During a California State Assembly informational hearing earlier this year, there seemed to be consensus that California’s 19th century water rights system is not well suited to the social context and climate of the 21st century. Change is necessary and may be coming.

This outdated water rights system is based on historic and continued disenfranchisement and dispossession. It has persisted for more than a century, despite known inequities and increasing inadequacies in the face of climate change. It persists because powerful actors benefit from the current system and its haphazard enforcement, and they vehemently resist any proposed changes.

They can be convincing. After all, water rights seem overwhelming and complex. I’ve studied water policy in California for more than a decade, and water rights was something I had always left for the lawyers—people like Doug Obegi, senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, who explains, “…we’ve made water policy more complicated than it really is, and that has made it harder for the public to engage on these issues, because it gets cloaked in this kind of mythical sense that it’s too complicated.”

Indeed, “it’s complicated” is not the end of this story; it’s only the beginning.

Note: As a California transplant and a white person of settler-origin, it’s important to reflect on whose narratives have dominated the discussion of water rights. The history of the water rights system is one of state-sponsored violence against Native Americans and the structural racism encoded into our legal system. It would be irresponsible to not acknowledge that. I draw heavily from several episodes of the podcast, West Coast Water Justice, which is produced by the Indigenous-led non-profit Save California Salmon. In this post, I’m using “Native American” or “Indigenous” throughout based on the Union of Concerned Scientists’ style guide, but these terms are imperfect and not always preferred. Where possible I use an individual’s specific Indigenous community name. Trigger warning below for settler violence and genocide.

A primer on California’s water rights system and its settler roots

To understand why today’s water rights are so convoluted and steeped in bigotry, we must go back in time to more than a century ago.

First, the water rights system is designed to distribute surface water, or the water that flows through the state’s 189,454 miles of rivers, countless streams and creeks. Surface water rights determine who, where and for what purpose surface water is used. California’s current water rights system is tied to the conquest of California by the United States from Mexico (1848) and the enormous influx of settlers during the Gold Rush (1848-1855). A more thorough history would include the settling and colonization of California by the Spanish (1500s) and Mexican (early 1800s) governments, but for brevity, I focus here on the intentional and duplicitous actions of the California state government (established in 1850) and its co-conspirator: the United States federal government.

California has both types of water rights systems used in the United States. Riparian rights were inherited and adapted from British common law and are primarily used in rainy eastern states. A riparian area is the place where land and water meet; riparian water rights are linked to owning the land that borders water. Riparian landowners may only use the water on the land that is adjacent to the water source.

White settlers of the west invented a second system called appropriative rights during the 19th century. Appropriative rights do not require the holder to own land adjoining a water source, the way riparian rights do. They allow the holder to divert water from one point, and use (or “appropriate”) it at a different point if beneficially used. Up until 1914, appropriative water rights could be claimed in California by simply posting notice of a claim–known as “staking”–and then putting water to use. (Literally, this often meant just hammering a sign onto a post by the river.)

An appropriative right originates when the holder can physically control water for beneficial use. Beneficial use was originally defined as agricultural, industrial, or household use, and more recently has been modified to include recreation and ecosystems. The doctrine of prior appropriation means that an appropriative right is based on a ‘first in time, first in right’ priority system. Unlike riparian rights, which stand whether or not water is used, appropriative rights holders must show continual water use. An appropriative right can be lost after five years of non-use if it is not contracted out (transferred) to another entity.

The 1886 California Supreme Court ruling Lux v. Haggin formally blended the two systems with riparian rights treated as (mostly) more senior than appropriative rights, although not in all cases. In practice, this means “water generally went to those with the most creative lawyers and engineers” as journalist Mark Arax writes in The King of California.

Both of these systems were designed in concert with federal and state policies to benefit white settlers and strengthen the state and federal governments’ hold on newly claimed but unceded territories. The 1862 Homestead Act, for example, allowed adult citizen heads of households to gain ownership of a piece of land by occupying and “improving” it for a period of five years. Of course, Native Americans were not eligible for US citizenship until 60 years later, in 1924. By incentivizing the occupation of land, ownership by force, and exploitation of natural resources, the state and federal governments promoted the violent dispossession and genocide of Native Americans from the land.

The system was designed to keep water out of Indigenous hands

The system’s origination in dispossessing Native Californians from the land, and reallocation to the settler colonizers is an historic and ongoing violence. The state considers the pre-1914 appropriative claims as among the most senior of water rights. From the 1850s through today, those rights have enabled settlers to mine and farm further and further inland, away from sources of water. The time-based nature of appropriative rights leads to a system of prioritization where the oldest and most senior rights are held almost exclusively by white men.

