Today, EPA finalized new standards for passenger cars and trucks for 2023-2026. This makes good on an early promise by the administration to roll back the previous administration’s rollback, and (importantly) the rule finalized today is stronger than what was proposed back in August.

By strengthening their proposal in 2025 and 2026, in particular, EPA is helping to put the auto industry back on track. While EPA left in place in 2023 and 2024 many of the credits that I previously flagged as loopholes, ending these “flexibilities” starting in 2025 dramatically improved the strength of the rule and sets the table to eliminate them entirely moving forward. As the agency gears up to go beyond 2026, a continued assurance that emission reductions tested in the lab yield real-world emissions reductions will help build toward the complete transition to electric vehicles by 2035 consistent with addressing climate change.

How the proposal was strengthened

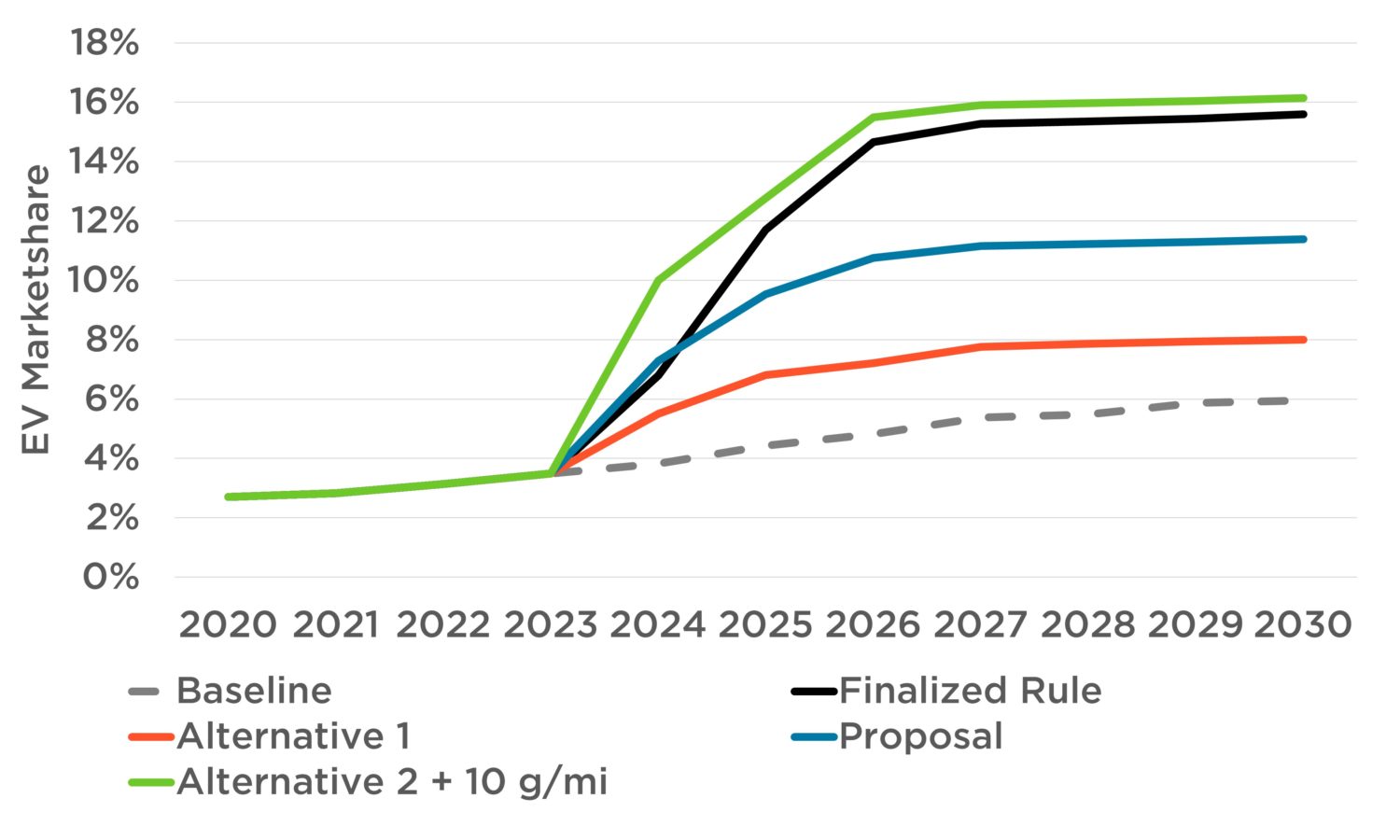

EPA’s proposal included a stronger alternative consistent with the original 2012 standards, so-called Alternative 2, which UCS advocated for based on our analysis of what is both achievable and necessary. This alternative also eliminated extra credits for hybrid pick-ups and electric vehicles. While EPA finalized a rule nearly identical to its proposal in model years 2023 and 2024, EPA adopted this stronger Alternative 2 for 2025. Even better, the agency adopted the target in 2026 that UCS advocated for, going beyond Alternative 2 by 10 g/mi. We estimate that the administration’s new proposal will reduce emissions by as much as 440 million metric tons over the lifetime of vehicles sold through 2026, an improvement of about 26 percent over the proposal.

Strengthening the rule in 2025 and 2026 will put a lot more pressure on automakers to ramp up the deployment of advanced combustion technologies and EVs. This is likely why the auto industry directly opposed increasing the stringency of the rule in 2026 and asked for greater loopholes, which would have created a rule more comparable to Alternative 1.

While the final rule may not fully adopt all of the changes UCS advocated for, EPA’s finalization of a stronger rule in the face of industry opposition will help set a course correction almost directly in line with what we know is achievable and is greatly strengthened compared to the administration’s original proposal. For example, we project that nearly half a million more EVs will be on the road in 2026 as a result of this increase in stringency.

