Sixteen years after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, the city has been slammed by another record-breaking storm: Hurricane Ida. A new analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) reveals that 138 industrial facilities in and around the city—some of which use electricity to contain hazardous chemicals—are potentially without power, putting facility workers and nearby civilians at enormous risk.

Watching and waiting

Now, with recovery efforts in New Orleans underway, we are waiting to hear about potential releases of toxic chemicals from factories, water treatment plants, and chemical facilities in the area. These preventable accidents are all too common after natural disasters and pose a threat to the communities at the fenceline—those living near industrial facilities which are often predominantly communities of color and low-income communities.

The most recent data show that EPA’s National Response Center (NRC), which tracks oil and chemical spills and releases, has received 39 reports, 17 of which indicate toxins leaked in the air (as of September 6th, 2021). Other sources say there have been upwards of 300 chemical and oil leaks in the Gulf. The Louisiana State Department of Environmental Quality has confirmed releases of “crude oil, fuel oils and a variety of chemicals” throughout southeast Louisiana. There have also been reports of excessive gas flaring at a Shell Norco Refinery. With air pollution monitors in the area out of commission due to power outages, we have limited data on the impact these events have had on air quality in the region.

The coming days will be critical; As workers return to facilities and factories begin to restart operation, the risk for disaster is elevated as the period in which facilities start-up operations is known to be extremely dangerous.

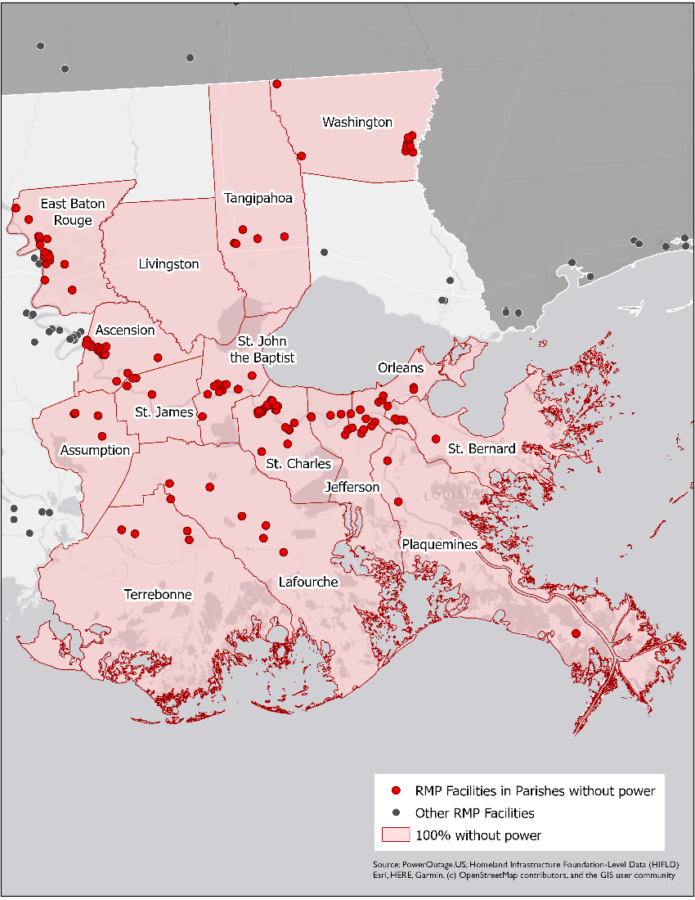

UCS analysis finds 138 RMP facilities in areas without power

After news broke of Louisiana’s massive power outages, we worked quickly to identify the number of facilities regulated under the EPA’s Risk Management Plan (RMP) rule that would be affected by the outages. We found 138 RMP facilities in the parishes with complete or nearly-complete power outages. This means that, without back-up power, chemical releases, fires, and explosions can occur.

This does not mean that all 138 facilities are without power; many likely have back-up generators. But back-up power is not required at these facilities, and back-up power systems have failed before. The situation makes clear the dangers these facilities pose to workers, first responders, and the surrounding communities in the Gulf Coast region.

What is RMP?