Native Americans in California, while living there since time immemorial (quite literally ‘first in time’), have been systematically dispossessed of their land and water. One of the first pieces of legislation passed by the inaugural California legislature was an Act for the Government and Protection of Indians (1850). The Act facilitated –among other heinous things– land dispossession, indentured servitude of minors and adults to white settlers, and no legal rights for Native Americans to things like due process. The subsequent decades, marked by the California Indian Wars (1850-1880) were a state-sponsored genocidal campaign to further terrorize and dispossess tribes, including paying bounties for murdered Native Americans.

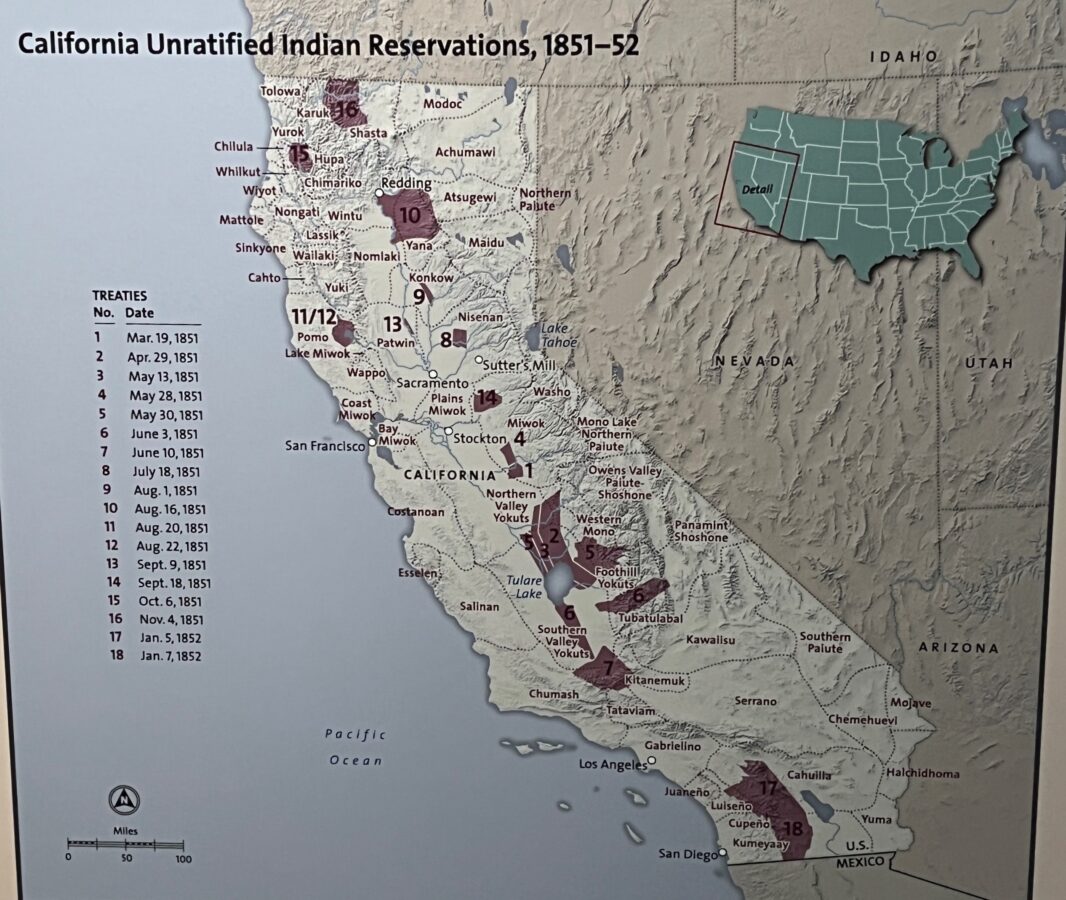

Between 1851 and 1852, 18 “peace and friendship” treaties were “negotiated” by the federal government with Native Americans in California. These treaties traded the federal government’s –often undesirable– proposed reservation lands for any claim Native Americans might hold to their land in California.

Why would any Indigenous community sign onto such a bad deal? UC Davis Professor Beth-Rose Middleton Manning explains here that tribes were under a near-constant threat of violence, including in the treaty “negotiation” process. Chief Caleen Sisk of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe describes, for example, how her relatives narrowly escaped a treaty signing meeting turned mass murder by jumping into a river. The Indigenous treaty signers understood that they would at least secure a place to live away from settler violence, even if on smaller, less desirable, pieces of land far from their ancestral homes.

However, the state of California actually lobbied the federal government against ratifying these 18 treaties because they thought the tribes were going to get too much land, especially in the Central Valley. Thus, the treaties were never ratified by the US Senate, land was never legally taken from tribes, yet they remained landless in practice. The treaties’ existence was then held in secret until 1905. Only after decades of legal battles did any of the tribes get any kind of compensation for their unceded territory.

