This report was co-authored by Juan Declet-Barreto

If you are like me (and I know many people are), you plan your vacations around national parks. There’s so much to see: beautiful nature, great history, historical lodges, and nice infrastructure. The perfect getaway for me always includes a national park.

The lure of getting away from civilization to be immersed in gorgeous scenery is strong, with the National Park Service recording 312 million recreational visits last year. However, visiting during the summer now comes with added dangers. The US is experiencing some of the hottest weather in history, meaning that even the best planned vacations can quickly take a turn for the worse—even for those experienced with hiking, camping and other outdoor activities.

You don’t have to be miles and miles into the backcountry before the heat can turn deadly, and sometimes bad decisions can put a person in a dangerous situation when it comes to heat. You might have ignored the high temperature warnings when you hit the trail because when you headed out it didn’t feel too bad.

I mean, you’ve saved up precious vacation time so there was no way you were NOT going to hike, say, to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, or perhaps do a full roundtrip hike for which you had to get a permit. You’re fit. You’re a good hiker. You know you can do it.

Unfortunately, Danger Season—the period between May and October when climate change is making extreme heat much worse and common—is making those assumptions a lot more hazardous.

Let’s talk about the searing heat

June 2023 was the hottest on record, and we saw in July a stretch of the hottest days in recorded history. It is very likely that 2023 will be among the hottest years ever recorded, if not the hottest. Not surprisingly, these relentless extreme heatwaves, not just in the US but around the world, would be almost impossible without global warming, according to a new international study.

Heat kills more people than hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, and other weather events that are usually seen as more catastrophic. Unlike these other weather extremes, which arrive full-force and leave devastation of homes and infrastructure in their wake, heat is stealthier. It can come one day and then stay for days, weeks, or months, as we are seeing this year.

According to the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics, “during 2004–2018, an average of 702 heat-related deaths (415 with heat as the underlying cause and 287 as a contributing cause) occurred in the United States annually.” This information in itself is telling, because it is a well-known fact that deaths attributable to heat are historically undercounted. A study from 2020 found that the number of deaths related or attributed to heat in the United States is larger than previously reported when based on the number of death records that list heat as the cause of death.

The heat in national parks, a handful of them located in some of the hottest places in the United States and even the world (Death Valley hit 128°F a few days ago!), has taken its own toll in fatalities this year. Heat is the suspected cause in the death of five people since June, all in parks in the US Southwest. Tragically, this included the death of a young boy and his stepfather, as well as park visitors of advanced age. And this is before the historically hottest month of the year—August—has even started.

