wells) and ultimately unsustainable as we are pumping out more water than is available to refill those aquifers in many locations.

In addition, California’s hydropower was roughly halved during the 2007-2009 drought. This lost hydropower was largely replaced with the purchase and combustion of additional natural gas. Ratepayers spent $1.7 billion extra to purchase natural gas over the three-year drought period; the combustion of this extra natural gas led to emissions of an additional 13 million tons of carbon dioxide (about a 10 percent increase in emissions from California power plants).

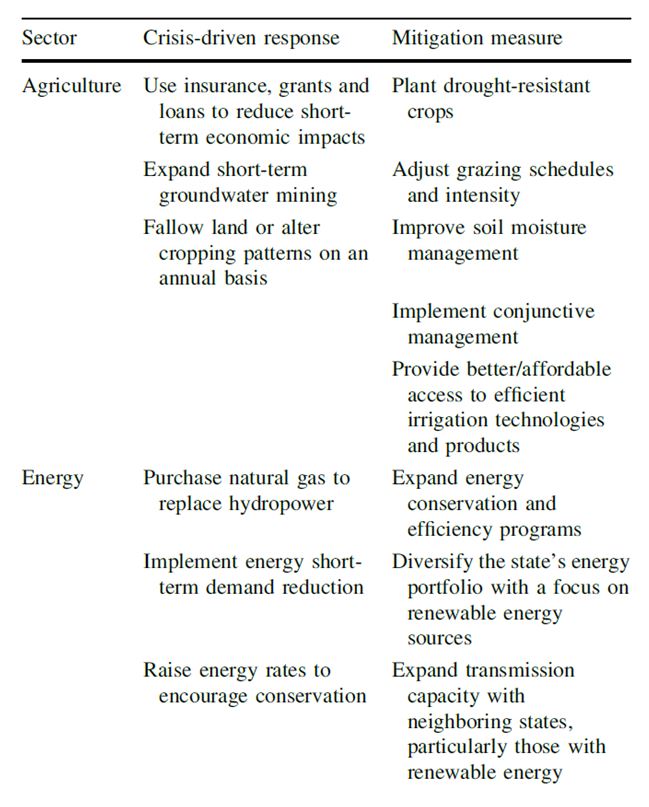

Overall, California continues to respond to drought through a series of shortsighted, crisis-driven responses, rather than pursuing more robust mitigation measures (see the following Table, reprinted from the article). The article provides a series of recommendations for the development and enactment of long-term mitigation measures that are anticipatory and focus on comprehensive risk reduction. It is past time to learn how to live with the inevitable: death, taxes and, for Californians, drought.