The scale of the tornado outbreak in early December 10-11, 2021, is hard to fathom. Missouri. Illinois. Arkansas. Mississippi. Tennessee. Kentucky. Wind ripped roofs off as if they were a tarp covering a wood pile and carried vehicles unimaginably far away. Rescue efforts are still underway. The mourning has begun for far too many families.

Questions are already being posed to governors, utility companies, and FEMA. Is this as rare and improbable as it seems, and how does climate change factor in? How fast can the power be restored? When can heat, supplied via natural gas lines, or water become available? How much support can FEMA provide? So many more questions will be asked in the days ahead.

Science may be able to provide some clues.

Is this early winter tornado outbreak rare for the US?

If conditions align, it is possible to have a tornado occur somewhere in the continental U.S. any time of the year. However such severe tornadoes are rare this far north (i.e. Illinois and Kentucky) in early winter.

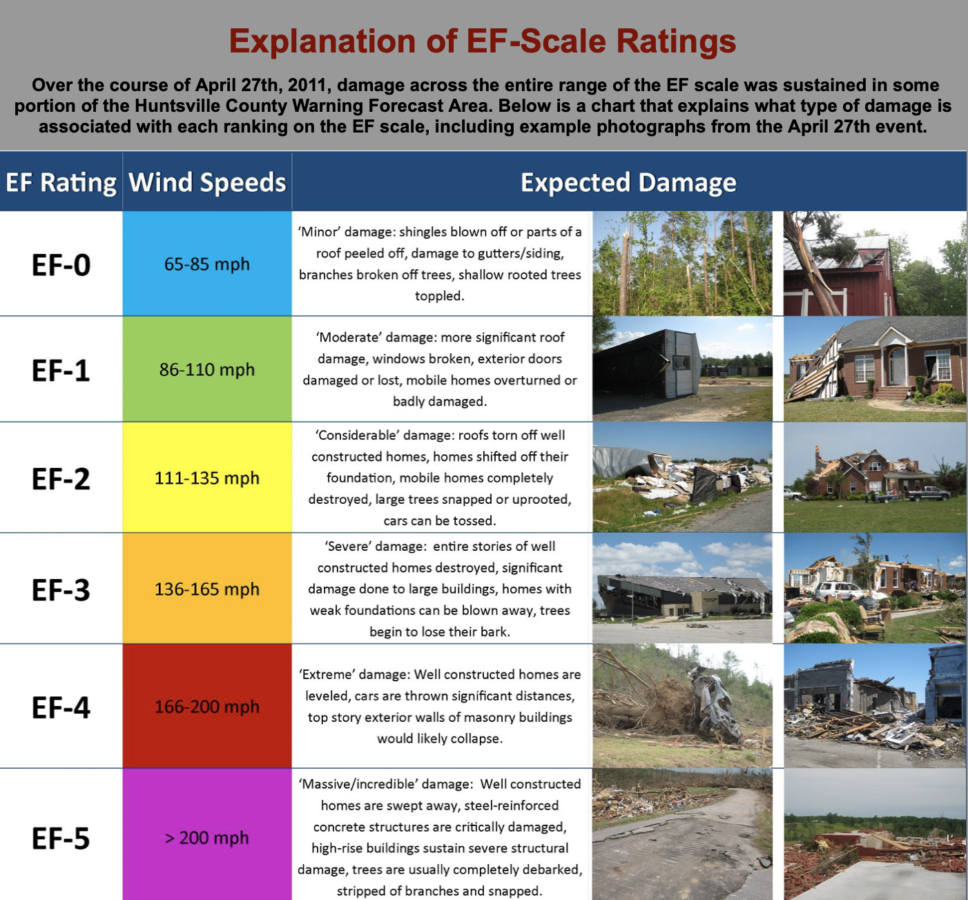

The National Weather Service crews are on the ground investigating the damage for official Enhanced Fujita(EF) scale rating based on estimated wind speed and related damage. Early reports suggest an EF-3 or stronger tornado in Edwardsville, Illinois was associated with a warehouse collapse. The National Weather Service indicated an EF-3 or stronger tornado destroyed a candle factory in Mayfield Kentucky. Families in Dawson Springs, Kentucky likely experienced an EF-3 or stronger tornado. And an EF-3 or stronger rating for Bowling Green, Kentucky tornado damage is likely.

Preliminary assessment says one may have been the longest track ever recorded for a tornado. On Friday evening December 10, 2021, an EF-3 or stronger tornado touched down and likely twisted continuously on the ground in Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee, and Kentucky.

Is it unusual for there to be so many tornadoes in close succession?

Researcher Michael Tippett and colleagues found a trend toward more tornadoes in the most extreme tornado outbreaks since the 1970s with an associated trend for less tornado activity during periods in between tornado outbreaks.

A tornado outbreak is when six or more EF-1 or stronger tornadoes occur in close succession. Researcher Christopher Furhmann and colleagues point to both the track length of tornadoes and EF scale strength as key factors that determine the level of danger tornado outbreaks present to people. These researchers point out that most tornado outbreaks occur with larger weather patterns that last over a significant chunk of a 24-hour period. That means forecasters have a greater chance to identify tornado risks and issue advanced weather warnings to help communities find safe places earlier.

Most common region for tornado activity has shifted east

Popular references to tornadoes in film often evoke U.S. states in the Great Plains with twisters depicted churning in the distance. Flat landscape where the sky dominates. So it’s no surprise that Norman, Oklahoma, is a major place of research where government and university collaborators focus on tornadic thunderstorms.

