There is not enough water in California to sustain our current practices and everybody knows it.

In normal years and in dry years, California agriculture, industry, and households draw more groundwater than we should. And when we get wet years with deep snowpack and full reservoirs, we do not have the infrastructure to replenish the groundwater aquifers that much of the state relies on.

This deficit leaves California in an endless state of drought and at permanent risk of water insecurity, even in years like this one when it rained a lot.

Worse still, soil is sinking in some places at more than one inch per month, leading to a shrinking of California’s potential groundwater storage. That aquifer space cannot be recovered because, due to residual compaction, land sinking will continue for decades, centuries even, after a halt on pumping. To significantly reduce the land sinking process, there needs to be a significant increase in groundwater levels.

The volatility of wet and dry years, the lack of water infrastructure, and the continued depletion of groundwater resources adds up to California losing its resilience to cope with future droughts and to preserve future food security.

Agriculture is the main water user in California by far, accounting for 80% of the water use in the state. So far, all proposals to achieve water sustainability and overcome this mismatch in water supply and demand cannot be accomplished without incurring substantial economic and employment losses for the agricultural sector.

While many farmers have been improving water efficiency with drip irrigation, water savings have translated into larger areas of thirsty crops. There also have been remarkable state and federal water cutbacks in surface water, but they often have been compensated with more groundwater mining.

In other words, the water conservation efforts made by farmers have been used (especially by large corporations) as a justification to be more unsustainable with California’s water use.

The good news is we know the problem. The bad news is we are not doing enough to solve it.

But how can we solve water scarcity and water overuse without causing new problems? In other words, is there a way to reduce water use and keep everyone happy?

I believe there is: strategic cropland repurposing.

Hard truth: we have to use farmland differently

Strategic cropland repurposing is the change in land use from an economic activity that produces negative side effects (such as harming people’s health and the environment) to new land uses that produce positive side effects.

For the last four years, I have been studying in detail how to do cropland repurposing right, in a way that benefits all the involved stakeholders. Our team from UCS, the SocioEnvironmental and Education Network (SEEN), University of California Merced (Water Systems Management Lab and Sierra Nevada Research Institute), and other partners have found a way to achieve it and account for it.

Our main study, “Water, environment, and socioeconomic justice in California: A multi-benefit cropland repurposing framework,” was recently published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

But I’ll tell you the truth: this work has been hard for me. Not technically—our research team has plenty of talented professionals with sharp minds and out-of-the-box ideas. It was emotionally hard to look at the results for the first time and realize what the analysis would mean for people I know

I live in a region that depends on agriculture, and I see first-hand its impact on local communities. I really like agriculture, and objectively analyzing the effects of conventional agriculture has been particularly tough on me.

What did our study find?

