On a recent trip to Chicago, I took some time to visit the Lincoln Park Zoo. The highlight for me was the Great Apes Hall, and while I enjoyed seeing the chimps and the gorillas, they didn’t have the ape I was hoping most to see, an orangutan. It may not be too surprising that there are no orangutans in Chicago in winter, but even in their native habitat they are increasingly difficult to find, as their populations have declined by 50% on Borneo and 80% on Sumatra. A recent paper published in the online journal PLOS ONE helps shed some light on the current distribution of those few remaining wild orangutans.

Populations of orangutans have plummeted by as much as 80 percent, and habitat loss is a major driver of their decline.

What determines distributions?

The study looked at factors affecting the distribution of orangutans across the island of Borneo. The researchers compiled over 6,000 data points ranging 1990-2011. They examined a number of factors affecting the distribution, including annual rainfall, land-use type, mean daily temperature, soil type, and others. They found that the two most important factors for predicting the presence of orangutans were rainfall and land-use type. While the rainfall finding is interesting from a scientific standpoint, it was the details of the land-use finding that really struck me.

A place to call home?

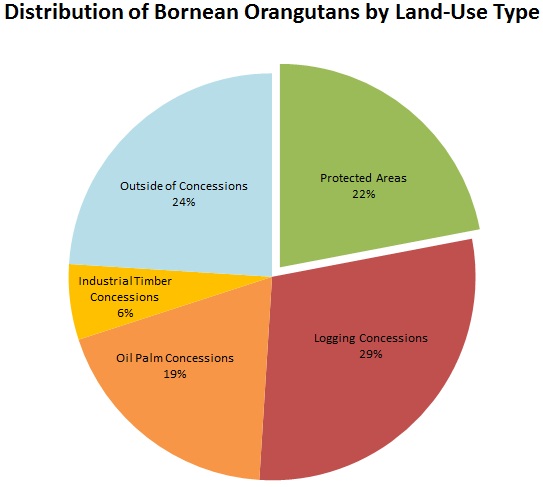

The researchers classified land use into 5 categories: Protected areas, which are theoretically off limits to human disturbance (but which do suffer from some illegal logging, hunting, and farming); logging concessions, which allow for some selective logging but which can’t be clear cut; industrial tree and palm oil concessions, forests that can be (or already have been) clear cut and converted to either palm or timber plantations; and finally areas outside of concession, basically the miscellaneous category. The pie chart below shows the percentages of the populations found in each land-use type:

This graph shows the distribution of Bornean orangutans by land-use type. Over three quarters of the population exists outside of protected areas.

What strikes me (and the authors) about these findings is that over three quarters of the orangutan habitat is outside of protected areas and is therefore at risk of being cleared. Such clearing could cause the existing populations to plummet. The authors estimate that clearing forests for timber plantation would result in the death or displacement of more than 95% of orangutans in that area and describe palm oil plantations as “the poorest land use type” for the ape.

How do you define sustainable?

This study comes at an important moment in the debate over sustainable palm oil, as the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is in the process of reviewing its principles and criteria (P&C). The current P&C does limit development in forests where orangutans are present; however, they still allow clearing of logged and secondary forests (often categorized as “degraded” forest), which, as this study demonstrates, can provide potentially important habitat for orangutans. Over 200 scientists (including the lead author of this paper) signed a letter urging the RSPO to make clearing of these types of forests off limits. Let’s hope that the RSPO takes steps to protect secondary forests, which could provide vital habitat for orangutans before it’s too late.