EPA just put out its annual report on the emissions and fuel use from passenger cars and trucks. The good news: vehicles are more efficient than ever before, with the average vehicle achieving 25.4 miles per gallon on-road and every class of vehicle at a record high. The downside to all this progress, however, is that the regulations have been so lax that manufacturers are at nowhere near the levels of efficiency originally envisioned by the program, and yet industry is sitting on a massive bank of credits that could continue to delay progress.

EPA is getting ready to finalize new 2023-2026 regulations—here’s what I’m hoping they take away from their own latest report.

Rules work (as designed)

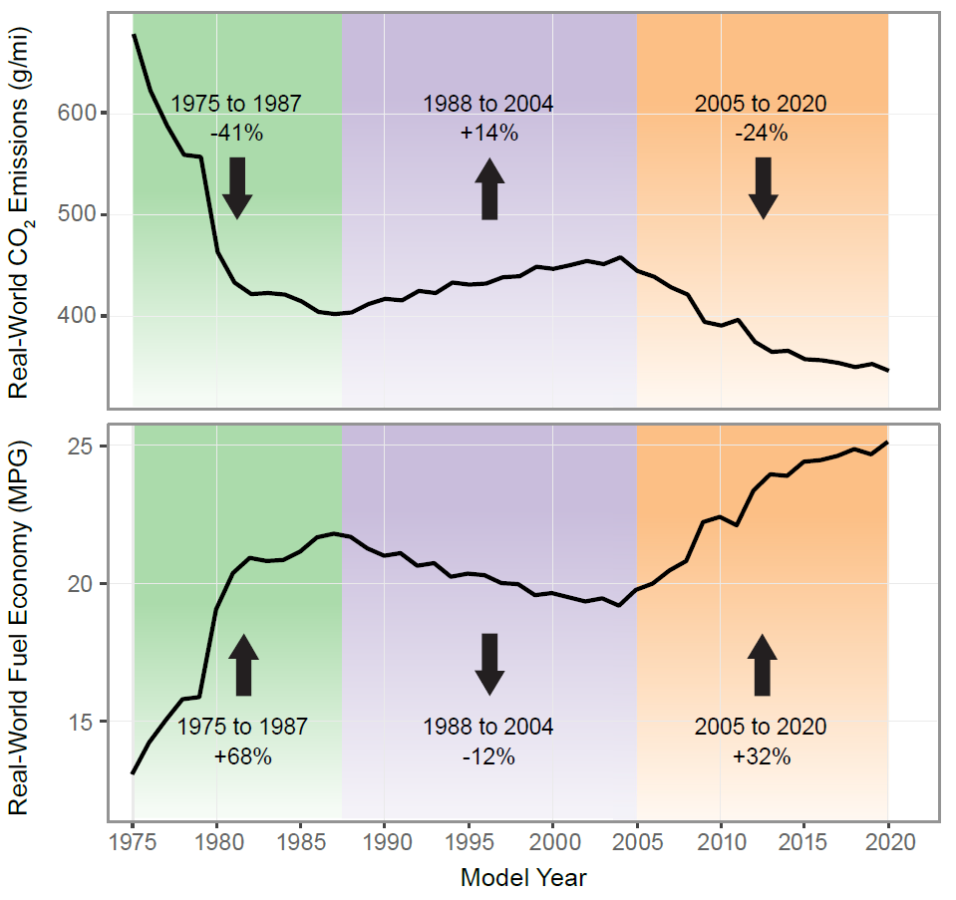

The first thing that EPA should recognize is that the rules are working, more or less as intended (more on that below). We are at record-high levels of fuel economy across the board, which is great for consumers no matter what type of vehicle they are looking for.

This is in strong contrast to the 1990s-early 2000s, when regulations were flat and fuel economy got worse. What changed? Standards got tougher.

To effectively address climate change, 100% of new passenger cars and trucks sold in 2035 should be electric. EPA has the power to make that happen, with binding regulations that work.

Gasoline-powered vehicles can do so much more

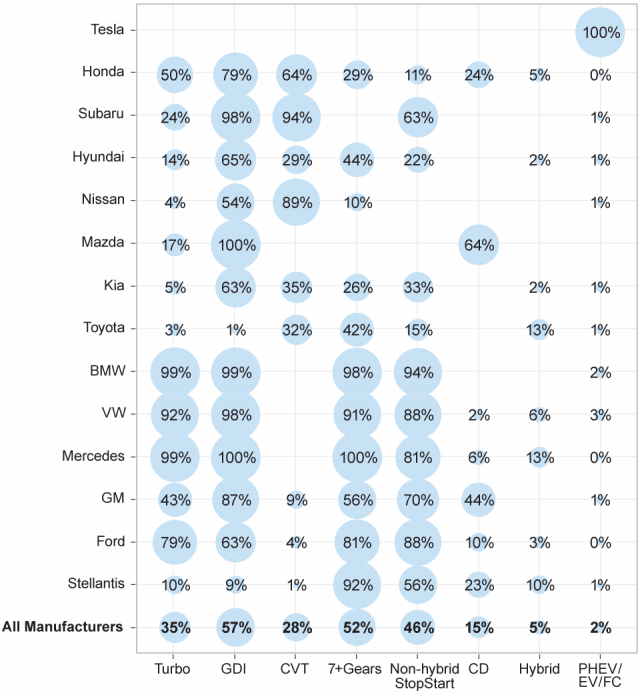

Long-term regulations need to be built on the electric vehicles that are both 1) needed to address climate change and 2) seeing major investments to scale up sales according to major manufacturers. But as we push that transition forward, more needs to be done to make the internal combustion engine more efficient. The vast majority of sales over the next decade are still going to be powered by gasoline—but EPA’s report shows there are still plenty of options on the table to reduce fuel consumption by those vehicles.