EPA’s stronger rule includes reining in some of the credit loopholes the agency had originally proposed. Under the proposal, some of these loopholes could be used in model years 2021-2022, when the unjustifiably weak standards set under the previous administration are still in effect. This would have resulted in a windfall for manufacturers, but now the extra credits for hybrid pick-up trucks and electric vehicles have been narrowed to just a two-year window of availability (2023-2024). And the credit lifetime extension which has allowed industry to continue to kick the can down the road has been eliminated entirely.

Where we need to go next

While the administration strengthened its proposal and has helped course correct an industry that had pushed for rolling back these critical standards, we know that this is just the first step, and the next round of standards will be pivotal in achieving a more sustainable passenger vehicle fleet.

The next rule will presumably extend through at least 2030, per an Executive Order issued by President Biden that also “[set] a goal that 50 percent of all new passenger cars and light trucks sold in 2030 be zero-emission vehicles.” This is consistent with a recent National Academy of Sciences report and the trajectory called for by UCS, which targets 100 percent of new passenger cars and trucks be electric by 2035, in order to respond effectively to the climate crisis.

According to press releases, manufacturers claim to be preparing for a similar trajectory. The same day that President Biden announced his 2030 goal, a number of major automakers made commitments to similar levels of electrification by 2030, or of the companies’ aspirations to shift entirely to all-electric vehicles in the next two decades.

EPA’s next phase of regulations must provide the certainty needed to follow through on those promises.

What else can be done

A target for full electrification of the passenger vehicle market is an important framework for the next phase of regulation, but there are additional improvements that need to be made to the program. We’ve pointed out already the numerous credit loopholes that industry has pushed for to avoid real-world emissions reductions, and we will continue to press EPA to follow the evidence and eliminate any such manufacturer-requested loopholes.

