It has been over twenty years since smog-forming and particulate pollution standards for heavy-duty trucks were strengthened. In the absence of federal action, states have moved forward to reduce pollution from trucks. Unfortunately, just last week truck manufacturers filed a lawsuit to prevent states from enforcing these more protective standards. And as EPA moves forward with its own proposal to finally strengthen truck pollution regulations, industry has been waging an all-out war on those, too.

This fight by industry to delay, obstruct, and otherwise thwart stronger regulation has devastating consequences. To push EPA to institute standards that live up to its authority under the Clean Air Act and protect public health, the Union of Concerned Scientists submitted technical comments to EPA on its truck rule, as a member of the Moving Forward Network (MFN), a national network of organizations that center grassroots, frontline knowledge, expertise, and engagement with the communities across the United States that bear the negative impacts from the global freight transportation system, including heavy-duty trucks.

There are grave concerns we at UCS have about this rule, and nearly 1,000 health professionals, scientists, and engineers in our Science Network agreed that this NOX rule should be strengthened to live up to the agency’s explicit commitments to climate, clean air, and environmental justice. Below I dig into a little bit more about what is actually in the proposal, and why it is so insufficient to tackle the widespread environmental harms that face freight-impacted communities.

Justice delayed Is justice denied

In thinking about EPA’s proposal, I think it’s critical to center something Angelo Logan, policy and campaign director for the Moving Forward Network, has continually reminded me about: “Justice delayed is justice denied.” This is not some pithy slogan—it is a reminder that every delay in action means another day that local communities are inundated with freight pollution, an injustice that stems from the racial bias that has run the core of commercial freight through communities of color.

I went into some detail about the high-level options proposed by the agency in my previous blog, but the summary is that it appeared that EPA had proposed either eventually (in 2031) aligning with state standards, or alternatively moving to merely adopt industry’s proposed standards.

Neither of these outcomes is sufficient to deal with the problems facing communities today, and as detailed below the rule does absolutely nothing to push deployment of the solution those communities have asked for, which is eliminating tailpipe pollution entirely. But after digging deeper into the rule, it’s even worse than I originally thought.