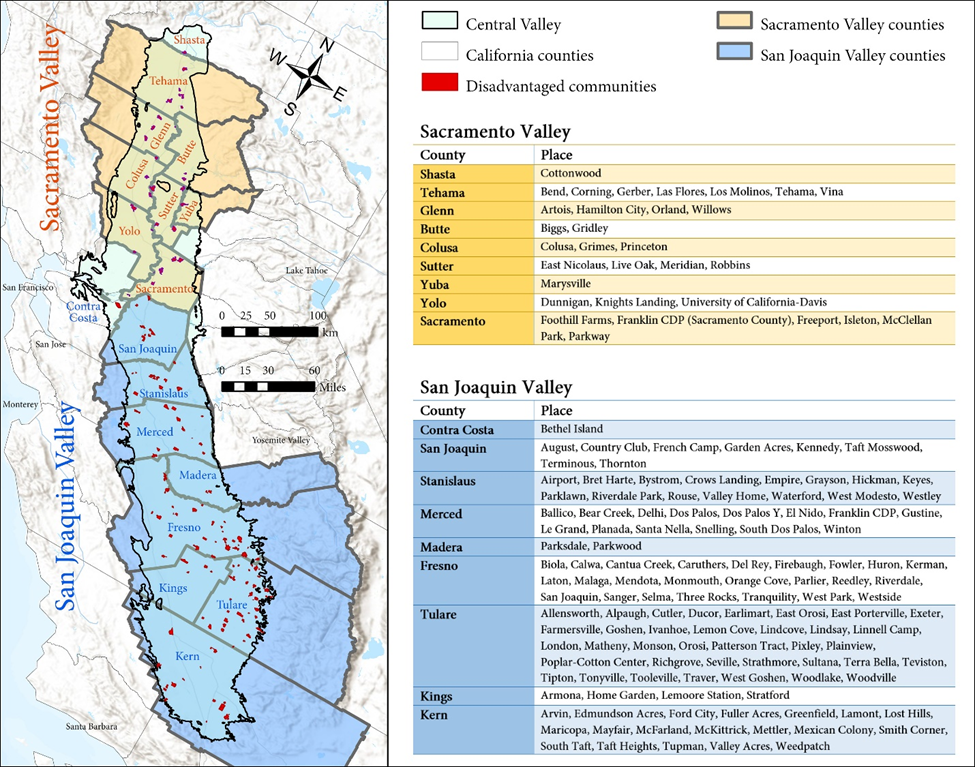

The team estimated the environmental and socioeconomic costs and benefits of retiring and repurposing cropland within a mile of 154 rural disadvantaged communities in the Central Valley. Of them, 123 communities are in the San Joaquin Valley (Southern region of the Central Valley) and are home to a half million people.

We estimated the potential of these buffer areas to contribute to reductions in water use, pesticide use, toxic nitrate leaching, and greenhouse gas emissions. We also estimated the potential for managed aquifer recharge and the economic and employment impacts of retiring the agricultural land and repurposing it for clean industries and solar energy.

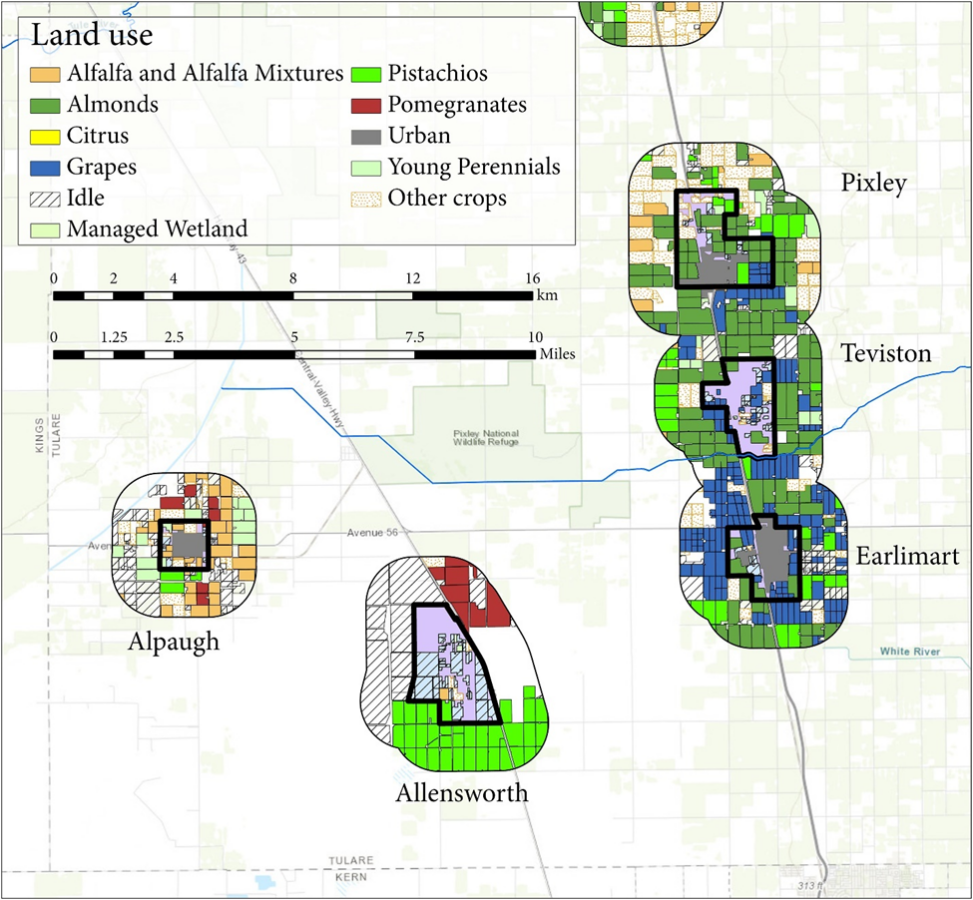

For example, current land use within one mile of the disadvantaged communities around the Pixley National Wildlife Refuge in Tulare County, about halfway between Bakersfield and Fresno, looks like this: a combination of table grapes, alfalfa (grown to feed cows, it is the most water-demanding crop in the region), almond and pistachio (the last two are both water-thirsty).