Inequities resulting from this era, including from the unratified “secret” treaties, is that the state does not adequately recognize Native American water rights. Countless individuals and businesses have since gained titles to stolen land and secured water rights without recognizing Indigenous sovereignty. For anyone that wants to learn more, California Indian Legal Services has a helpful three-part overview of tribal water rights in California and Save our Salmon developed an “Advocacy and Water Protection in Native California” curriculum that covers much more than water rights.

Native American scholars like Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy (Hupa, Yurok, Karuk), Dr. Brittani Orona (Hupa, Hoopa Valley Tribe), and Dr. Andrew Curley (Diné) have illustrated how Indigenous people are in “complicated and fundamentally entangled political landscapes” by having to assert sovereignty and seek recognition and water rights within the United States’ settler-colonial legal system.

California formally apologized in 2019 for genocide, but the question of making water rights right was not considered then.

The system continues to privilege white settlers

How much water gets diverted from rivers and who gets to use it is dependent on the State Water Resources Control Board. I will call them “the Board” from here on out. They implement and enforce water rights prioritizations.

The 1913 Water Commission Act established a Water Commission with the authority to permit new appropriative rights as of 1914, the Act’s effective date. This essentially created two classes of appropriative water rights holders: 1) pre-1914 (“seniors”) and 2) post-1914 (“juniors”). The two classes face different rules, different levels of oversight, and most importantly different levels of curtailments (or restrictions on water use) during periods of shortage; the most junior right holders are curtailed first in California. If you follow water issues in this state, you may have read about severe curtailments in recent years.

When there is not enough water to go around, the Board has to implement and enforce the water rights priority system. Curtailments are one of these tools. The Board can only curtail water rights holders after a Governor-declared drought emergency or a “critically dry” year (which only happens after there have been two previous dry years). Courts have ruled that the Board cannot curtail senior water rights solely on a finding that there’s not enough water in the system to meet those rights. They can, however, once they have enacted an emergency regulation that sets a minimum flow in the river.

In other words, declaring a drought emergency like Governor Gavin Newsom did in 2021, while a prerequisite, is not always enough to stop senior rights holders (again, held almost exclusively by white men) from continuing to withdraw water even during extremely dry years. A new report last month summarizes how “limited and cumbersome options for enforcing curtailments allow bad actors to cause irreparable harm while risking only modest financial repercussions”.

Another challenge: the Water Commission did not have the authority to decide on water rights prior to 1914, and The Board, its current incarnate, remains without power to adequately regulate pre-1914 senior water rights. The most senior rights holders do not have to get a permit or license from the state of California to withdraw water. While many of their water diversions have been vetted by filed “claims” with the court, not all have been verified by the Board. The Board generally knows who the pre-1914 senior water rights holders are, but most of the essential water rights claims documentation are inaccessible paper records. “So we simply don’t know who can legally use water at a given time and place,” as this LA Times opinion writer cautions. Furthermore, the Board relies most heavily on self-reported annual information by the water right holders themselves to inform their calculations about how much water is available for use.

Still with me? This was a lot to process and probably why water rights is a thorny mess that even experts and water enthusiasts don’t engage in. For me, knowing the history is even more motivation to improve the water rights system.

California has made some of its biggest water policy changes during times of crises. What changes are possible during a year with record breaking rainfall and an impending “big melt“?

California’s antiquated water rights system is not ready for climate change

A 2015 study estimated that post-1914 appropriative water right allocations were approximately five times the state’s average annual runoff. In the state’s major basins the allocations account for up to 1000% of natural surface water supplies. This means that what water rights holders can divert (on paper) in California is far, far more than how much water actually exists.

Given increased whiplash extremes from drought to flood, only rarely does any rights holder get 100% of their allocation. This over-allocation combined with the climate-driven uncertainty of water availability, is no match for “a state [water rights] regulatory system dramatically unprepared to address chronic water shortages and an ecosystem collapse,” according to a Sacramento Bee investigation.

In theory, the water rights prioritization system is intended to prevent conflicts by laying out a clear order of priority for whose water use gets cut first in times of scarcity. In practice, sometimes there is not enough water to fulfill even the most senior water rights. In an increasingly extreme climate, California state officials will face increasingly extreme challenges to implementing even the current, unjust prioritization system.

There are several commonsense changes already suggested by others that could help fix this system. None are nearly as bold as the call for outright abolition and starting over, but they are long overdue modernizations.

The proposals currently before the California state legislature to modernize the water rights system do not begin to address the historic injustices and current inequities wrought by the water rights system, but they are critical updates to make informed water management decisions and build climate resilience into our future.