My last two blogs have focused on some of the regulatory loopholes that automakers have pushed for to weaken standards. However, the harm from these loopholes is compounded by the way in which credits are earned and used under the current fuel economy and emissions rules.

The Biden administration should learn from the shortcomings of the current regulations in order to push the industry forward. Under the current structure, there are innumerable instances of automakers exploiting the program to delay climate action. EPA needn’t be, and frankly can’t be, so forgiving in its next rulemaking.

How credits are supposed to work

Cars and trucks are not like cell phones, that come out with a new and drastically different product every year or two. Instead, a typical car or truck goes at least five years between major redesigns, with only minor changes usually made in the intervening years. Generally, it is in the full product redesign when the biggest changes can be made to improve fuel economy and emissions, whether that’s a new lightweight frame, improvements to aerodynamic drag, or completely new engine and transmission options. This long lifecycle creates complexity for fuel economy and emissions programs, which are implemented on an annual basis.

To overcome this “stepped” design process, regulations have averaging, banking, and trading (ABT) provisions designed to offer manufacturers flexibility. Averaging means that a manufacturer is judged on the sales-weighted average of its entire fleet—this gives manufacturers the ability to have low-volume high-performance models, or to ensure that changes to an individual model or fluctuations in its sales volume in a given year cannot by itself substantially change compliance. Banking helps balance out changes over a model’s product cycle—when a new vehicle is released, it will typically have above-average efficiency, which means it can generate credits, which are then banked by the manufacturer; as the model ages, and the regulations get harder, the manufacturer can then use those banked credits to balance out the shortcomings until the next redesign. And finally, trading allows for manufacturers to trade credits with other manufacturers, in order to further balance out large credit banks or deficits in a given year.

The purpose of the ABT program is to smooth out the fluctuations that naturally happen in the automotive industry—unfortunately, lately it’s been used to delay action.

Getting credit for doing nothing

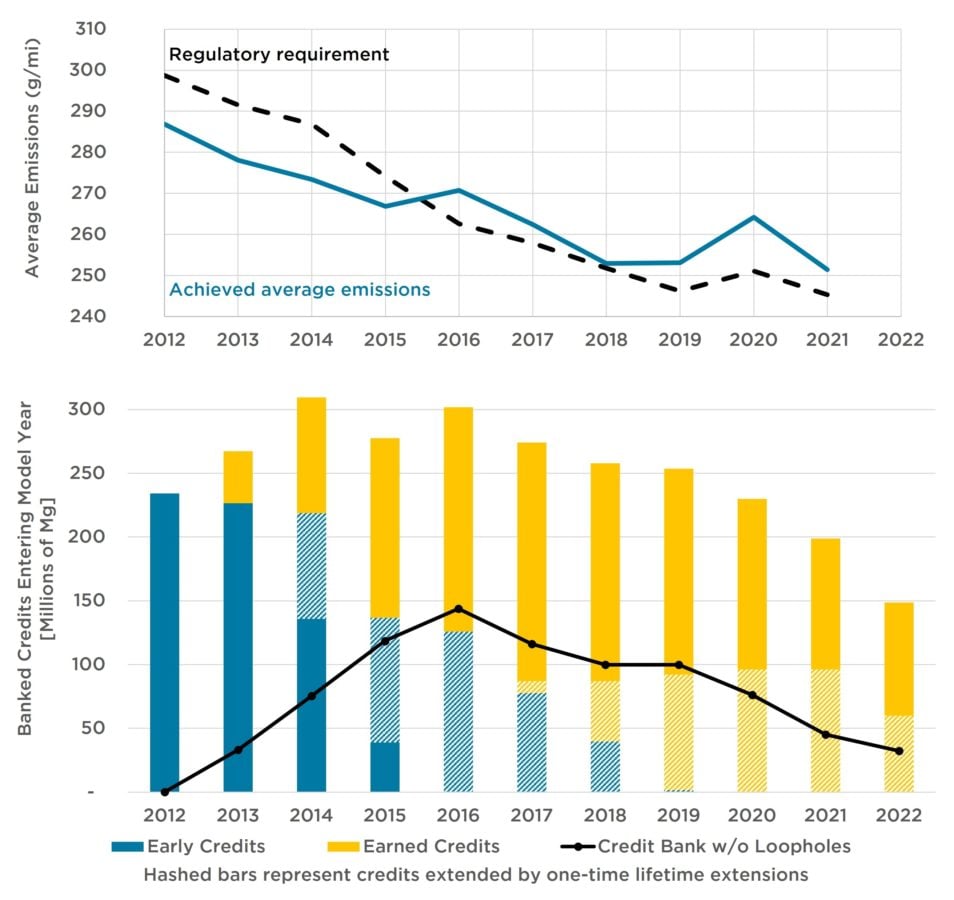

In 2010, EPA finalized its first global warming emissions standards, scheduled to start with the 2012 model year. In keeping with the existing ABT program used by the Department of Transportation’s fuel economy program (CAFE), they decided to allow manufacturers a head-start on their credit banks, with an “early credits” program for model years 2009-2011. This program was meant to act as a bridge between manufacturer progress on state emissions standards and national fuel economy standards, and the federal emissions standards being put in effect in 2012. However, the actual net effect of the program was to create a double-dip crediting scheme that delayed progress significantly.