Manufacturers are nowhere near exhausting even the most obvious, off-the-shelf engine technologies. Barely half of engines are even using direct injection, less than half have some form of stop-start/hybridization to reduce idle fuel waste, and an extremely small share of the fleet is taking advantage of cylinder deactivation, which can “right size” an engine in real-time to maximize its efficiency.

On top of these long-known strategies that have yet to be made ubiquitous, there are plenty of continued incremental advancements like new high-energy ignition systems that replace the conventional spark plug with more efficient burn strategies.

EPA should look at its data on technology deployment to-date and conclude that its rules can push much further, and fast.

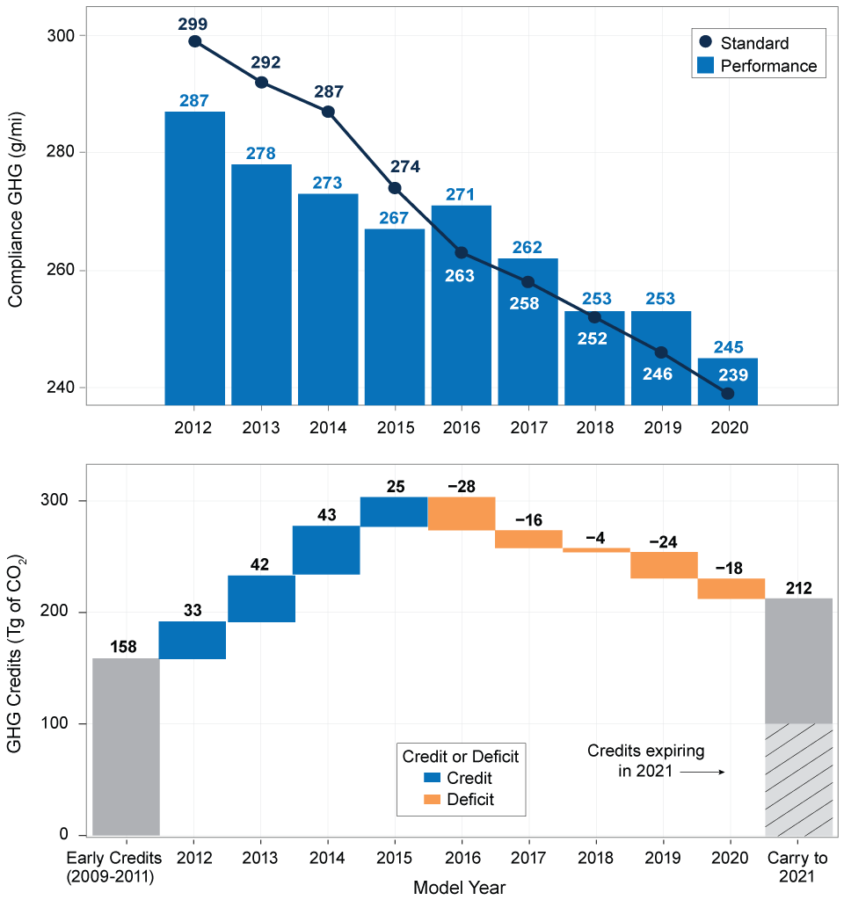

A glut of credits continues to make compliance way too easy

Sadly, one of the clearest things that EPA should learn from this latest report is why its current regulations aren’t doing enough to drive innovation in the industry. The industry is sitting on a glut of credits that can be used in lieu of technology deployment, and manufacturers are doing just that.

In the near-term, EPA can point to this massive bank of credits as a clear reason why the industry is well-prepared for a steep increase in standards for 2023. But in the long run, EPA needs to focus on ensuring that its standards have much less wiggle room and are built not on massive credit giveaways but real reductions in global warming emissions.

Now is not the time to be timid

Regulations have pushed manufacturers to offer the most efficient vehicles ever, year after year. But there is still so much more that can and must be done to address climate change.

EPA’s latest report shows the successes of its program, but the data also points to an opportunity for significantly tightening the stringency of the program in the 2023-2026 period as industry transitions from the weak regulations of the previous administration towards what is necessary to address climate change. This becomes even more critical for the transportation sector, now the largest source of global warming emissions in the United States, particularly given the failure of COP26 to meaningfully prioritize transitioning away from fossil fuels.

The science clearly indicated that EPA’s proposal was far too weak, and its latest report on the state of the industry only furthers that evidence. Regulations can work to make industry do better, but we must make the regulations work better if we want industry to address climate change.

EPA Administrator Regan said that the agency will “follow the law, follow the science and build the strongest technical record” and will finalize the rule accordingly. Well, the data is clear—we can and must do more, not just through 2026 but beyond.