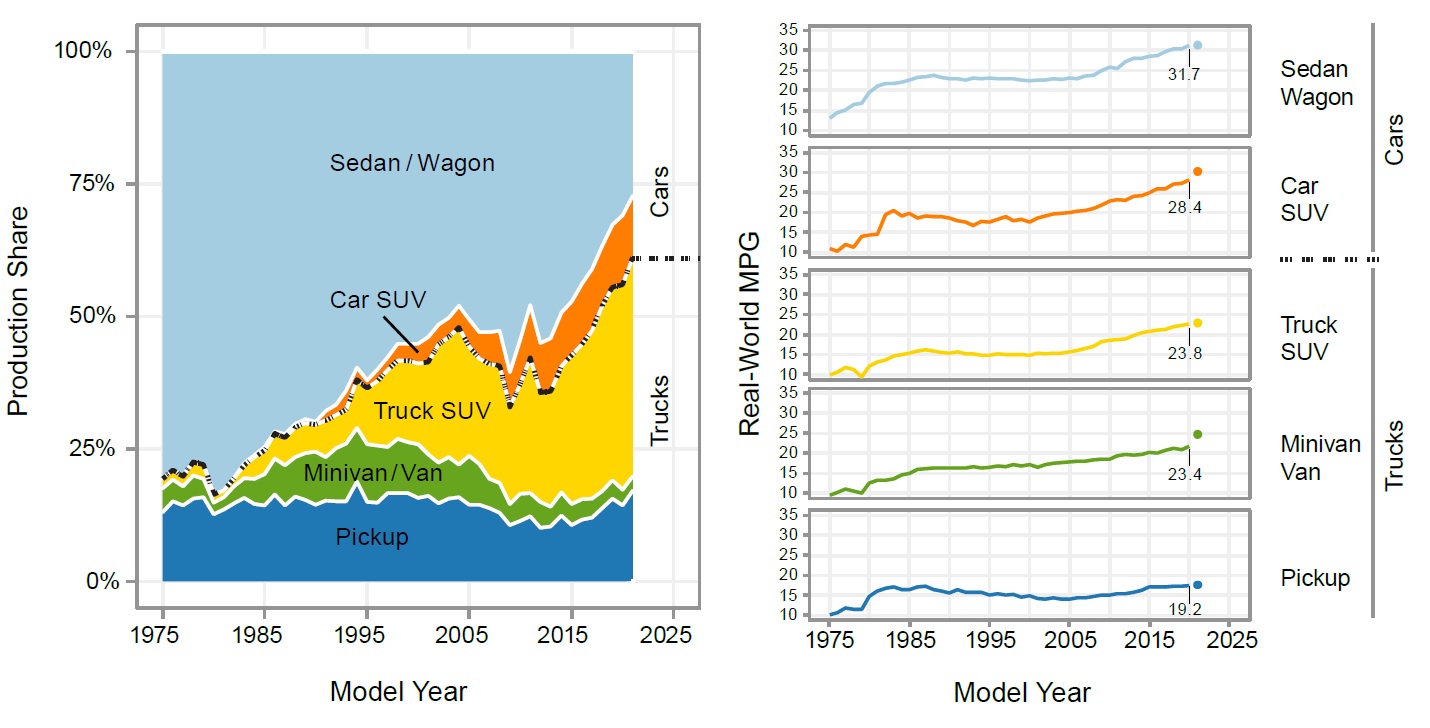

But EPA should think beyond minor tweaks to flexibilities and consider revisiting the structure of its current program in the next round of standards. The rules currently have different standards for different sizes of vehicles (larger vehicles have a weaker regulatory target). While these attribute-based standards mean that consumers have the most efficient choices ever, no matter the size or type of vehicle in which they’re interested, the lower standards for larger vehicles have been exploited by manufacturers. This has become a bigger issue as more SUVs are sold year-over-year than ever before.

Over the past decade, the average new vehicle has gotten about 12 percent more fuel-efficient. However, over that same time, the average vehicle has reduced zero-to-60 mph acceleration by 11 percent, gotten about 5 percent bigger (by vehicle footprint), and we’ve shifted from a marketshare of 45 percent for light trucks and SUVs to 70 percent. Those changes in fleet performance characteristics have cut reductions in fuel use and emissions about in half.

EPA must consider how the design of its standards can be improved to maximize fuel efficiency (and reduce emissions) of the total new light-duty vehicle fleet. One of the most obvious starting points is to start treating cars and SUVs equivalently.

New vehicle standards are not the only opportunity

As we push for stronger standards for new cars and trucks, we must also push for a broader package of solutions, if we are to effectively respond to the climate crisis. As we push for manufacturers to electrify their fleets, we also need to support equitable deployment of EV infrastructure and incentive policies that help ensure the communities that are most burdened by transportation pollution have access to the cleanest vehicles. And, importantly, we need to work to support more equitable access to public transit and other mobility solutions beyond personal vehicles, to reduce our dependency on cars for personal mobility and improve access to jobs for communities being pushed further and further from economic development. This is why we will continue to push Congress to pass the Build Back Better Act and advocate for systemic transportation and land use reform.

EPA’s step forward today improves the outlook for the new passenger vehicle market and consumers who can afford those vehicles. But this must be just one step of many from the Biden administration to make our transportation system more sustainable.

We will continue to push the administration to set strong standards that will ensure electric vehicle deployment in the new year. We appreciate EPA’s gift of significantly stronger standards going into our holiday break.