EPA’s backdoor proposal to giving industry what it wants

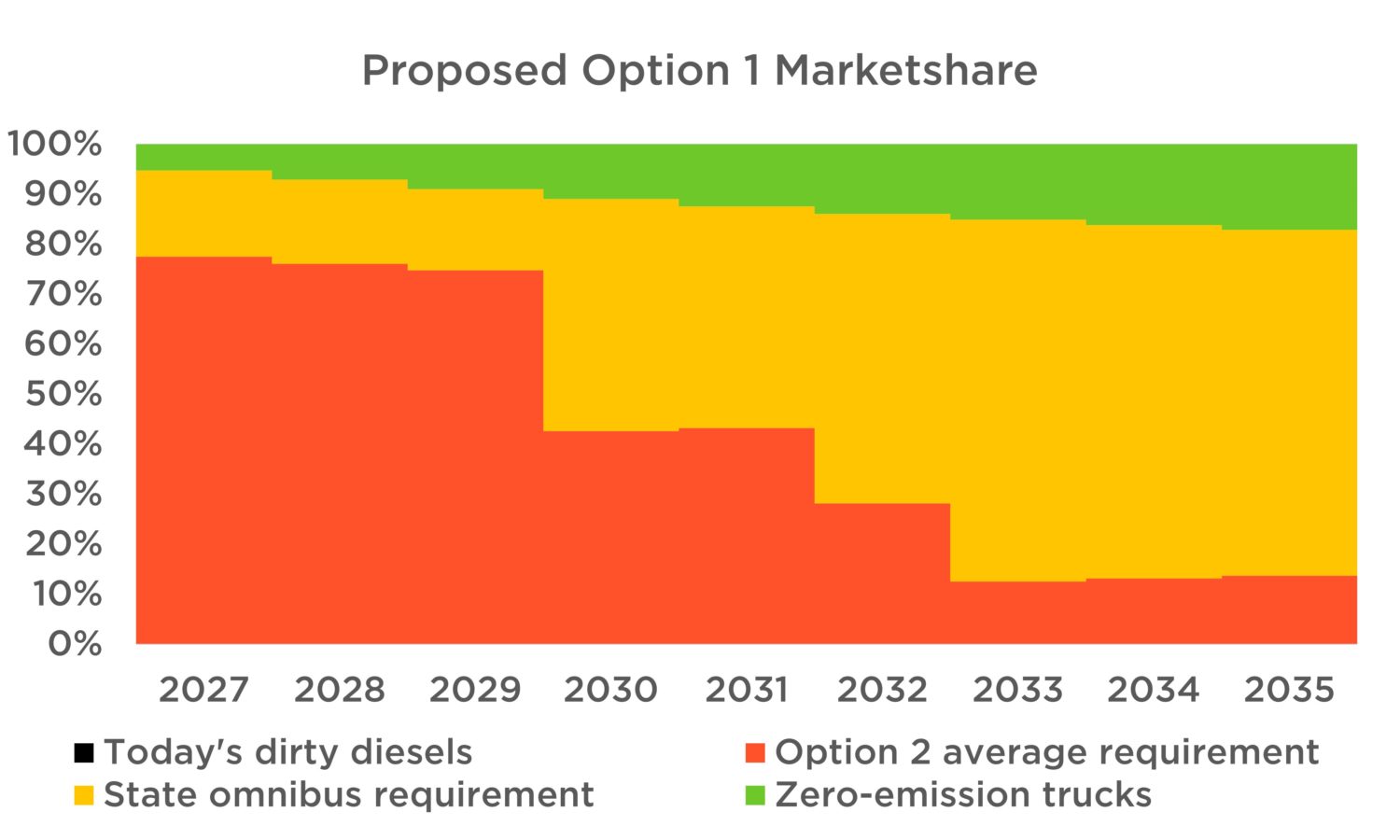

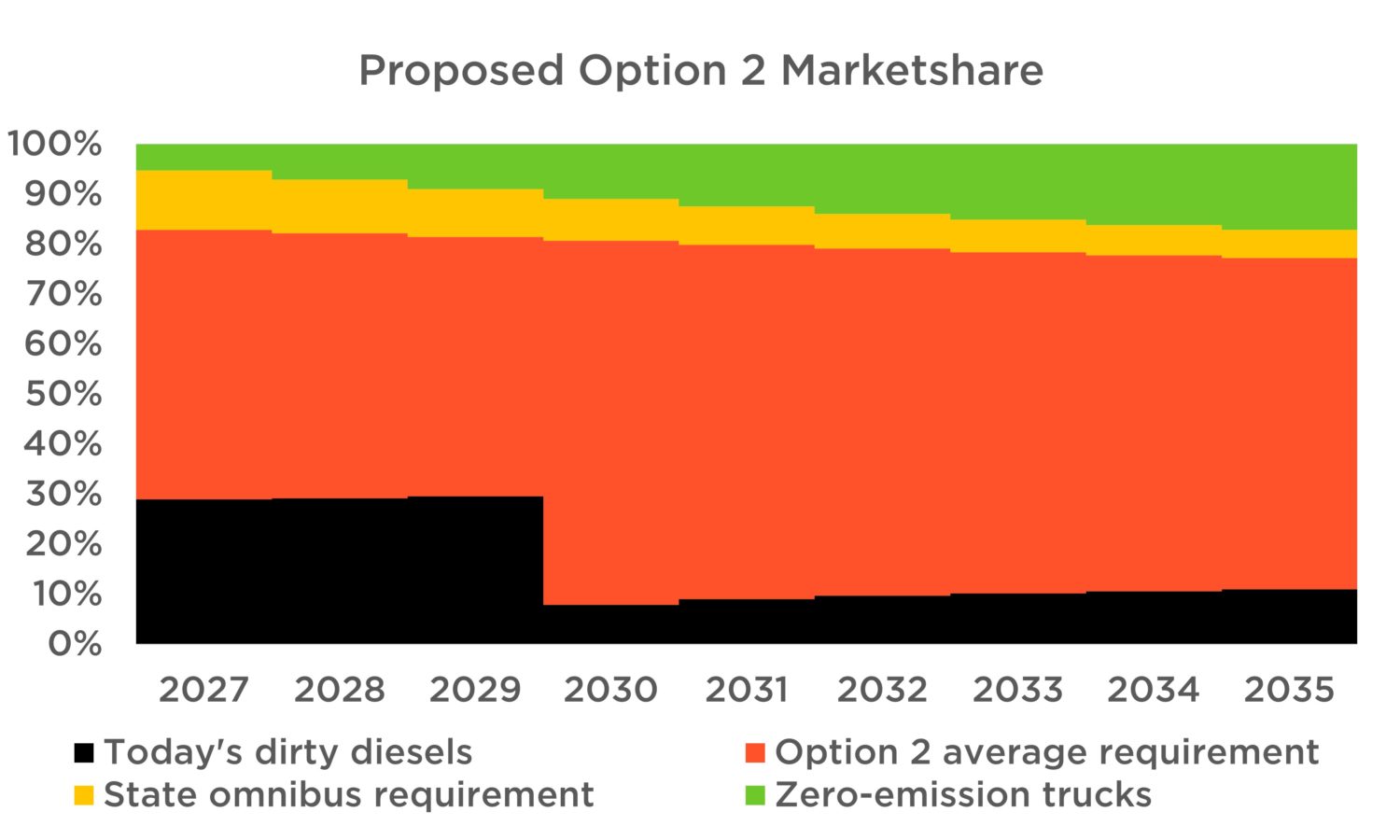

It turns out that EPA has packed the proposal with credit giveaways. I’ve commented on this type of nonsense before in the passenger vehicle market, where EPA loopholes gave away 16 percent of the benefits that the rules were supposed to deliver. This truck proposal is just more of the same: when considering credits, Option 1 gives away 12 percent of the first step of regulations (2027-2030), causing even further delayed action in an industry that hasn’t seen new tailpipe NOX regulation in over 20 years.

EPA is giving away credits for a number of things that are already happening, credits that can then be used to offset shortfalls in emissions performance under the new, stronger standards, thanks to the averaging, banking, and trading provisions of the heavy-duty truck rule. EPA hasn’t even bothered to consider the availability of these credits in setting the standards, allowing manufacturers to earn credits for things they were already going to be doing that they will then cash in to avoid meeting the stronger emissions requirements down the road.

Three massive credit giveaways for the status quo particularly undermine the current rules: under a new proposed “Transitional Credit” program they will be able to earn credits for performing better than the current, weak standards—something manufacturers are already doing; engines sold under state standards exceed the strongest standards proposed by EPA in 2024-2030 and will earn credits both under the transitional program and the general banking and trading provisions; and all electric trucks sold beginning in 2024, including those required under the Advanced Clean Trucks rules adopted by six states, will earn credits.

The net impact of these windfall credits awarded for status quo deployment is bonkers. As shown below, if EPA finalized Option 1, manufacturers wouldn’t really have to do any better than Option 2’s targets for the first 3 years. And if EPA finalized Option 2, nearly 30 percent of trucks sold 2027-2029 could be no better than today’s best-forming (but still dirty) diesel trucks! On top of two decades of inaction, it’s hard to understand EPA’s thought process here to further delay progress.

Act now—drive emissions reductions a.s.a.p.

Communities have been clear: a zero-emissions freight system is required to reach environmental justice. Truck traffic has been on the rise, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that increase means even more air pollution in communities already disproportionately impacted by the public health emergency. The only equitable solution to such impacts is to eliminate the problem in those communities, and that means eliminating tailpipe emissions as quickly as possible.