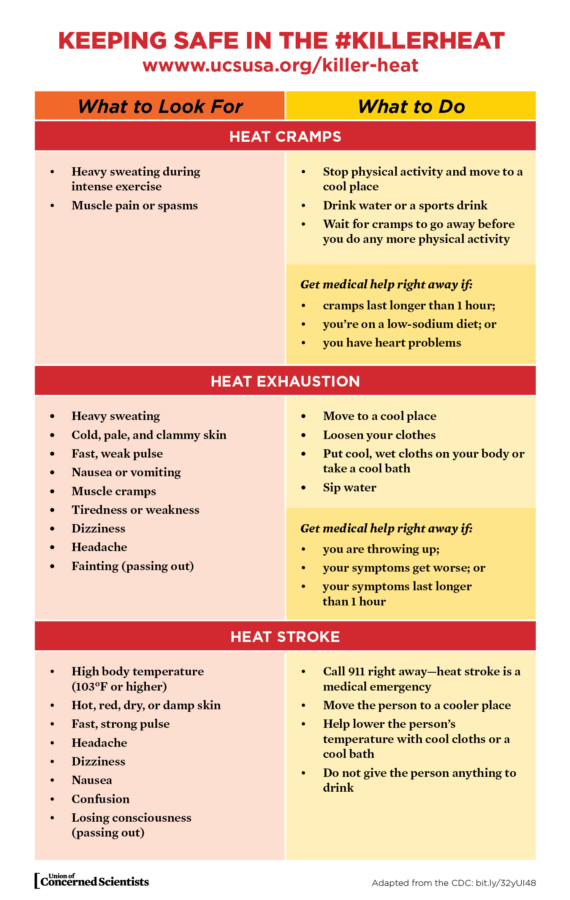

Heat can be not only deadly, but also have significant impacts on one’s physical and mental health. Heat can affect our physical bodies in myriad ways (see figure below), and what it does to our minds can be debilitating and have broader impacts on our day-to-day functioning. A colleague at the Union of Concerned Scientists who used to live near the desert recently mentioned that “it was the third month of 100+ temperatures” that got her each year.

Heat illnesses are insidious because the symptoms can creep up on you, and while you may feel like you can muscle through, particularly if you’re fit, coping with heat is not related to physical stamina.