We mapped many kinds of facilities, from factories to wastewater treatment plants, but they have one thing in common: all are regulated under the EPA’s Clean Air Act Accidental Release Risk Management Plan (RMP). The RMP rule requires certain facilities—those that store and process chemicals that, in the event of a toxic release, could endanger workers and communities—to assess, plan for, and mitigate risk for chemical disasters.

But RMP requirements are lacking in a variety of ways, and the potential impacts are frightening. For example, when Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in 2017, floodwaters breached the Arkema Crosby chemical plant just outside Houston. Although Arkema was partially regulated by the RMP rule and had plans in place for hurricanes, the facility was not prepared for “Harvey-level” flooding. As several feet of floodwater inundated the plant, its back-up generators failed, shuttering the plant’s ability to refrigerate—and control—its toxic chemicals. These chemicals became unstable, resulting in explosions and fires that lasted several days after the storm. As a result, residents living within a mile and a half of the facility were evacuated and 21 individuals sought medical attention from exposure to smoke and fumes from the incident.

The Arkema facility was built before flood maps had been created for the area. The first flood map for the area – from 1985 – stated minimal risk of flooding. But, in 2007, the maps were updating, putting the Arkema facility within 100- and 500-year flood zones. According to a report by the Chemical Safety Board, in spite of numerous sources showing that the facility was at risk of flooding, the facility employees were unaware of the risk and the facility was not required by federal regulations to consider flood maps or related studies as part of their risk assessment or emergency preparedness plans. The Arkema risk assessments did not include information on flood risk.

Who is impacted by chemical disasters?

The Arkema disaster was circulated widely as live television broadcast footage of the fires and smoke plumes. But not all chemical disasters make it to prime-time TV. Often, these events and their impacts on workers, first-responders, and communities happen more quietly or play out over time—and may go unnoticed by the media.

And these impacts do not affect everyone equally. As is often the case with chemical and industrial facilities, the communities living around RMP-regulated facilities are disproportionately low-income communities and people of color. Each day, these communities—sometimes surrounded on all sides by dangerous, polluting industrial facilities—are forced to live with threats to their health and well-being, often without the information they need to keep themselves and their families safe.

In other words, the issue of preventing chemical disasters is not only an issue of environmental impact and public health—it’s an issues of environmental justice.

Preventing double disasters

Currently, the RMP rule does not require facilities to have back-up power or air monitoring on site, nor does it require facilities to consider or address threats from natural disasters or climate change, nor does it require implementation of inherently safer technological or chemical alternatives in risk management plans —weaknesses that endanger facility workers and surrounding communities.

Recently, UCS partnered with the Center for Progressive Reform (CPR) and Earthjustice to assess the scale of this problem. In our resulting analysis, we identified nearly 4,000 RMP facilities in areas prone to natural disasters that will likely be exacerbated by climate change.

As climate change causes more frequent and intense natural disasters, our leaders in government must ensure that our regulations keep us safe from the fallout. We have the data and science to understand the risks; now, it is up to the EPA to use this science to protect public health.

Our recommendations

The EPA recently held a public comment period on the RMP rule. UCS, CPR, and Earthjustice submitted detailed comments outlining the risks posed to facilities and community members, and what must be done to protect public health and work toward environmental justice. We highlighted the need to integrate climate change into facility risk assessments, establish air monitoring around facilities to protect and inform communities about risks, and expand RMP coverage to more facilities. The United Steelworkers, United Auto Workers, retired generals, including Russel Honoré, and former Governor Christine Todd Whitman, Harris County Attorney Christian Menefee, and other fenceline community members and workers nationwide also urged EPA to strengthen the rules to finally prevent chemical disasters.

EPA must act urgently to update the RMP rule by following the science and making this program finally fulfill its disaster prevention objective. Our government must ensure that industrial facilities account for the risks of climate-related natural disasters—and a stronger RMP rule focused on prevention will better protect the families and communities forced to live alongside polluting facilities. As President Biden said, the climate crisis “is one of the great challenges of our time.” It is essential for Administrator Regan to heed that call and issue a strong new chemical disaster prevention rule that meets this challenge, before another Arkema-like disaster hits.