For places like the Pixley region, strategically repurposing cropland could improve the socioeconomic conditions for residents and workers by bringing new opportunities for clean industries and landowners. Over time, it could reverse the disadvantaged status of some small rural communities.

We found that retiring cropland within 1 mile of these 154 smallest rural disadvantaged communities of the Central Valley could reduce agricultural water use by 1.77 million acre-feet per year (576 billion gallons per year). That is about the same amount of water used by two-thirds of all Californians (26 million people) indoors in a year. That annual water use reduction would be equivalent to the current average estimate for the San Joaquin Valley’s water overdraft of 1.8 million acre-feet per year.

If we considered only the reduction in groundwater use in that one-mile buffer around those communities in the San Joaquin Valley, it would result in a water use reduction of more than 40%, although the affected area only makes up 11% of the total agricultural land. If the water use was reduced by repurposing cropland at the same time that excess winter flows from the Sacramento Valley were brought into the area, that combination could recover up to 80-90% of the current estimated overdraft in the San Joaquin Valley on average, (although, under current drought forecasts it may not be enough given the expected drier future).

Health and environmental benefits beyond water reduction

Retiring cropland within 1 mile of the 154 smallest rural disadvantaged communities of the Central Valley also could reduce agricultural nitrate leaching into local aquifers by 105,500 tons per year (233 million pounds per year). That is about one pound of toxic nitrate per person per day that leaches into and near community aquifers that could be stopped.

Agricultural nitrate comes from fertilizers and is linked to several health conditions, including “blue baby syndrome”, miscarriages, and other conditions. Synthetic fertilizer use is also remarkably inefficient: more than 50% of the fertilizer applied in California’s Central Valley is leached into local aquifers, while 10% turns into potent greenhouse gases, and 5% is lost to runoff. Only about one-third of the nitrate applied as synthetic fertilizer stays in the soil and is used by crops.

Cropland repurposing that led to the reduction of fertilizer use and nitrate leaching would result in a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (mostly nitrous oxide) equivalent to 2.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. That is equivalent to what half a million fossil-fueled cars emit annually.

The results of the study get even better the more you dig in: cropland repurposing could also have a huge positive impact on local residents’ and workers’ health.

As I’ve written about before, it is tough to hear the stories of seniors whose noses bleed after pesticide spray and of systemic children’s asthma in rural disadvantaged communities surrounded by industrial agribusinesses. Pesticide drift exposes people nearby to an alarming amount of pesticide breathed in or landing on their skin, clothes, and inside their homes. Retiring cropland within one mile of the 154 smallest rural disadvantaged communities of the Central Valley could reduce the use of 5,388 tons of pesticides per year (about 12 million pounds per year).