Scientists who track tornadoes are noting a shift in the epicenter of meteorological conditions that may spawn tornadoes toward places with landscapes that typically obscure many sight lines from the ground where one could potentially see a tornado on the horizon.

Meteorologist Bob Henson describes the shift from the Great Plains to east of the Mississippi River, south of the Ohio River and west of the Appalachians as the epicenter for EF-1 or stronger tornado frequency. Accordingly, the season for this early December tornado outbreak seems to confirm this trend.

Researchers Vittorio Gensini and Harold Brooks found that for the December, January and February season between 1979 and 2017 measures of the characteristics of weather conditions associated with tornado reports decreased in southeast Texas and increased in the epicenter region described above. Gensini and Brooks describe in greater detail how these geographic trends shift as the seasons cycle through the continental US.

Are these tornadoes linked to climate change?

The potential connections between climate change and tornado activity are relatively challenging when compared with the connections between climate change and other types of extreme weather, such as heat waves or intense precipitation events, primarily because tornadoes are notoriously small-scale events and hard to detect with observations.

The thunderstorms that spawn tornadoes are more readily observed. Favorable conditions are no guarantee a tornado may form or what the strength would be. In the past, a tornado strength was based on damage surveys. Over time, the situation has improved with evolving satellite sensors and better ground observations. Still, damage assessment reports are part of the final determination.

Reliable tornado metrics that could be part of climate models are still a challenge for meteorologists and climate researchers. That’s in part because there are many factors involved in tornado formation. One of those factors—having warm, moist air available despite it being December—is likely to become more frequent in the US with climate change and may have played a role in enabling this most recent tornado outbreak. The early winter conditions have been remarkably mild in the continental U.S. with over three thousand record highs already recorded for December.

A particular type of thunderstorm that meteorologists refer to as “supercells,” are associated with tornadic thunderstorms. A key ingredient is wind shear, when wind blows from different directions at various heights in the atmosphere. A tornado can form when colder and drier air blows higher up in the atmosphere while warmer and moister air blows in a different direction near the surface. In between the winds can form a rotating horizontal tube of air as the warmer surface air rises while the cooler air sinks. Thunderstorms typically involve warm surface air that rises into the storm. Such an updraft can shift a rotating horizontal tube into a vertical rotating tube of air. The storm can continue to rotate and become a supercell. In rare cases a supercell can form a funnel cloud that may touch the ground and become a tornado.

Warmer temperatures and higher moisture levels increase the amount of energy available to the storms that can spawn tornadoes. Both temperature and moisture levels are expected to increase with climate change, the latter because a warmer atmosphere can essentially hold more water vapor. However, more research is needed to get a handle on how some of the other conditions necessary for tornado formation—such as wind shear—might change with further climate change.

Tornado Warnings

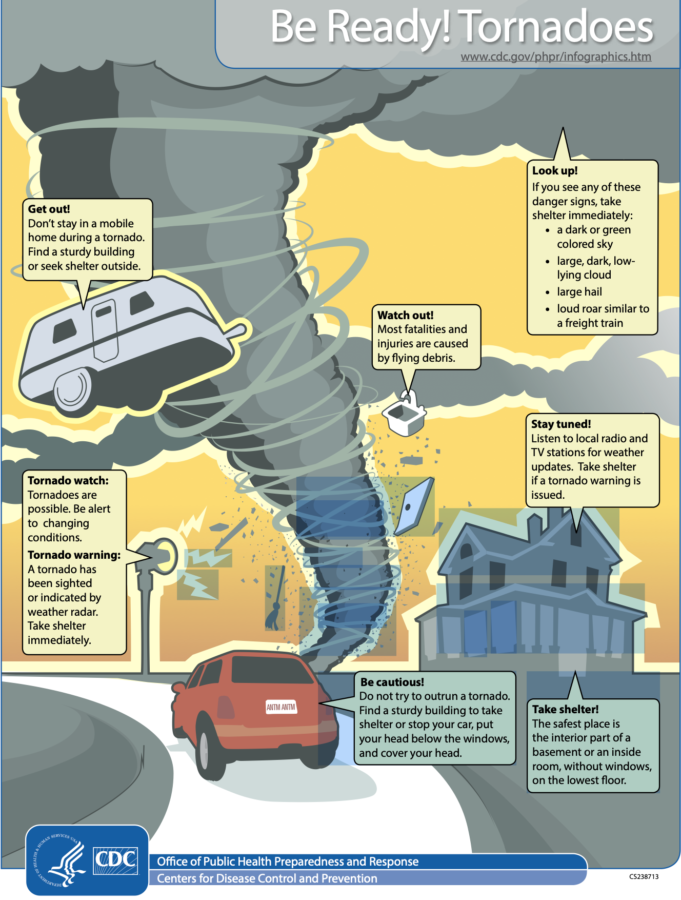

The NOAA storm prediction center gave notice a day in advance of the storms that hit on Friday and a tornado watch for the afternoon and evening was issued for Kentucky that day. The National Weather Service office in Paducah, Kentucky, gave a tornado warning about 20 minutes in advance for the Mayfield, Kentucky region. This was upgraded to tornado emergency as the powerful tornado passed through.

It is more than worth it to invest in ways to improve weather forecasts and communication of the risks with such powerful extreme events. Just as important is investing in improving the factors on the ground that reduce exposure and vulnerability, especially for communities that may be exposed to greater risks as tornado activity increases for different areas.

You can help. See my colleague Alicia Race’s blog post for resources to support the Kentucky recovery effort.