This summer, also known as danger season, already has seen record heat waves, drought, and floods. It continues a trend of recent summers that saw record flooding, major hurricanes, and severe wildfires unlike what many of us can remember from our lifetimes.

When these types of events happen, they are often couched in terms of an event once-every-x-number-of-years. But what exactly is a 50-year, 100-year, or 1,000-year weather event? And is that kind of description even relevant as the planet heats up and climate change changes everything?

Let us break down what is really meant by those terms and figure out if that language is effective at conveying the rarity and severity of these events.

What was rare is becoming more common

People have been observing various aspects of weather for an exceptionally long time. Stories about remarkable weather events have been retold through the ages. When we share weather and climate stories through news headlines or via video, we often put these into context and compare them with prior events.

Consider the case of a seasonal event that happens each year like the spring ice breakup on a river. Riverside communities historically have known and obsessed about the dates of ice breakup because they depend on the river for transportation, hunting, fishing, and commercial needs. That yearly event depends on many weather-related factors in the region.

In Alaskan and Canadian communities near the Arctic Circle, prior experience dictates that it would be extraordinary for river ice to break up in the middle of April when communities expect freezing temperatures. It used to be quite rare to break up around the last days of April and start of May, but possible within the range of observations. But today, in places like Nenana, Alaska and Dawson City, Yukon, river ice breakup often occurs around a week earlier than a century ago. In this case what used to be quite rare (only once in a generation, or once in a lifetime) is now more common. Younger generations are learning to expect the yearly ice breakup sooner, around the turn of the month from April to May.

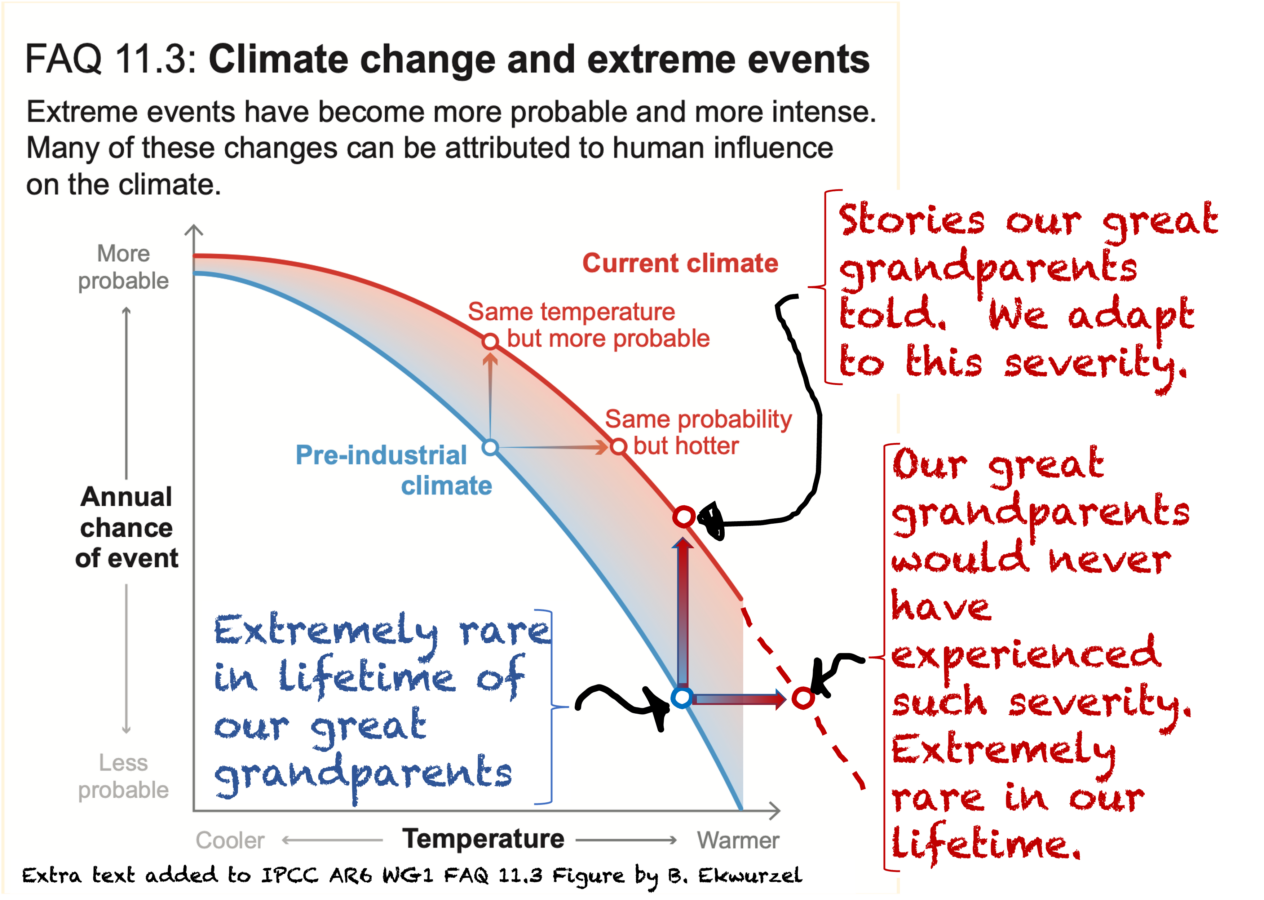

A similar change is happening with record hot temperatures in places where extreme heat is no longer unheard of (see figure with extra labels added to IPCC AR6 WG1 FAQ 11.3).