Repurposing cropland could mean water security

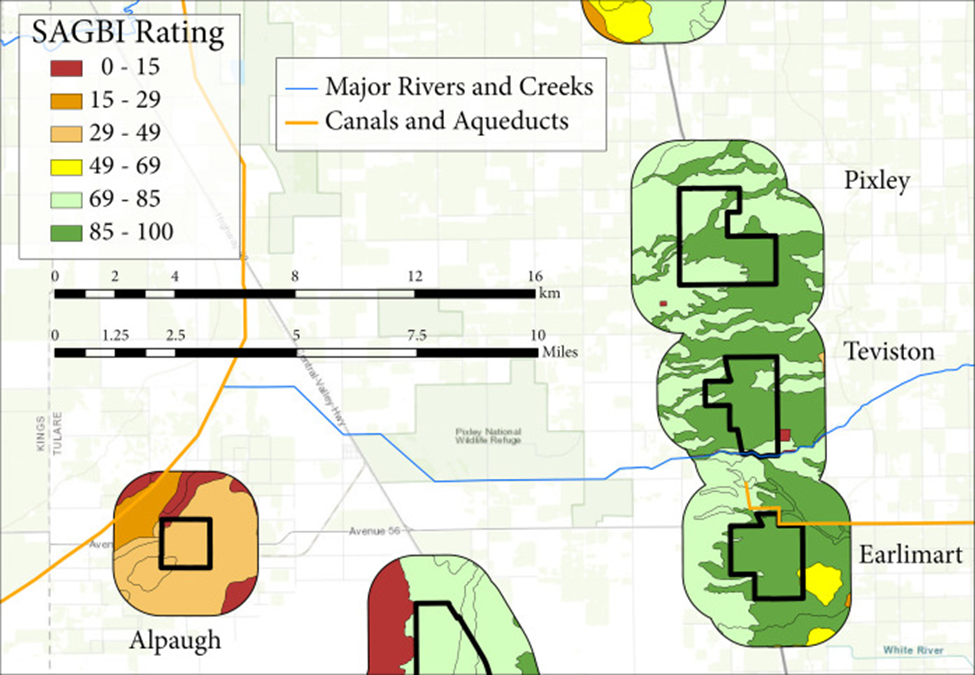

In the Central Valley, 64 small disadvantaged communities (42% of those studied) are crossed by a river or a canal, of which 48 have an excellent recharge banking potential.

Out of the 154 communities, 139 have moderately good or better recharge banking potential areas. Of those, 99 communities are within one mile from a canal or a river.

In the southern part of the Central Valley known as the San Joaquin Valley, 73 communities are within a mile from a river or a canal and also have moderately good or better banking recharge potential.

For example, Teviston in Tulare County has excellent soil groundwater banking potential: it is crossed by a river, and it is about 0.6 miles away from a canal. Yet, Teviston needed drought relief because of the 2012-2016 drought and their wells failed again in 2021. Teviston is one of the many clear examples of how land repurposing can provide water security for California.

Aquifer recharge also has the potential to increase groundwater storage, reduce groundwater overdraft, and increase hydropower generation without substantially impacting environmental flows.

Economic improvement for rural disadvantaged communities

Retiring agricultural land is controversial because it causes revenue and employment losses. But a close look at the numbers found in our study revealed a more positive outcome worth considering.

The potential aggregated losses of retiring cropland within one mile of each community could be up to $4.2 billion per year and a reduction of 25,682 job positions in the whole Central Valley paying an average of about $45,000 per year per job position. Often, one job position in agriculture can be shared between two (or more) people, meaning that actual farmworker salaries are normally far less than the average.

Only retiring the cropland within one mile of each community averages a $27.3 million loss per year in agricultural revenues and 167 lost jobs in total per community.

But the potential benefits of investing $27 million per community for ten years via cropland repurposing are up to $15.8 billion per year and 62,697 new jobs for the region. That averages $103 million of new revenues per year per community and 407 jobs per community.

In total, this scenario results in an annual equivalent value of $11.4 billion per year and 37,014 jobs paying 67% more on average—an economic win for areas that have been historically disadvantaged.

This is why cropland repurposing must be done strategically; we must ensure it is undertaken in a way that offsets the potential cost with more revenues and better job opportunities. (Read more about our methodology here).

Will we grab the opportunity in front of us?

Imagine with me what the future for these communities in the Central Valley can look like: instead of an agriculture-only economy, the state of California and private interests invest $27 million dollars per disadvantaged community per year for ten years in clean industries and clean energy, such as solar energy generation and battery storage. The revenue for the following 30 years would be $15.8 billion per year with an addition of 63,000 jobs paying an average 67% more than what typical farm work jobs in the region currently pay. There would still be plenty of land for green areas, aquifer recharge, wildlife corridors, and other opportunities, and we’d get plenty of water savings and public health benefits.

I often recommend combining solar panels with wildlife corridors or with aquifer recharge projects. That is the perfect example of a multi-benefit project that saves water, generates new revenues and better employment, improves the environment, and preserves the health of the neighbors.

The hard truth is that agriculture is using more water than we have. Figuring out what we do with California’s farmland is a hugely important challenge ahead of us, but we have the opportunity to make it work for everyone. By prioritizing sustainability and justice and combining smart farming and clean industries, we can increase the social, economic, and environmental resilience of rural communities and agriculture. By incentivizing the creation of positive side effects, we can foster local economies and thriving communities where everyone, locally and in our larger society, benefits.