The news these days has rightly focused on the Supreme Court’s landmark decision on access to health care. But with scant media attention, Congress on June 26 sent a bill to the President that is just as important to the health and well-being of each and every American family, and the future of scientific integrity at the Food and Drug Administration.

The law—the FDA Safety and Innovation Act—won bipartisan support. But it is not a public interest victory. Instead, after many hours of painful negotiations, this bill was the best FDA bill—best in terms of what how the public benefits from it—that a Congress riven with dissent and driven by industry pressure could pass.

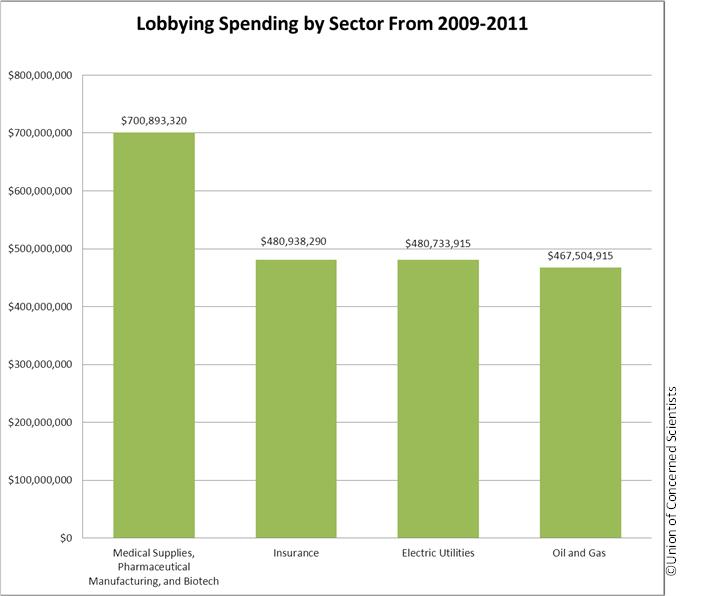

Every five years, Congress must pass an FDA law that approves user fee agreements that the FDA negotiates with the medical products industries. As we reported last March, these corporate interests had a lot of resources to make their case at the FDA and Congress. In the three years from 2009 through the end of 2011, the drug, device and biotech industries spent more than $700 million on lobbying at the federal level.

That buys a lot of influence, and that influence is reflected in the newly passed FDA law, which largely elevates speed over safety. It could have been much worse, were it not for the efforts of congressional leaders such as Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA), and Reps. Henry Waxman (D-CA), and Frank Pallone (D-NJ).

The law is not all bad. For the first time, for example, the FDA will have the resources from user fees to approve generic drugs and Congress has taken steps to address the problem of shortages of critically needed drugs. It now will be easier for the FDA to move devices approved under a less rigorous process to a classification meriting more surveillance. And the agency will have the power to halt a clinical trials of devices when they present “an unreasonable” safety risk to trial participants. Medical devices eventually will be able to be identified and tracked so that patients can be informed if there is a recall.

UCS, working with Public Citizen and other transparency groups, enlisted the aid of Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) to protect openness at the agency. The FDA had asked for the authority to keep a broad category of “drug-related” information secret, on the grounds that foreign governments and even domestic agencies would not share any information related to drugs if that information could be disclosed. The law, as passed, permits only limited restrictions on disclosure — when the agency needs sensitive information from foreign governments that only will be shared if kept confidential.

Increasing Corporate Influence over the FDA

Nevertheless, many of its provisions are a big wet kiss to deep-pocketed special interests, potentially eroding the independence of the agency and FDA scientists. For example, this law will eliminate limits on the number of experts who serve on FDA advisory panels who have financial ties to the makers of the very products that the panels will evaluate. Does that make sense to you?

In 2007, alarmed by the recall of Vioxx after it had been implicated in thousands of patient deaths, and other instances of lax scrutiny at the FDA, Congress opted to place some limits on the number of conflicted experts the FDA could use on its advisory panels. (UCS urged a total ban on conflicted experts, restricting their service to answering questions and making presentations.) But industry push-back against even this modest limit was massive. The FDA now will have no curbs on how many conflicted experts it uses.

At least progressive lawmakers were able to derail a proposal that would have denied the public from knowing when the FDA permits a conflicted expert to serve! Even disclosure had been on the congressional chopping block in the House.

The new law permits any device maker to challenge any significant FDA review decision and ask for it to be evaluated by a supervisor. This is particularly concerning because the user fee agreements stress adherence to industry priorities about keeping to a schedule, enhancing communication between companies and reviewers, and making the process work for them, not necessarily the patients the FDA is supposed to serve.

Congress also has imposed numerous new reporting burdens on the FDA, nearly all with the aim of micromanaging the agency and ensuring—do you see a theme here?—that it satisfies the demands of the drug, device and biotech industries.

We in the public interest world also think of the missed opportunities, what Congress could have done to protect scientific integrity and independence at the agency.

One omission that really hurts. More than 90 percent of devices are cleared (approved) because a company demonstrates that they are very similar to devices already on the market. Because of laws and regulations that favor the device industry, the FDA can do very little about the devices that came afterward that may have the same design defects, putting thousands of patients at risk. This new law will not change that.