Instead of addressing the problem head-on, EPA’s proposal kicks the can down the road. In contrast to what we and others have been advocating for, EPA did not propose to set sales targets for electric trucks. Major truck manufacturers like Volvo/Mack and Navistar/International claim that they are already planning for up to 50 percent of truck sales to be electric by 2030, yet EPA is not holding their feet to the fire and requiring such committed action.

In fact, EPA’s proposal does not require any action whatsoever on electric trucks. While the agency proposes to give credit to such trucks, acknowledging “the zero-tailpipe emissions performance of these technologies,” they have not set any targets based on this performance. The result of that is the erosion described above.

EPA choosing to ignore the best available technology to reduce emissions is, plainly, against the Clean Air Act, which states that trucks standards must “reflect the greatest degree of emission reduction achievable through the application of technology which the Administrator determines will be available for the model year to which such standards apply.”

Extensive testing by EPA and suppliers like Eaton and Achates shows that diesels can achieve a 20 mg NOX/bhp-hr standard. Truck manufacturers say they are targeting 50 percent electric truck sales by 2030. If EPA wants to set an average NOX standard consistent with those simple facts to drive the maximum emissions reductions from diesels while maximizing zero-emission sales, it’s elementary school math to realize you need to set a standard below 20 mg/bhp-hr!

In other words, if EPA wants to drive zero-emission trucks to market, it has to do a heckuva lot better than Option 1. And there’s no time to waste.

Not waiting for industry to get their way

The pollution from the trucking industry is too big a problem to just sit around and wait for EPA to make up its mind—communities of color around the country are disproportionately exposed to heavy-duty pollution, and that disparity continues to persist nationwide as a result of racist housing policy and other factors. If EPA is serious about confronting environmental justice, cleaning up the freight sector must become a priority—thus far, that has not been the case.

While we pressed our case to the agency via joint technical comments, we will continue to engage the agency and present to them the best available data, including refuting the bogus industry talking points we’ve already seen trickle into the docket. It’s clear that the trucking industry is aiming to continue its practice of not paying for its tremendous social harms—communities nationwide cannot continue to bear such injustice. Thousands of UCS supporters have already stood up to make their voices heard in this fight, and we will continue to channel that energy in pressuring the agency to do what the science shows is clearly feasible to address these longstanding harms.