I was an Agricultural Engineer. Well, technically I still am, but years ago, when I was in graduate school and discovered advocacy, I started working at the system level. Now, I am a SocioEnvironmental Systems Engineer.

Understanding the environment holistically has helped me see the web of intersecting problems and challenges that we experience nowadays in California, especially in how most agriculture is practiced. More importantly, I have realized we cannot implement a solution if it is going to create a new problem.

I love agriculture, and it is hard to see it become more and more unsustainable, contributing to negative side effects rather than being an essential part of nature. Pervasive economic incentives over the past decades made agronomists focus on maximizing profit for farm operations instead of integrating nature, sustainability, and nutrition into conventional agricultural practices. That legacy persists as an insidious mindset in many circles, especially for those who see land and water only as commodities to exploit.

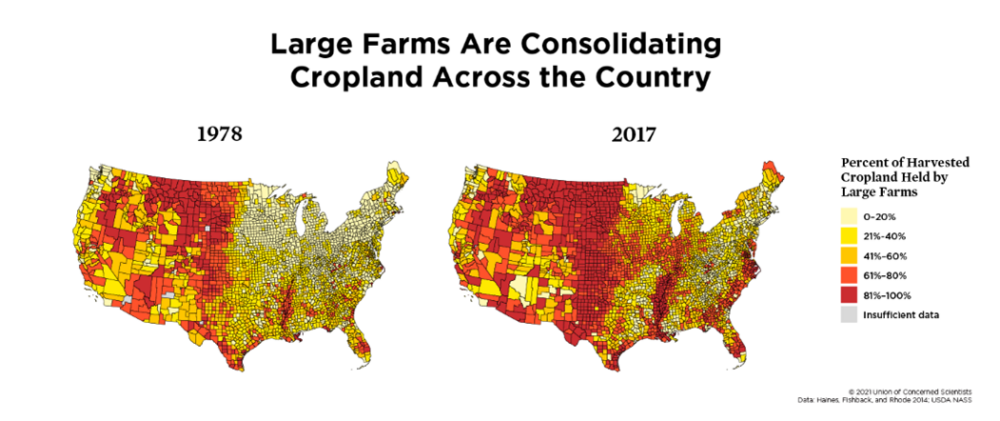

The result of decades of single-minded focus on increasing agricultural profits is seen in the chronic poverty and poor health outcomes in many of our nation’s agricultural areas. Rural regions have seen a trend towards farmland consolidation. These fewer, larger agricultural conglomerates are often disconnected from the people and the land they farm. They extract the wealth out of the soil and out of the local economy of the communities where they operate.

Who is most harmed by extractive agricultural practices in California?

There are three groups who are most harmed by industrial agribusinesses practices in California: rural residents suffering with the environmental and health effects of conventional farming, small and medium farmers increasingly pushed out and unable to sustain their farms, and farmworkers sowing fields and reaping abuse. These groups often overlap, and negative impacts become cumulative for the same people.

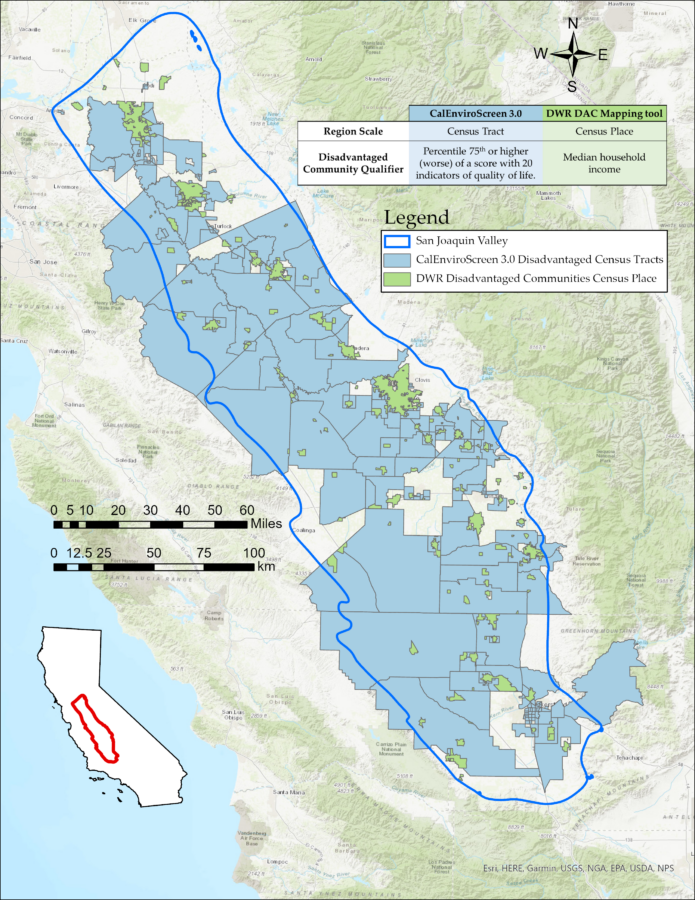

The San Joaquin Valley in California (southern Central Valley) is the most profitable agricultural region in the United States by far with a revenue of $37.1 billion in 2020. The San Joaquin Valley itself generates more agricultural revenue than any other state, and more than countries like Canada, Germany, or Peru. Other agricultural regions of California are also very profitable, such as the Sacramento Valley (northern Central Valley), the Salinas Valley, and the Imperial Valley.