A person who lives in London, as did their great-grandparents, might have heard through intergenerational stories about a rare heatwave that disrupted a summer day. Yet, their great grandparents never experienced summer days with 40 degrees Celsius or hotter as London residents did last month. The first date ever to record 40°C in the UK was July 19, 2022.

The UK heat wave this summer was not just a rare event, it was an event of a severity that had never been recorded! Scientists were expecting this day would come, although not likely two years after they published their paper.

The UK Met Office scientists back then assessed that summers with hot days like the ones this summer are exceedingly rare (currently 0.3% to 1% chance in any year). Though increasingly possible. Those tiny chances just happened, and a threshold has been crossed for the record books.

Like young people in the Arctic Circle experiencing hotter temperatures than their elders can remember, London youth will much more often experience what was rare or unheard of for older generations. Thanks to climate change.

Once-every-100 years does not mean what you think it does

It is common for people to think that when they hear once every 50 or once every 100 years that the higher the number of years, the rarer the event is. This makes it sound like we must wait for years to see such a magnitude event. But that is not what it means.

A 100-year flood level means a 1 in 100 or 1% chance of exceeding that water level in any given year. Every year there is a 1% chance of that magnitude flood occurring. It could happen several years in a row, but each one of those years there is only a 1 in 100 chance of it happening. Add climate change and we need to keep track of which decade these flood levels were determined. For example, with expected sea level rise over the next few decades what currently would be extreme coastal floods (50-year floods or a large flood with only a 2% chance in any given year) are likely to occur annually for most coastal U.S. regions.

Hurricane Harvey in Houston is another example of this. It was a major hurricane in 2017 that underwent rapid intensification and stalled between two opposing pressure systems. The result was that Hurricane Harvey rainfall exceeded the 1000-year extreme precipitation for the Houston metro region. Some scientists described this event as Harvey setting up a hose that sucked the water from the surface and dumped it on the metro region over several days.

How can forecasters and public officials even warn residents about a flood so big there is only a 0.1% chance it happens in any given year, and how do city planners, residents and businesses plan for an infrastructure that can withstand that magnitude of flood more often thanks to climate change? The extreme precipitation Houston saw under Harvey will be less rare in coming decades.

Caveat: record period is key for understanding how rare an event is

Have you seen news like this:

- The period from May 2018 to April 2019, was the wettest 12-months over 124-year record for the contiguous US.

- Since 1990 Western Mongolia summer temperatures are the warmest (over 1269 – 2004 C.E.).

- Southwestern North America just logged the driest 22-year period in at least 1,200 years.

When considering how rare events are becoming more common, it is important to take note of how long we have been keeping records. Record length is key to providing context for any extreme weather event that might occur. This helps scientists and non-scientists better understand if this event is just another example of the common catchphrase “weather is always changing” or if the weather event truly is “off the charts?”

Climate change is increasing severity and consequences of extreme events

Extreme event probability and associated severity is changing. It is now more likely for many communities to experience unprecedented extreme weather events. According to the IPCC, now and in the coming decades, extreme events will occur with various combinations of larger magnitude, increased frequency, new locations, or different timing (IPCC AR6 WG1 FAQ 11.2).

Now that human-influenced extreme rainfall event is more likely, China and the US have this in common: figuring out what kind of flood risk we can expect in the places where such intense rain falls and preparing for it. A record-breaking rain event in Sichuan Province, China during August 2020 now has double the chance of occurring compared with historical chances. Overall, for the US, outdated 100-year flood zone maps represent around a 40% undercount such that many more homes are in the current 100-year flood zone.

How communities prepare for the more common severe weather-related events can go a long way to increasing survival and resilience to endure and recover after an unprecedented weather event.

Unfortunately, in too many cases of extreme flooding and heat waves, the trend is not encouraging.

- Development in Houston, including increased impermeable surface area (e.g. parking lots and concrete lined drainage), further increased peak stream discharge when Hurricane Harvey dumped unprecedented rainfall.

- Cultural factors, building design, and social isolation proved lethal in Paris during the unprecedented 2003 heat wave.

We can do better. Already, lessons learned from the events above are improving planning decisions, emergency response in those regions and many other parts of the world who know they could be next. We can learn from parts of the world where people have developed resilience to similar events that are common there but previously rare in other areas: in other words, Seattle must learn from Phoenix how to deal with extreme heat, and Phoenix could learn from Abu Dhabi about water supply solutions.

We need innovative words to describe extreme weather events

Sometimes the math and our language fails to convey how absolutely in uncharted territory we are with climate change.

Researchers from over twenty institutions from around the world assessed a deadly 2021 Pacific Coast heat wave in Canada and the US border region as a one-in-1,000-year event. When asked about the rarity of that heat wave at a scientific society meeting earlier this year, one of the co-authors was temporarily at a loss for words to describe the event. They said it was hard to grasp typical mathematical approaches as was done in their paper. The heat wave was so rare, so severe, so unimaginable, it would be like if the heat wave were a pink elephant with polka dots—that is, never seen or imagined.

The folks in Canada last year or in the UK this year found themselves truly in uncharted territory. What do we do when a heat wave (or other weather event) as rare as a pink elephant with polka dots occurs in a region unprepared for such a strange event? What language can we use to warn people ahead of time?

The language around our math has to start changing in part because statistics from the past are often insufficient to describe some of the unprecedented events we are experiencing today. Let alone the future world hurtling toward 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees Celsius global average temperature.