National Park Service sites are being impacted by heat

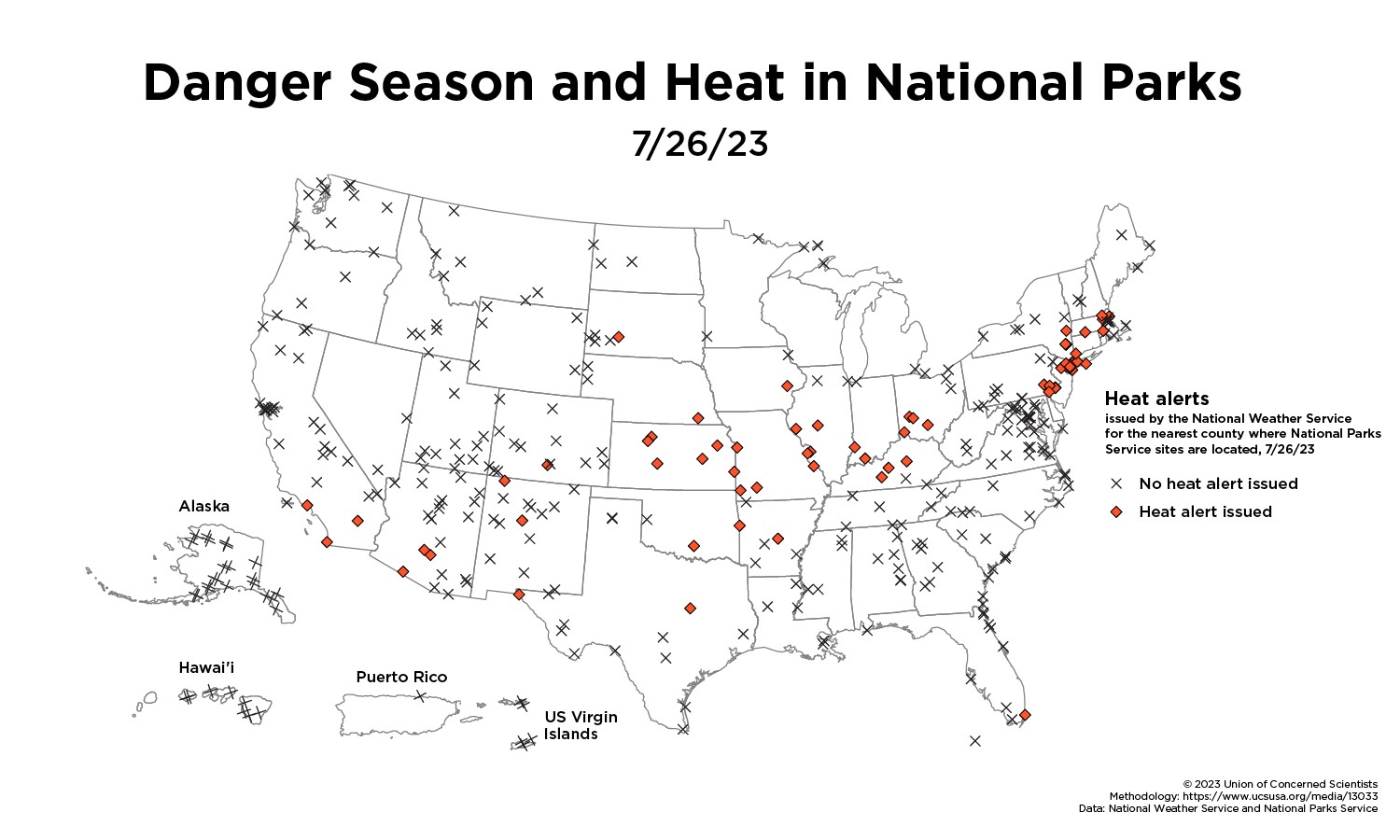

After shattering records in the Southwest this month, the Midwest, South, and parts of the Southwest are in heat’s grip. And the heat is moving into the Northeast very soon. We have mapped NPS sites across the country and overlapped them with heat alerts issued by the National Weather Service (see how we keep track of daily extreme weather alerts in our Danger Season page). On July 26, 2023, there were 73 parks under heat alerts (figure below), across 23 states and territories.

We also overlaid heat alerts for July 26, 2023 on NPS sites, finding that 255 out of the 394 NPS sites we looked at (with the exclusion of trails or rivers) have been under at least one heat alert since the start of Danger Season on May 1st. This amounts to 65% of all NPS sites we looked at. Some, such as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona and Chamizal National Memorial in Texas have seen more than 32 alerts!

Note that Dry Tortugas in Florida, a 100-square mile park in mostly open water with seven small islands, is marked as having no heat alerts (because such alerts are for air temperature, not water). However, we have seen that the temperature of the ocean water off Florida and the Keys is particularly high this year—record-breaking hot, in fact. The water temperatures are extremely relevant for that ecosystem, as well as for other parks such as Everglades and Biscayne National.

Click here to access the data and methods for the NPS and heat alerts analysis.”

The National Park Service tries to protect people from heat-related illnesses

Parks such as Death Valley post signs, including at trailheads, warning visitors about extreme heat dangers. They also alert visitors that they may not be able to come to their rescue during extremely hot days, so not planning properly can equate to trouble at best and a death sentence at worst.

It’s not clear that the message is getting through based on the number of photographs on social media of people near thermometers displaying super-high temperatures—a sign some visitors are seeing heat as more of an attraction than a hazard. Don’t be fooled.

The NPS also has a website specifically addressing heat, with tips on how to “Beat the Heat” that include the explanation of what a heat-related illness is, how to plan for the heat, how to pack for the heat, how to avoid heat-related illness during your activity, and what to do when experiencing a heat-related illness.

Know the symptoms of heat-related illnesses, and what action you should take. The infographic below comes from our own Killer Heat analysis and is a good resource to have handy.

It’s not just the heat

During Danger Season, we can count on killer heat to be a constant presence in many parts of the country, as this year is showing us. On top of that, the many extreme events that have the potential to happen during the hottest months of the year—hurricanes, extreme precipitation, flooding, drought, and wildfires—can all negatively impact the natural and built environment of national parks.

Our Danger Season mapping tool displays daily extreme weather alerts across counties in the US and its territories not only for heat, but also flood, storm, and fire weather conditions that make wildfires more likely and destructive.

The map tracks the severity of Danger Season through daily alerts data from the National Weather Service. Our friends at Climate Central provided the data that directly connects heat alerts with climate change. And before you wonder, yes, climate change has worsened heatwaves, as well as floods and wildfires.

This heat is exhausting. And so is the continued use of fossil fuels—the root cause of the brutal heat and high temperatures that are fueling the climate crisis. We must stop fossil fuel extraction, processing, and use now. We must demand accountability from those responsible for destroying our planet and messing up our vacation plans. Stop oil and gas companies now.