However, this economic profit has a steep health and environmental toll, and that toll is paid for by the residents of rural communities in California. The three regions with the worst air quality (by year-round particle pollution) in the United States are in the San Joaquin Valley, corresponding to five of its eight counties.

I have heard stories in rural communities of nose-bleeding after pesticide spray in nearby industrial agribusinesses, and of children systematically suffering from asthma. Agricultural regions that also have oil wells, like Kern County, have even worse air quality.

Unfortunately, this industrial agriculture model also is destroying small and medium farmers in California. Too often I hear how agricultural conglomerates are buying land from small and medium farms. Many farmers don’t want to sell, even when the prices are tempting, because most farmers love the land they plough. But when megadroughts like the one facing the West today are combined with impossible water rights, some small and medium farmers have no other option than to sell to those with the economic means to bore one-mile-deep water wells.

And even on large farms, another difficult problem persists: farmworker scarcity. The main reasons for farmworker scarcity are the extreme conditions that farmworkers must endure in the field, such as killer heat for several months of the year, exposure to toxic substances, low salaries for the amount and type of work they do, and racist treatment. Furthermore, the conditions in the rural communities where farmworkers work and live with their families are terrible: extremely low air quality, water insecurity, insufficient or nonexistent infrastructure, and lack of socioeconomic opportunities. If you add restrictive federal government policies on immigration to the load of harm they are exposed to, you can easily understand why California is running out of farmworkers.

And then there’s the water problem

There is not enough water in California to sustain our current agricultural practices.

I cannot look at agricultural unsustainability and also not be deeply concerned about how it is irreversibly depleting California’s water supply. Agriculture accounts for about 80% of all the water used in California and 90% of the water in the San Joaquin Valley. In many towns, the soil sinks more than one foot a year on average due to groundwater overdraft, and water security is lacking for hundreds of thousands of residents. Equity in water access is one of the greatest threats to fundamental human rights in California.

The agricultural sector has improved its water use efficiency over the past decades with techniques like drip irrigation. But rather than saving that water, the industry has used the savings to grow more water-thirsty permanent crops (while increasing soil salinity).

Driving near the town of Firebaugh (west of Fresno County) last week, I saw another example of this disconnect between agricultural water use and our water reality: a new orchard of young perennial trees (probably almonds or pistachios) that extended about 1.5 miles long (see video below). When I looked at the current and historical satellite images of that land, I estimated the orchard covers about 750 acres and that the land had previously been planted with annual crops or fallowed. That means that this year, amidst a multi-year megadrought, while the government is paying farmers to repurpose cropland to save water (Multibenefit Land Repurposing Program and LandFlex Program), someone planted about 80,000 very thirsty trees in a place where there were no trees before.

One acre of almond trees uses 1.54 million gallons per year in the San Joaquin Valley, while one person uses about 17,500 gallons of water indoors per year in California. Those 750 acres of trees could use as much water as 65,000 Californians. And there are already 1.64 million acres of almonds in California. This farm is also located in the Delta-Mendota Subbasin, a region that just failed its groundwater sustainability plan and where rural communities experience extremely low water quality.

What I saw in Firebaugh is not unique. New orchards continue being planted across the Central Valley, even while nearby communities lack access to basic drinking water.

Agriculture can be the solution

The problems are complex but the solution is clear: we need a more sustainable agriculture. Sustainability in agriculture means social, economic, and environmental sustainability. For California to move away from its unsustainable, harmful, and water-thirsty industrial agriculture, I see the need for three major changes.

First, farmworkers and beginning farmers should be incentivized to own land and have equitable access to water. That will bring resilience to rural communities and will encourage farm work, since these new small farmers will be farmworkers of their own land. This also means improved local economies (the wealth of the community stays in the community), and more efficiency in food production and food diversity.

Second, conventional farmers can become sustainable farmers. Agroecological practices can be incentivized so that conventional farmers can transition to sustainable practices more easily. Agriculture can be habitat, and creating habitat benefits everyone. Less pesticides will mean more nutritious food (pesticides kill beneficial microorganisms that provide nutrients to the plants), and less synthetic fertilizers will mean cleaner groundwater.

Third, large industrial agribusinesses should pay for the real cost of their unsustainable production. Ideally, policy regulations can be tailored so agribusinesses reverse their current negative impacts and become socially and environmentally sustainable.

One thing is clear: we need healthy food and a healthy environment to have healthy Californians. I am still an engineer, but I look at these intersecting problems now with a social, environmental, and economic lens. Working on system solutions for the region I call home motivates me.