One critical issue is that EPA underestimated the performance of the status quo. I mentioned this in the off-cycle credit blog, but it holds true overall: EPA staff did not fully consider the technology already available on the fleet, particularly with air-conditioning and off-cycle improvements not already considered under CAFE. This effectively led to a double-dip credit windfall for manufacturers: first, EPA set a standard that was less stringent than what vehicles on the market were capable of achieving; then, under the “early credit” program, manufacturers got extra credit for these technologies, even though they added nothing to their vehicles to earn them.

The early credit bank allowed manufacturers to bank and utilize 56 million credits which would have otherwise been needed for compliance due to shortfalls in the fleet. These unearned credits have been used to avoid future vehicle improvements.

Using credits to do nothing

The head-start given to manufacturers significantly diminished the need to improve their vehicles in the early years of the EPA program. However, this delay in action was made even worse by yet another gift to the auto industry: a one-time credit lifetime extension.

Normally, the lifetime of emissions credits are five years, comparable to the automotive product cycle. However, under the credit lifetime extension, credits earned in model years 2010-2015 could be used all the way through 2021. (Mind you, there were no EPA standards in 2010 and 2011, so those are all early credits.) The agency claimed extending the credit lifetime in this way “allows additional flexibility, encourages earlier penetration of emission reduction technologies sooner than might otherwise occur, and does so without reducing the overall effectiveness of the program.” However, they were wrong.

The majority of early credits should have expired, limiting the damage of the credit bonanza EPA gave away at the start of the program. Unfortunately, the agency’s decision to grant a one-time extension allowed 60 million credits to stick around beyond their expiration, further diminishing the stringency of the program.

The data speaks quite clearly to the impact of this credit extension: right when the program was meant to be more binding and spur technology advancement, manufacturers actually did less because they had amassed a tremendous credit bank. This is perhaps most clear when looking at a company like Toyota—Toyota amassed the largest number of early credits, and its light truck fleet has been running a deficit since 2012, largely because they neglected to make major improvements to an engine platform used throughout its light truck fleet. Toyota has used its large credit bank to offset these deficits, and they have so many credits left over that they have recently been selling them to companies like Stellantis (fka Fiat-Chrysler) and Mercedes, who have relied on such credits for compliance for nearly the entire time this program has been in place rather than take the step of selling efficient vehicles as required.

The cost of doing nothing

The impact of this delay is significant. By allowing automakers to comply with credits banked for doing absolutely nothing, EPA reduced the incentive for the companies to deploy even the technologies they had right off the shelf. On top of that, these same companies then tried to use their own decisions not to make more efficient vehicles in their petition for a rollback, which was granted and set us even further back. And finally, the result of this is to inflate the credits available for more stringent standards in the future, continuing their ability to kick the can down the road.

| Loophole | Real-world emissions impact [millions of metric tons] |

|---|---|

| Air-conditioning and off-cycle credits | |

| Off-cycle credits not matched by real-world data | 59 |

| Alternative fueled vehicles | |

| Excess flex-fuel vehicle sales | 54 |

| Electric vehicle incentives (multipliers, 0 g/mi) | 139 |

| Credit banking giveaways | |

| Extended credit lifetime | 100 |

| Early credits | 94 |

| Real-world benefits of standards (2011-2021) | 2,420 |

| Total foregone benefits from loopholes | 446 |

| Loophole cost: | -16% |

We added up the harms of the various loopholes and credit flexibilities, and it’s staggering. Make no mistake—the rules have been tremendously successful overall, cutting global warming emissions by 2.4 billion tons over the lifetimes of vehicles sold from 2012-2021. But an additional 450 million tons of benefits were lost as a result of these handouts, equivalent to 5 billion barrels of oil.

No more delays

The Biden administration is getting ready to propose new vehicle standards through model year 2026, the first in what will hopefully be a multi-step process towards getting us back on track with our climate goals, with longer-term standards for 2030 and beyond needing to set the industry up for a fully electrified future.

This first step is critical and sends a signal about future action. Is the administration going to be bold, rebounding to standards at least as strong as the Obama administration first finalized nearly a decade ago? Or are they going to continue this history of finalizing loopholes requested by industry that undermine the standards?

We’ve learned that the strength of a rule is not about top-line numbers—it’s about climate impacts. And with the forthcoming proposal, we’ll get a solid glimpse of how seriously this administration is committed to addressing climate change from transportation. More loopholes are not going to cut it.